Toyota's Meltdown: Lessons for Pharma on its Lean Journey

Toyota, whose Toyota Production System has been the model for Lean Manufacturing programs of all kinds, faced the greatest quality crisis in its history this year, when 8.5 million of its cars were recalled for safety problems. Consumer loyalty was shaken in a brand that, over the years, had become synonymous with quality. Sales fell, there were fines, and liability suits, all of which are expected to cost the company over $5 billion.

In March, the company’s president and CEO apologized and admitted that the company had strayed far from its original mission of product quality and customer satisfaction to focus on growth. “I fear we have grown too fast,” he said.

|

Experts on Toyota’s Lessons |

But the company reacted swiftly, appointing a senior management team, led by the CEO, to focus on consumer satisfaction and product quality.

In the headlines for the past few months, this story has been analyzed extensively, attributed to senior management hubris, lack of communication between corporate divisions, insufficient management attention to safety issues pointed out by company engineers, and pressures on a workforce already stretched thin to “do more with less.” Some analysts questioned whether applying Lean principles, by definition, meant compromising product quality.

Some analysts questioned whether there was any flaw in Lean Manufacturing itself, and whether applying Lean principles, by definition, meant compromising product quality. The answer is clearly no, says Robert Spector, Principal of Tunnell Consulting (King of Prussia, Penn.). “Toyota Production System and associated Lean methods were not to blame for Toyota’s recent problems. Over the years, many companies have achieved outstanding results using these methods,” he says. Instead, Toyota deviated from its own system, by responding too late to customer concerns and focusing too much on growth.

In addition, over the years, Spector says, Toyota had become far less lean, as its inventory turns went from 22 in the 1990’s to 10 in 2008.

Despite Toyota’s recent problems, its TPS and product development systems remain as sound as ever, agrees Bikash Chatterjee, President of PharmaTech Associates.

The drug industry only began to embrace Toyota’s operational excellence paradigms in the 1990s. Experts in pharmaceutical operational excellence looked at pharma’s progress in adopting Toyota principles, and the lessons that the pharma industry could learn from Toyota’s recent experiences.

The greatest challenge for pharma, as well as Toyota, will be sustaining quality while handling increasing complexity—both for products themselves, and the overall supply chain. “Toyota’s situation has created a greater awareness within the pharma industry, of the need to manage risk in a much more systematic way,” says Ulf Schrader, a partner in McKinsey’s German office and leader of the company’s Pharma/Ops joint venture,

“In the past, companies have looked at compliance at their own production sites. Now, they have become aware that over 50% of their cost of goods sold are actually from external sources, from contract manufacturers, raw material and packaging materials suppliers. Many of them don’t have the same systematic risk identification and management tools in place for contract partners as they do for their own sites.”

Another looming issue will be managing growth in emerging markets. “How do you create organizations that support growth of 10-20% per year in some of the emerging global markets, while still controlling the risks involved?” Schrader asks.

Toyota’s story pointed to the importance of establishing a culture of continuous improvement and focus on quality. “In order for operational excellence to become sustainable, it is culture that counts,” says Thomas Friedli, professor at the University of St. Gallen business school in Switzerland. “Even companies with very high quality standards cannot be complacent.”

In establishing a continuous improvement culture, pharma is at a much earlier stage of development than other industries, experts agree. “In the drug industry, the focus on product quality at a high management level, is simply not there,” says Gawayne Mahboubian-Jones, Program Manager, Excellence in Science and Design at Philip Morris International, “and the message that goes down through the company from management is partly what results in the [uneven] quality of the product that we get.”

Lean Development and Manufacturing: A Work in Progress

At this point, most pharmaceutical companies are still in a relatively early stage of implementing Toyota concepts. “There’s a huge spread in the industry as to what extent companies have implemented TPS concepts,” says McKinsey’s Schrader.

Another third are implementing the tools, but not very effectively, while another third has implemented them, but is still a long way from achieving world class results, particularly in standard work and in controlling process variability.”

“I think, we are very, very early in our journey of Lean,” says Pharmatech’s Chatterjee. Instead, companies have pockets of Lean. “It’s funny to talk with teams at some companies,” he says. “They’ll say ‘We have a very mature Lean program,’ but then I’ll ask them how they forecast raw material supplies. They’ll respond that they’ve bought all their raw materials for the year, so their inventories are through the roof.”

“Everyone gets OEE and sets goals around it. They get the concept of muda and it resonates with folks on the shop floor. But do they measure or reward performance within their organization, based on these concepts? No. They view them largely as gravy as opposed to the core principles that define process stability and process success, and that’s really the problem.”

