From Laggard to Leader: A Formula for Lean Success

Lean management continues to be one of the most prevalent business improvement approaches in the pharmaceutical industry. Successful application of lean leads to shorter lead times with improved quality and customer responsiveness, resulting in enhanced revenues, reduced investment and costs. Unfortunately, as evidenced by the lack of significant improvement industry-wide in the inventory turns metric (the measure of a company’s “leanness”) over the course of over a decade,1 the industry has not been successful in ensuring sustainable improvements from lean.

WHY LEAN FAILS

What can pharma companies do to address this lack of progress and ensure their lean efforts are successful and sustainable over the long term? The place to start is identifying the root causes holding back progress. These consist of a lack of senior management commitment and involvement; an emphasis on driving cost reduction benefits (primarily in labor force reduction) over revenue enhancement and strategic benefits; and the siloed focus on application to manufacturing rather than across the enterprise.2

ADDRESSING THE CHALLENGES

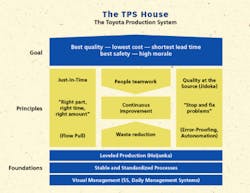

Addressing these challenges begins with gaining a clear understanding that lean is not just a “set of tools,” but a holistic operating system as illustrated by the Toyota Production System “house.”3

The TPS House is a simple visual representation of the Toyota Production System to show that TPS is a structural operating system, not just a set of techniques. The analogy is of a house that is strong only if the roof, pillars and foundations are strong; all elements of the house reinforce each other — a weak link threatens the whole system. For lean to be successful, all elements must be implemented starting with defining clear goals, developing a solid foundation, implementing process improvement tools, and ensuring that people — who are at the center of the system — are fully engaged and driving continuous improvement.

SUCCESS STARTS WITH LEADERSHIP

Over 90 percent of successful lean implementations have a strong leader who understands and lives lean.4 This must be an individual at the senior level who has strong leadership skills, understands the concept of lean needing to be employed as an operating system, and is committed to driving the change no matter what. The role of this lean leader is to drive the change through all levels of the organization, starting at the senior levels. In many cases, companies do not have the internal capacity and/or lean external consulting partners. It is important to vet potential consulting partners to ensure they have successful track records with lean implementations that include all aspects of lean — not just the technical tools, but also with driving the human elements (work center and problem-solving teams, Gemba walks, leadership training).

The first step for the lean leader is to build buy-in at the senior levels of the organization by ensuring that the implementation will directly impact the company financials. Results are needed in a reasonable period of time to build momentum and ensure buy-in via proof of concept. This is done by building a business case that is tracked throughout the lifetime of the implementation. Benefits should be determined by conducting an assessment to understand where the opportunities lie in terms of both financial and operational metrics, e.g., revenue by product line, production cycle times, inventory turns, right-first-time quality metrics, etc. Lean initially is counter-intuitive to standard accounting metrics, so education and buy-in with finance is crucial to ensure success.

LINKING LEAN WITH VALUE

There is a reasonable expectation amongst senior leaders that lean will produce significant financial and operational results, and that results will be achieved in short order. This leads to the expectation to “see results quickly,” which many times results in labor cost reduction. Labor costs are easy to measure while the strategic benefits of improved speed, quality, flexibility, customer satisfaction are more challenging to quantify.

Further, moving beyond cost reduction to benefits in areas such as revenue enhancement requires collaboration across the various functions. For example: marketing, sales and operations working collaboratively to increase market share by capitalizing on enhanced speed and increase capacity, or operations and product development collaborating on building quality into new treatments. Unfortunately, functions, divisions, and geographic units at most pharma companies remain strongly independent with the silo mentality deeply entrenched. This lack of collaboration is another contributing factor to lean implementation being isolated to “the four walls” of manufacturing versus the entire supply chain or product development.

Overcoming this challenge requires two things: the ability to identify financial benefits that are attainable within a reasonable period of time; and changing the culture to drive collaboration between individuals,

departments and function. For the first element, companies need to understand where the “levers” are in their organization that can drive the most improvement quickly. For this task, one can look to an improvement approach known as the Theory of Constraints (TOC).5 TOC looks at businesses as systems — a collection of interrelated, interdependent components or processes which act in concert to turn inputs into a set of outputs in pursuit of some goal.

TOC likens systems to chains, or networks of chains of dependent events. What factor determines the strength of the chain? Clearly, a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. TOC defines the weakest link as the constraint to the system, i.e., it is the limiting factor.

TOC posits that the greatest improvements come from addressing issues at the weakest links in the chain. Improvements at non-constraints have very little positive impact on the overall system and can even be detrimental.

Translating this analogy to a pharmaceutical manufacturing business, the “chain” is the supply chain which consists of a sequence of dependent events to buy things, convert them to something else (usually), and finally ship things to customers (or distributors) with a resulting sale. The strength of the chain is measured by the rate at which the supply chain generates money for the business through sales. All manufacturing companies have one of two possible locations for the constraint either internal or external. The question is: Can you meet existing customer demand with your existing processes and capacity vs. having excess capacity and not enough demand in the marketplace? This is a fundamentally important question for companies to be able to answer.

