Coming Clean: Amid Opioid Devastation, Industry and Regulators Scour for Solutions

Our March 2018 coverage of the opioid crisis recently became a finalist for a "Best Single Article" Neal Award. The Neal Awards are considered the most prestigious honors in specialized journalism, and are given for content that brings attention to critical new trends on important topics with "brilliant tactics and innovative leadership." We couldn't be more honored to be included in the list of finalists. Winners will be announced March 29, 2019.

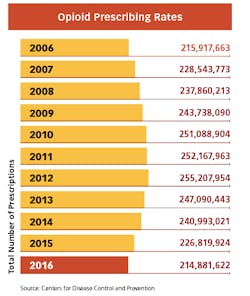

A day rarely goes by without opioids making headlines in the national news. With overdoses still at staggering highs (the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 115 Americans die every day from opioid overdose), it has become one of the most devastating health problems in U.S. history.

Recently, however, the front lines have shifted from the doctor’s office to the streets as illicit fentanyl — a potent opioid that’s often made in China and smuggled into the U.S. — becomes the prime source of overdose and death.

But that doesn’t mean the pharmaceutical industry is done grappling with this crisis. In fact, by many measures, the legal, regulatory and market fallout has just begun.and smuggled into the U.S. — becomes the prime source of overdose and death.

Years ago, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration took calculated steps to address the situation. Now, the agency is in a full-on gallop towards the goals of preventing addiction, curbing abuse, and expanding treatment for opioid addicts — all while attempting to protect the needs of chronic pain patients.

Meanwhile, several key industry players have launched other programs to help — from educating healthcare professionals about prescribing opioids to adjusting formulations to deter abuse. R&D teams have also sprung into action to develop alternative painkillers or new opioid medications that carry fewer addiction risks. Dozens of new drugs to treat pain and addiction are also on the horizon and could soon be in reach.

While opioid lawsuits continue to play out in the legal system, outside the courtrooms, focus has shifted towards mitigation strategies, as regulators, manufacturers and researchers help pick up the pieces of the opioid storm.

The Blame Game Continues in the Courts

The history of the rising prescription rates for narcotics and addiction have been well documented, and despite the changing patterns of drug abuse, pharmaceutical companies are still taking the brunt of the blame. The American legal system is fast becoming the main theater for the ongoing drama.

What began as a handful of local governments suing major opioid manufacturers such as Purdue Pharma and Johnson & Johnson a few years ago, has turned into an avalanche of litigation. Currently, drugmakers and distributors are staring down more than 250 lawsuits from states, counties and even hospitals.

More than a decade ago, executives from Purdue pleaded guilty to charges that they misled the public about Oxycontin’s risks and agreed to pay $634 million in fines that were divvied up between private parties, and state and federal agencies.

But Purdue has also netted about $35 billion in sales from Oxycontin since it began marketing the drug in 1996, and many of the plaintiffs claim that the company hasn’t paid its fair share for the medication’s impact.

The company is certainly facing a mountain of legal costs now and finds itself in a tricky conundrum: If Purdue settles any cases, it could lead others to sue. For this reason, the company is reportedly hoping instead for a global settlement — similar to the settlement that was made with tobacco companies in 1998. A U.S. district judge in Cleveland reportedly has the same goal, and has been in talks with manufacturers and various agencies about coming to an agreement before all of the parties involved become entangled in years of costly litigation.

Critics point out that manufacturers may not be willing to pay a sum even close to the estimated $500 billion a year opioid addiction costs the country. Pharma companies could also make a strong case that they shouldn’t be forced to financially compensate for addiction now that the epidemic is more closely linked to street drugs.

Because these talks just began this winter, it remains to be seen if manufacturers will walk away with a settlement deal or be stuck in the long, legal shadow Oxycontin has cast for years to come.

The Industry ResponseLike many industries, the pharma world has never been without some controversies. And after any disaster, there’s always a period of introspection when the dust settles, the damage is assessed and the hard lessons are learned, so that mistakes won’t be repeated.

In the case of opioids and other potentially addictive medications, the tone of the conversation throughout the industry has taken a dramatic shift in recent years according to Ed Elder, the director of the Lenor Zeeh Pharmaceutical Experiment Station and a professor at the UW-Madison School of Pharmacy.

“For a long time, the industry focus was on providing the benefit [of painkillers] and not mitigating the risk,” he says. “Now there’s a been a lot more focus on...finding mitigation strategies to address that.”

Even though many in the industry have been accused of causing the epidemic, they are now stepping up to show they have some of the best solutions, too.

Among the dozens of opioid manufacturers in the U.S, you’d be hard pressed to find one that has taken more of a leading role on that front than Purdue. So far, Purdue has expressed support for limiting the length of first opioid prescriptions, the use of prescription monitoring programs, switching to abuse-deterrent formulations for opioids and most recently, promised to stop its sales force from touting the benefits of opioids to doctors.

The industry’s biggest lobbying arm, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), has also taken a leading role in the issue. Late last year, PhRMA announced that it is embarking on a multi-year, multimillion dollar initiative to address the opioid crisis that includes a partnership with the Addiction Policy Forum. The effort will funnel money toward state and local programs for addiction treatment and help families impacted by opioids.

