From the Editor: The Cost of Poor Quality, Too High a Price?

For drug manufacturing professionals, these are especially trying times. This month’s cover story, for instance, reveals that, at some facilities, even bench chemists and managers are being thrown into the breach, to help shore up operations and keep facilities running.

We see the signs of strain everywhere. Perhaps they are also reflected in an increased number of GMP compliance problems? Some manufacturers are also in the midst of consent decrees, which, according to some estimates, can cost well over $2 billion.

Regulators are connecting the dots between staffing and potential risk, with PIC/S, the international pharmaceutical inspection authority, suggesting that downsizing be added to the factors that account for potential GMP risk.

Quality problems present the public with huge potential costs, as Japanese engineer Genichi Taguchi, realized. For manufacturers, there are potentially huge external costs---for delayed product launches or approvals, severe actions such as consent decrees----but the intangible costs of loss of reputation.

Comment as cynically as you like on the recent announcement of J&J’s CEO’s early retirement, but consider the personal costs for anyone associated with quality problems. In the recent past, some manufacturing executives lower down on the corporate totem pole have even taken their own lives after major quality disasters.

Less dramatic are the internal costs, of wasted raw materials, scrapped batches, and the cost of investigations and remediation. They all add up. Do you know how, or can you quantify the level at your line, facility, company, or corporation?

Fortunately, efforts are underway to get those actually working in the trenches, to pin numbers on quality costs.

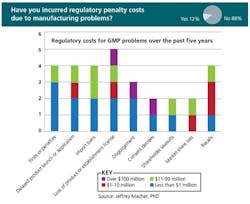

Last Fall, at ICH conferences in the U.S. and Europe, Jeffrey Macher, associate professor at Georgetown University’s McDonough Business School, presented results of a survey sponsored by PDA and ISPE, designed to clarify the cost of poor pharmaceutical manufacturing quality systems. As of last September, nearly 70 professionals representing 19 manufacturing companies, 37 facilities and over 150 products, had responded to the survey (you’ll find slides from Professor Macher on both PharmaManufacturing.com and PharmaQbD.com)

The findings might surprise you:

- Of those who responded, 12% had incurred regulatory costs due to GMP deficiencies

- 62% did not calculate the cost of poor quality at their production sites; only 11% had had such programs in place for five years or more

- 53% used manual methods to collect, analyze and publish data, with 29% using ERP and 6% using control charts.

- Roughly 92% did not evaluate the cost of improving quality against the potential cost of failure.

- Only 14% had conducted ROI analyses of their PAT programs

There is a reason to look out for poor quality, and it is not only to avoid crises like the ones that J&J and Ranbaxy are now contending with. It’s the fact that it makes good business sense and leads to improvements. In the survey, those who had begun efforts to measure the cost of poor quality had already begun to see some improvements, with 50% citing better on-time delivery, 46% pointing to reduced internal failures and deviations, and 26% noting overall cost savings of over 15%.