By identifying and eliminating waste, lean primarily frees up capacity. If the company has an internal constraint that’s located in manufacturing, then lean implementation will free up capacity and increase the speed at which companies can fulfill both existing and unsatisfied market demand, thus resulting in immediate improvements to both top and bottom line financials via additional sales.

However, if a company chooses to begin lean at a manufacturing site that does not have any capacity constraints, i.e., external market demand is the limiting factor, that freed up capacity cannot be used for additional sales. So what will happen to the additional capacity? With the pressure to “see results quickly” there will be a high likelihood of layoffs. Recall that the cost reduction viewpoint is one of the root causes of lean failures. Thus, there is a need to ensure that the right areas are chosen to implement lean.

Breaking a capacity constraint results in immediate benefits in terms of revenue enhancement — an area with far larger profit potential than labor cost reduction. It may be that there is a capacity constraint with some product lines, but not others, for example, life-savings treatments vs. less common treatments with limited market demand. Once these product lines are identified, the next step is determining the potential revenue enhancement benefits from implementing lean in these areas. Doing this requires determining the drivers of the capacity constraint(s), e.g., downtime of equipment, long setup-times, etc., and estimating the potential improvements from lean implementation to resolve these issues.

Lean implementation also results in a significant reduction in inventories, which frees up working capital and results in improved cash flow and reduced costs associated with holding inventory. Both revenue enhancement and

reduced inventories are significant opportunity areas that need to be assessed to develop a business case resulting in improvement initiatives that impact company financials in a relatively short period of time.

In the situation where the constraint is external, then it should first be evaluated which area of the business has the most opportunity for financial improvement in a relatively short period of time. This process starts with a thorough understanding of the nature of the competitive landscape for the company’s products. Do the company’s products compete on price, quality, speed (areas that are most impacted by lean implementations)? For example, if a customer is willing to switch suppliers to the one that can provide the fastest, most reliable delivery, then application of lean to the relevant production lines can provide the improvement needed to capture more business.

OVERCOMING CULTURAL CHALLENGES

Developing a culture that supports collaboration is a great challenge — one that many pharma companies have not been able to successfully resolve. Companies that successfully incorporate lean as an operating system have common cultural attributes of engagement, empowerment and accountability. To develop a culture that embodies these culture attributes, an assessment (culture polls, surveys, etc.) should be conducted, followed by leaders defining, aligning, and communicating a clear vision of the desired state, then leading the way.

Leading companies have driven culture change by conducting cross-company training programs for all managers to change their role from the traditional “command-and-control” model to that of “manager-as-coach.” Command-and-control culture is characterized by managers whose roles primarily consist of enforcing rules (attendance, making sure that operators follow SOPs, instructions, etc., while doing their work), dealing with interpersonal conflicts, solving problems and making decisions regarding any irregularities during daily work. In this environment, managers have the minimum skills and accountability required to perform at current levels with little or no ownership of work center performance, process improvement, or people development. As a result, the environment is typically one of being in constant “firefighting mode” — lack of collaboration, potential for adversarial “us vs. them,” and the lack of utilization of shop floor employees to their full potential — which lean would label as a waste.

By contrast, in the “manager-as-coach” model, the people manager takes on the role of coach. A coach develops the abilities of his/her employees to independently solve problems and implement improvements of ever-increasing levels of complexity and risk. The coach empowers people, drives accountability, sets the performance standard, collaborates and energizes people, enables the high-performance team culture, and develops their people’s capabilities. The end-result is dramatic performance improvement across KPIs, increased employee engagement, increased productive use of leadership time, collaboration, increased retention of high-performing employees, and the creation of successful leaders. Coaching builds systemic strength in an organization and enables a high-performance culture — ensuring that lean efforts are successful and sustainable. The lean operating model then provides the mechanisms to utilize coaching and collaborative teamwork via the self-directed worker team’s concept and cross functional “focused factories.”

BRINGING IT ALL TOGETHER

Key elements to ensure successful lean implementations include: top management commitment and involvement, building a business case that incorporates an understanding of the “levers” (constraints) to drive financial benefits in the areas of revenue enhancement and inventory reduction, and breaking down cross-functional silos by changing the role of the manager to a coach.

By incorporating these elements, pharma companies can ensure they can maximize their performance in the competitive edge factors of speed, quality and cost, while ensuring sustainability and continuous improvement for the long term.

REFERENCES

1, 2 Spector, Robert. Exploring the State of Lean in Pharma. Pharmaceutical Manufacturing, Jan/Feb 2018.

3, 4 Liker, J. The Toyota Way. McGraw Hill, 2004.

5 Spector, Robert. “How Constraints Management Enhances Lean and Six Sigma.” Supply Chain Management Review, Jan/Feb 2006.

[javascriptSnippet]