In the past half-century, the name of the game in manufacturing industries worldwide has been continued improvement of product quality. It has not been an easy road, nor has it been one without blind alleys, but almost universally across the world two key figures have stood out in the drive to progressively improve the quality of the things we make: William Edwards Deming (1900-1993) and Joseph Moses Juran (1904-2008).

While adopting rather different approaches to achieving quality—Deming was a low-level, “nuts-and-bolts” man while Juran preferred a systems approach—both were widely recognized as having crucial roles in the most dramatic quality transformation of the 20th century—the transition of post-war Japan from a “me-too” manufacturer of third-rate products into an economic and quality powerhouse whose ideas and approaches were subsequently widely adopted in the West in an attempt to simply stay competitive.

The impact of the approaches fathered by these two giants has been immense. There are now entire industries (electronics manufacturing, for example) where a generational change in manufacturing technologies is expected every five years or so. It costs about the same to build a new semi-conductor wafer-fabrication plant as it does to build a state-of-the-art pharma manufacturing facility, yet the semiconductor plant will typically be replaced (or sold off) after five years because it is no longer capable of meeting the newer state-of-the-art manufacturing requirements.

There are industries where manufacturing is so flexible that products are made for individual customers (look at the latest plants from Toyota, Nissan, and Honda, where cars can, within reasonable bounds, be made to order), and where small continuous improvements in product and process are implemented at the rate of tens or even hundreds a year. There are industries in which the same technologies that pharmaceuticals use for solid-dosage manufacture are used to control material texture, uniformity, and content to much higher levels of accuracy than pharma routinely achieves. The list goes on.

A Lonely Furrow

The current relevance of Deming and Juran to the pharmaceutical industry is more a result of the absence of the approaches they developed than in their direct impact, because the industry, almost alone within the manufacturing world, has by-and-large ploughed a lonely furrow, ignoring much of what the two taught other industries. Why? There are many answers, but one of the most significant is that the drug industry (and its regulatory mirror) has progressively spiralled down into a deep “Not Invented Here” (NIH) mindset over the last 50 years.

Deming had a particular gift for a turn of phrase (what we today would call a “sound-bite”), and one of his frequently quoted comments was, “You cannot inspect quality into a product. It is already there.” These are words which should be ringing down the corridors of many pharmaceutical companies given the widespread quality failures over the last 12 months. The message was quite clear 50 years ago:

- The quality of a product is determined by its design and the processes used to make it.

- To change the quality of a product, it is necessary to either change the design of the product or change the process used to make it.

- The bigger the change desired in the product quality, the more significant the change in the design or the process.

Strangely, this is a message to which pharmaceutical manufacturers and regulators have been strongly resistant for many years, cocooned in the belief that eventually more and more inspection will deliver the product quality for which all are striving.

It is interesting, therefore, that in the midst of ploughing their own, lonely furrow, the pharmaceutical industry and its regulators have chosen to lift a phrase from one of these giants and use it in an attempt to transform the industry: Quality by Design, taken straight from the title of a book by Joseph Juran.

This phrase was brought into usage in a pharmaceutical context by Ajaz Hussain (then of FDA CDER) at the height of attempts by the Agency to change how the pharmaceutical industry viewed its manufacturing process. Hussain had already launched the process that would lead to the PAT (Process Analytical Technologies) Guidance, a revolution in pharmaceutical manufacturing approaches which the industry is still struggling to adopt. It is clear from his presentations from nearly a decade ago that his use of QbD was a direct reference to the work of Juran, and by implication a direct attempt to persuade the pharmaceutical industry to adopt precisely the approaches catalogued in Juran’s book.

Back to the Book

What is Quality by Design? What does it actually require in practical terms? It is the process of delivering the highest practical quality of product, and to achieve this, the delivery of that quality must be explicitly considered for, and planned into, every phase of development, design, manufacturing and marketing operations. These processes must effectively become an integrated whole, the primary focus of which is quality.

Juran’s approach was, as ever, built upon looking at the systems within the manufacturing process which give rise to quality characteristics. For convenience, he broke them down into 11 areas, but this is really just a means to allow users to identify particular starting points. In fact, his approach was built on the premise that it was the system as a whole which had to be working correctly to produce a quality product.