PhRMA has also joined forces with the National Institutes of Health to accelerate research toward non-addictive pain medications and new treatments for addiction, and is an outspoken supporter of limiting initial prescriptions for narcotics, while protecting patient access to medically necessary painkillers.

“The industry has taken substantial steps forward on the issue,” says Nick McGee, director of public affairs at PhRMA. “Because it is a broad and complex issue, it’s going to take all relevant stakeholders to help solve the problem. Our goal is to be a part of that comprehensive solution.”

The FDA recently began taking a myriad of new steps to tighten controls around narcotics. Last fall, the agency notified 74 manufacturers that it is expanding rules that previously only effected extended release (ER) opioids to immediate release (IR) painkillers as well.

Currently 90 percent of all prescribed painkillers are IR and are many people’s first exposure to narcotics. The new requirements mandated under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) will require manufacturers to provide training to healthcare professionals about safe prescribing practices for IR opioids and prompt them to consider alternatives.

“For the first time, this training will also be made available to other healthcare professionals who are involved in the management of patients with pain, including nurses and pharmacists, which is in addition to prescribers,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said in a statement about the change.

All told, the existing REMS, which already impact 64 ER formulations, will now include an additional 277 IR medications.

The agency is also considering a new rule that would mandate that certain IR opioids come in blister packs of possibly two-or six-day supplies, so that prescribers are encouraged to dispense them for smaller durations of use.

So far, the FDA has been conducting stakeholder meetings about the potential change and hasn’t issued any final word on what the new regulation would require. Gottlieb admitted last year in an interview with CNBC that the changes could be “uncomfortable” for drugmakers because they would increase manufacturing costs.

Earlier this year, the FDA took a more direct step with manufacturers of loperamide, an anti-diarrhea drug, when it asked them to voluntarily change how the drug is packaged and sold. Because loperamide, sold under the brand name Imodium, can induce a mild opioid-like high in large quantities, a growing number of people have been abusing the drug in recent months, and at least a few have died. Although the FDA stopped short of mandating changes, the agency asked that manufacturers switch to blister packs and that distributers who sell the drug in bulk limit quantities available in an individual package.

On top of these targeted changes, the FDA has also rolled out its own comprehensive plan to combat opioid abuse, including the creation of a policy steering committee and a plan to fast-track approvals for new addiction treatments and non-opioid analgesics — which is fast becoming another pressing issue in the midst of the epidemic.

Whenever the FDA posts proposals for more stringent measures on opioids on the Federal Register, the comments from hundreds of pain patients pour in. While the regulatory focus is still on limiting pills from the doctor’s office — and the measures have already begun to make a dent in America’s prescribing rates — many believe it is becoming too difficult to get relief for legitimate pain. And many patients with chronic conditions are now being weaned off of the medications that have given them the ability to function in everyday life.

As the healthcare world turns away from narcotics, it is now turning to pharmaceutical companies to offer up new ways to treat pain.

The R&D FixAccording to PhRMA, there are about 40 new medications in the development pipeline for treating addiction and at least 40 new analgesics in the works as well.

One of the most promising fronts for offering pain relief while bypassing the euphoric side effects that can get patients hooked include drugs that target specific pain receptors instead of the central nervous system.

“The industry has accomplished this in other therapeutic areas, like treating cardiovascular disease,” Elder says. “Applying those concepts is an exciting way to go.”

One such non-opioid medication that’s generated a lot of buzz is tanezumab, which is being developed by Pfizer Inc. and Eli Lilly and Company. Designed to treat low back pain and osteoarthritis — two of the biggest prizes in the chronic pain market — the drug works by selectively targeting, binding to and blocking nerve growth factor. The FDA has given the medication fast track designation and it is currently in phase 3 clinical trials.

On the pre-clinical side, research teams have been getting inspiration from nature to develop drugs from exotic sources. One group at the University of Utah received a $10 million grant last year to study a kind of cone snail that uses a harpoon-like tooth to stab its prey and shoot them with a paralyzing venom. The team hopes to identify the compounds in the venom that contain pain-relieving properties and turn them into medications.

Another field of research that’s cropped up involves genes that impact the sodium channel NaV1.7, which controls pain signals to peripheral nerve cells while avoiding signals that travel to the brain. Several companies such as Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer have explored the sodium channel angle and then abandoned the quest after disappointing results. But a slew of other companies including Amgen, Roche and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals are still in the hunt for success and have various medications in early clinical trials.

Meanwhile, scientists are also looking at using existing technologies to make a new class of opioids that don’t have side effects such as respiratory depression and rising tolerance, which can lead to increased use.

Although it could be years before these new treatments make it to market, pharma companies are stepping up to fill the rising need for new pain-relieving treatments.

Bottom Line?

The opioid epidemic has become a watershed event for the pharmaceutical industry that will leave a lasting mark for years to come. As new regulations take shape that could impact a slew of medications, pharma companies throughout the supply chain would be wise to take proactive steps to mitigate addictions risks for users and find ways to be a part of the solution.

Recently at the AAM Access! 2018 Annual Meeting, the director of global policy at Walmart, Betsy Hall Collins, echoed these sentiments during a presentation about the impact of opioids on the pharma world. The retail giant announced this year that it will give away free packets of DisposeRX, which can be used to dispose of old medications, to customers receiving an opioid prescription.

“It’s best to find solutions now that work for your business, before someone is mandating solutions for you,” she said.