Pharmaceutical manufacturing professionals today can depend on one thing: constant change. Corporate focus may change to a new product or a new delivery method, and Lean Six Sigma programs may change established ways of doing things. There may be changes following a merger, or a shift to new materials and equipment.

Many drug companies don’t keep track of the number of document control or quality assurance changes they make. At the typical pharmaceutical facility, depending on type and size, changes can range from about 30 to 160 per month.

All this change must be managed if its randomness is to be removed. The goal of formal Management of Change (MOC) programs is to develop an approach that will require the least expenditure of time, effort and money.

First, a basic requirement and strategy must be established. Unfortunately, many QA managers at pharmaceutical companies are not familiar with MOC and some do not understand Quality Control, as the term has evolved in other industries. Often the emphasis is on firefighting and crisis management.

In one case, a drug manufacturer had finished product that could not be shipped. Analysis traced the problem to lack of change control in batch records. Changes never caught up with training or SOPs.

FDA has yet to issue a guidance document on change management. However, the U.S. Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) offers a useful model for pharma companies that can be applied broadly to managing change. This article will outline some useful best practices. This MOC model, OSHA regulation 29 CFR 1910.119, Process Safety Management, requires that any changes that affect a process be managed. Among its requirements:

- Establishing written procedures and documentation for all changes

- Documenting the purpose of each change

- Reviewing each change for impact on safety, health, environment

- Authorizing the implementation of the change

- Reviewing additional risks introduced into the process

- Setting a timetable for when temporary changes are to be removed or reevaluated

- Updating process safety information

- Revising or developing new operator and maintenance procedures as necessary

- Training all employees and contractors who are affected by the change

- Maintaining the configuration of the plant.

FDA regulations 21 CFR Part 211, 21 CFR Part 600, and 21 CFR Part 820 do not explicitly require change management. However, there is the implicit dictate to manage changes that affect a process, since they can inadvertently introduce new hazards or compromise safeguards that were built into the original design of the process.

If one thinks about it, management of change is the foundation of cGMPs. It is the control function that serves as the main interface between the document control system and the management system. Its primary role is to deliver information to enable timely response.

Well-conceived MOC procedures and a change control system will help to sustain compliance and improve delivery time. This requires that documentation and communciation keep up with changes, training keep pace with job function changes, procedures be updated to reflect changes and safe work practices and health standards be reviewed for impact.

Any proposed changes to existing facilities must be analyzed to determine their interaction and effect on the original design and on process safety. Based upon that analysis, appropriate action must be taken for all affected processes, equipment and procedures before the change is implemented. As the change control mechanism, MOC underlies all other processes and includes the final authorization of all proposed changes. In order to make change control effective without being burdensome and time-consuming, the actions required must be carefully worked out in detail and must include quick response for critical changes.

Data are collected from various plant operation sources, analyzed in the MOC system, and converted to information. This information can then be acted on by management.

Configuration management is an integral part of MOC. It determines how the “configuration,” or make-up of the facility, equipment and process, is handled. Top management must appoint a manager dedicated to MOC. However, a change control board, headed by the configuration manager, should manage the configuration and control changes. Its mission is to determine whether a proposed change will affect the configuration’s form, fit or function. Board members should include operations and maintenance professionals.

Four basic elements comprise a configuration management system.

- Identification – Identifying the equipment or facility and documentation. These documents include a technical baseline, drawings, procedures, process and information diagrams, equipment data sheets and forms.

- Control – Baseline design and the collection of documentation used to capture a proposed change. Documentation includes security, change proposal number, review/approval authority, issuance/distribution, issued date and effective date.

- Status Accounting – Recording and reporting of any changes to the documentation, including history files, tracking and closure.

- Verification – Ensuring that the Management of Change system functions as designed and the change matches the documentation, as well as performing system audits.