Juran’s 11 areas can be simplistically put into three clusters. The first is associated with the design process and includes:

- Identifying Customers

- Determining Customer Needs

- Developing Required Product Features

The second is associated with the quality process within all the operating sections of the facility:

- Preparing for Quality Planning

- Strategic Quality Planning

- Multifunctional (Cross-departmental) Quality Planning

- Departmental Quality Planning

- Establishing Quality Goals

And the final cluster has to do with the actual manufacturing process:

- Developing the Process Features

- Establishing Process Measurements

- Developing Process Controls

It is immediately apparent just from these starting points that in Juran’s world, quality results from a highly sophisticated planning exercise in which all possible contributors (positive and negative) to the quality of the product are considered at the earliest stage. It is possible to provide a fairly simple summary of these clusters in the following way. The first stage is a comprehensive understanding of the customer, the customer’s requirements, and how these requirements can be met by adopting a specific set of product features. In most industries, this phase of Juran’s work is crystallized in the Quality Function Deployment (QFD), a highly structured methodology for mapping customer requirements against potential product characteristics with the objective of selecting the optimum balance of characteristics for the product.

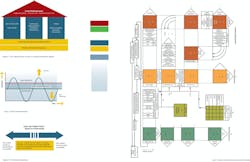

Figure 1. Quality Function Deployment (as implemented by Toyota)

A comparatively early example of QFD implementation from Toyota is shown in Figure 1. The pink boxes represent the matrices for the various levels of the initial phase, which correlates to a progressively more detailed application of product and process understanding to determine precisely what the characteristics of the product should be to meet the customer requirements. (It would be most interesting to know whether any pharmaceutical companies actually take this level of care to define the customer and their needs, rather than simply work through a set of "third-party" medical requirements. Certainly if any do adopt such approaches, they are not publishing the results!)

The second cluster represents an extensive exercise in understanding your own organization and how the operational actions of that organization can impact product quality. This happens at the broadest level and should include every operation within the facility. It is clearly evident from the extent of the subdivisions in the cluster that Juran regarded this as the central component of the quality operation. It is highly structured and starts with an initial, general quality planning exercise, then works its way down through the system from strategic operations, through interdepartmental operations and departmental operations, and finally down to determining the actual quality goals for the product throughout the organization. Only once these product quality goals have been established, in the light of the operational goals for the rest of the organization, is it then possible to move onwards toward the actual manufacturing process. (Quality planning at this level is not common in pharmaceutical companies. As a result it is, unfortunately, very common for there to be significant mismatches between departmental requirements, problems with information transfer, and even difficulties in defining the transfer of responsibilities at various stages.)

The third and final cluster concentrates on the manufacturing process, and on ensuring that it is capable of delivering product of the quality required in a consistent and efficient manner. It is only possible to define the process required, and the process measurements and controls that must be implemented, once the product requirements are clearly understood. This is in stark contrast to many pharmaceutical processes where it is common practice to “force” a product to fit into a pre-defined manufacturing process.

pQbD: An Incomplete Vision

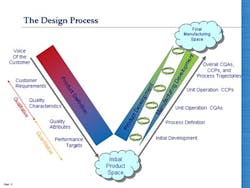

So having looked at Juran’s model of QbD, how does it compare with the QbD currently being formalized by regulators and adopted by pharmaceutical companies? It is clear from the many documents published by regulators, by organizations like ISPE, and from articles written by staff from many pharmaceutical companies (and presumably approved by their employers) that the current form of QbD is a long way from the vision that Ajaz Hussain had of implementing Juran in the pharmaceutical industry. Pharmaceutical QbD—let’s call it pQbD—seems to concentrate upon two areas: creating improved product and process understanding, and applying some level of risk assessment to the decision-making process. Unfortunately, as illustrated in Figure 2, the result is that the pQbD initiatives are only covering a limited part of the ground identified by Juran as necessary, and shown to be required in practical implementations across multiple industry sectors.

The next question is, of course, does this really matter? There are those who will argue that moving the industry forwards in any way is a step in the right direction. There is already clear evidence that the quality systems within many pharmaceutical companies are struggling simply to meet the very basic requirements of the existing regulatory system. (Simply look at the current level of product recalls.) Once these companies move into an environment where Quality by Design starts to place significant demands upon the structures within development and manufacturing facilities, the likelihood is that they will not be able to respond appropriately and that the level of failures will rise rather than fall.

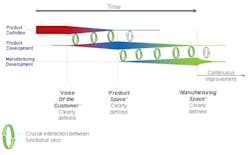

Deming, the master of the sound-bite, said, “We should work on our processes, not the outcome of our processes!” It is certainly true that in moving towards a QbD environment the industry should be seeking to design both product and process in a much more integrated fashion. The diagrams on the left give a clearer indication, firstly, of the way in which the development of manufacturing operations should be integrated, to ensure the achievement of inter-departmental quality goals which are implicit in Juran’s work; and secondly the interlinked form of product planning, design and development with manufacturing that ensures that the product meets the customer requirements, and that it is manufacturable within the constraints of the facility available.

Non-Standard Route

It is interesting to ask the question as to why the pharmaceutical industry has once again chosen to adopt a non-standard route to solve problems which have already been solved elsewhere. Given the steadily increasing numbers of recalls, the level of drug shortages because of problems in the manufacturing plants, and the increasing skepticism of the public (our customer) about the quality of pharmaceutical products, it is not reasonable to claim that the pharmaceutical industry has found a better, or even an alternative way.

Juran and Deming have had their approaches proven in the fire of highly competitive, low-margin, high-quality industries for more than 50 years. What is it that leads the pharmaceutical industry to walk away and take a different path? Are there underlying differences which differentiate the pharmaceutical industries from other industries and mean that it has to apply a non-standard solution? For instance:

- Are pharmaceutical processes more complex?

- Is the pharmaceutical industry more heavily regulated?

- Does pharma have longer leadtimes or greater up-front investment?

- Does the fact that the pharmaceutical industry is so closely connected to people and their well-being make it different?

The answer to all these is a resounding “No” because there are other industries in the same or more difficult positions which adopt the standard approach.

So a second question is, from an outside perspective, are there factors which make the pharmaceutical industry different? Interestingly enough, the answer to this is “Yes.” The biggest distinguishing factor is the extent to which the pharmaceutical industry is disengaged from the consumer (or end user).

Radical Change

The question then becomes, how do we put the ship on the correct course so that product development will genuinely deliver high quality products and processes? There are a number of basics which need to be changed before QbD (or even pQbD) can work effectively. These are:

i) The industry needs to treat regulatory requirements as a minimum standard for entering the marketplace, not as an acceptable standard for the consumer.

ii) The industry needs to apply consumer quality requirements for the product as the rule rather than as the exception.

iii) Product quality needs to become a competitive differentiator, not simply a requirement to enter the market.

iv) In support of iii), the industry needs to seriously consider making product quality information available to the consumer as a requirement.

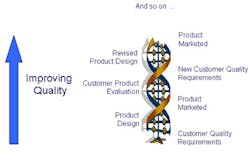

These changes will give rise to an environment where improved product quality becomes a virtuous spiral as shown in Figure 5.

Juran’s Quality by Design could genuinely help the industry to move forward and take the next big step towards achieving product quality that is world class. Will it happen in the current environment? The chances are that it will not—partly because the current pQbD is acting as a distraction and is not capable of moving the industry forward significantly, and partly because the industry itself is too focused on what is happening inside the industry to recognize that the changes in the world around it have left it crawling in the slow lane and threaten to leave it for dead.

There have been many initiatives from industry and regulators alike which have promised much, but eventually failed to deliver the necessary changes. Internally, there are many ways in which the industry and regulators could make significant changes if they looked to the outside world without the blinders of the last 40 years. However, if this fails (or more accurately, if industry and regulators do not work hand-in-hand to make this happen!), then the risk is that change will be imposed from outside by a world which is growing increasingly unhappy with the perceived quality of the products in its pharmacies. These changes will be much harder on the industry, but may be the only way forward in the end. Changes already suggested elsewhere include:

- allowing pharmaceutical companies to compete directly on the basis of quality. It is clear from the general market that consumers differentiate products on the basis of quality. If this information is available for drugs, then consumers can make an informed choice, and companies wanting to maximize market share will need to also maximise quality.

- requiring regulators to set progressively increasing quality targets as part of the drug approval. This is a large stick used to impose change.

- requiring drug prices to be decreased year-on-year after initial approval (at a rate which could realistically be compensated by ongoing improvements in quality and efficiency.) This assumes that pharmaceutical companies make improvements and that consumers can take a price reduction automatically on that basis.

- finally and most radically, separating the process of drug development and drug manufacture, and requiring that developers license to the highest quality manufacturer.

None of these are pretty options, but they should warn us that the quality gap between delivery and expectation is getting progressively wider. Quality by Design needs to become a mechanism by which it becomes possible to deliver significantly improved quality product to the consumer, not simply another way of meeting internal regulatory requirements which makes little or no difference to the man or woman in the street.

The final words go once again to William Edwards Deming: “Change is not mandatory; neither is survival.”

About the Author

Gawayne Mahboubian-Jones currently works for Philip Morris International as Program Manager—Excellence in Science and Design. His primary responsibilities in this role are the implementation of QbD and PAT. His initial degree work was in electronics and physics, followed by doctoral work studying bioelectronic membrane models. Since then he has worked in a variety of industry sectors, mainly applying complex instrumentation to the design and control of complex processes. Prior to joining PMI, he worked for seven years for Optimal Industrial Automation, providing PAT solutions to a wide range of pharmaceutical companies. He has trained the FDA PAT inspectors on control aspects of PAT, repeatedly spoken for the FDA on the subjects of PAT and QbD, and has worked extensively with ASTM E55 to create international standards to support the application of PAT.