MOC and Continuous Improvement

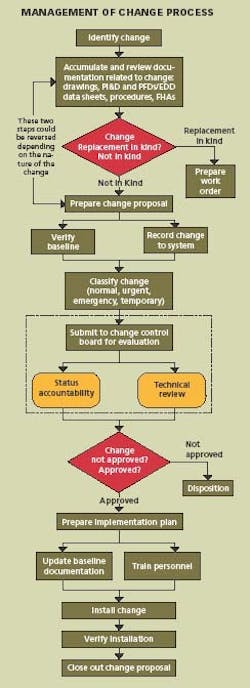

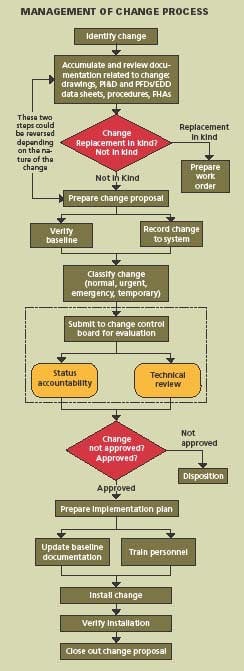

Changes to process, equipment, procedures, technology, material and organization are necessary for continuous improvement and a MOC system must also be continuously improved. The process requires eight basic steps:

- Identification

- Documentation review

- Change proposal

- Change classification

- Implementation plan

- Installation

- Verification

- Closure

Applying these steps, the system can be designed for managing the configuration and controlling the change, and then the necessary procedures and forms can be prepared. It is important that the system design come first. Specifically:

- Identify the change to be made

- Accumulate and review the baseline documentation, including drawings, procedures, P&IDs, equipment data sheets and MOC forms.

Prepare a Change Proposal

The change proposal is the vehicle used to document the changes in the specific application area. It is assigned a change proposal number, identifies approval authority, defines security, establishes issued date, effective date, and distribution. The baseline configuration and documentation are verified. From this point on, the change proposal must be controlled throughout the lifecycle.

Classify & Approve Proposed Changes

The Change Control Board must review, evaluate, and approve changes and then classify the change as normal, urgent, emergency, or temporary. In some cases, changes which are low-risk and low-cost may be approved by the Configuration Manager.

Develop An Implementation Plan

The implementation plan describes how the change will be put in place. Baseline documentation is updated. Operators and maintenance personnel are trained in the change.

Install the Change

This step speaks for itself.

Verify Installation

Track the status of the change. Verify that each step in the process is completed and the documentation matches the “as-built” configuration. Conduct a system audit.

Close Out the Change

Everything is completed and the cycle is repeated for the next proposed change. Managing change requires that the purpose and justification of the change be documented; change be reviewed for impact on safety, health and environment; cGMPs be reviewed for impact on GMP values; additional risk is not introduced into the process; authorization be documented; process information be updated; operating and maintenance procedures be revised; personnel who are affected by the change be trained; and configuration of the plant be maintained.

Sometimes changes can introduce new hazards or compromise safeguards built into the design of a process. Situations may occur that require an immediate change to protect the health and safety of the employees, facility or community. Immediate changes should have their own procedures that list steps to be taken and requirements.

Ensuring Training and Procedures In An MOC Program

A large part of Management of Change is maintaining up-to-date documentation. Situations occur where personnel are not aware of changes to documentation that could indicate training does not keep pace with changes in job functions. Typical problems include not being aware of changes in training or procedures, not maintaining up-todate documentation, and lack of a detailed procedure that describes the MOC process.

In order to eliminate these problems, corrective or preventive actions may be necessary, such as: auditing the training program and/or the procedure program for deficiencies; making training part of the MOC program; developing a detailed procedure that describes a process for initiation, review and approval; and documentation, training in change, and implementation of any changes.

The lack of agreement between training and procedures is a major industry problem, especially in a regulated environment. The question becomes which is correct — the training or the procedure?

Training in change is required for all changes in process and operation; technology; facilities and equipment; and procedures. It may be as simple as reading and initialing simple changes in a procedure if it does not affect skills or knowledge. In other cases, it could require developing new lesson plans to teach the new skills and knowledge, or developing and delivering structured on-the-job training.

Reinforcement training, an FDA requirement, is targeted for performers to maintain their skills and knowledge. Training in change should be critical and may cover much of the reinforcement training.

About the Author

John W. Rohrer is director of marketing and a field performance analyst for the Interlock Group, a performance improvement company. He is also a certified Six Sigma Yellow Belt and Quality Auditor.