At the University of St. Gallen, Friedli and his colleagues have been studying the industry’s adoption of concepts such as Total Production Maintenance, Total Quality Management, Just-in-Time, and effective management systems, for over five years.

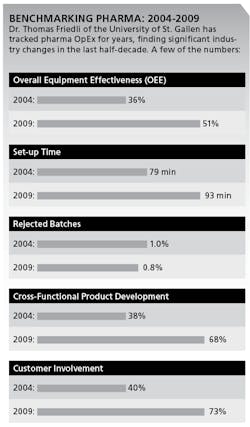

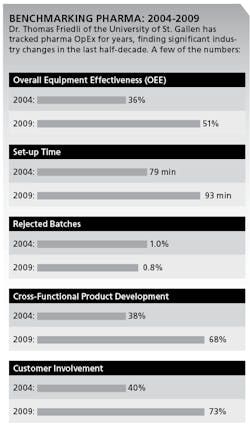

In annual surveys of over 160 sites between 2004 and 2009, he says, pharmaceutical companies have taken control of their formerly very low asset utilization. For example, Friedli says, use of OEE in Packaging has increased from 36% to 51%. (See charts below.)

More pharmaceutical companies are also improving quality, as measured by rejected batches, which fell from 1.00% to 0.74% between 2004 and 2009. Yet, pharmaceutical companies are still far from having any kind of “continuous flow,” smooth production scheduling or make-to-order manufacturing, Friedli says. For example, setup time increased from 79 minutes to 93 minutes from 2004 to 2009. Some pharmaceutical companies apply Jidoka, Friedli says, but not as part of a daily routine.

As far as Lean Six Sigma is concerned, Lean is more advanced in pharma than Six Sigma, says Chatterjee. “Even in generic companies, we are seeing this basic embracing of Lean, they like it, it’s accessible, it doesn’t have the complexity or the sophistication requirement that Six Sigma requires, it resonates with the workforce,” he says. “As long as you are not leaning and firing, simultaneously, people will support it. In terms of pharma’s implementation of TPS on the shop floor, I’d give the industry a C,” he says.

Annual productivity increases played a minor role in pharma. Responsiveness to customers was ensured by building excessive final product stocks. There were huge overcapacities. The results were a high amount of working capital, overproduction, redundant assets with low utilization and higher inventory as well as overhead costs. Within the "blockbuster paradigm" this was no real problem. Management paid much more attention to R&D and sales than to manufacturing and supply.

However around 2001 and 2002, Friedli says, manufacturing sites were required to strive for cost improvements within very short time spans because products were coming off patent. They reacted with a range of individual activities designed to cut variable costs, mainly focusing on the reduction of the number of rejected batches and the improvement of process quality.

Friedli calls this the "Best Practice" phase. Many sites did comparatively well, increasing yields, reducing variances of single process steps and final product stocks within their sites. But, Friedli says, take a closer look at the real root causes of major inefficiencies and little has changed half a decade later.

Redundant capacity, in most cases, is still there, Friedli says. Intermediate stocks within a site or between sites may be slightly smaller than they once were, but they’re still there.

Companies are only really beginning to think about how they can avoid unnecessary intermediate products and steps in order to create real flow, Friedli says, while make to forecast and real-time process control are seldom implemented.

Pharmaceutical operational excellence programs to date have already had some financial impact, but these projects typically affect only a narrow percentage of working capital, material and labor costs. Senior management has been disappointed with Lean Six Sigma, when, Friedli says, “There is still a lot of potential out there.”

Holistic Approaches Needed

Basically what pharma has been doing is taking some TPS practices and implementing them without looking at the overall philosophy, and that approach won’t work, says Mahboubian-Jones. “It gives you a marginal improvement,” he says. “With Toyota, they said, first, let’s get the product right, then the quality of the product right and then we’ll optimize the processes needed,” he explains. “Instead, pharma says, we got the product so we’ll just leave that, and will start looking at how efficient the development process is or how efficient our lab process are and the focus of these efforts is not exclusively but is primarily in development. Manufacturing is tacked on at the end.”

Instead, with Toyota and Lean examples in other industries, it’s manufacturing that actually incorporates the product quality, and makes it real. “However hard you work in development, if you haven’t got control of what’s happening in manufacturing, you will not ship a quality product,” he says.

Toyota in the Lab

Even while TPS implementation is far from mature in drug manufacturing, companies are already applying TPS concepts to the lab. Efforts at the quality lab level have been uneven, says Tadgh Prendeville, Director of North American operations for BSM, Inc. Companies get certain TPS principles, yet continue to stumble on standard work, a key pillar.

More companies are also looking at applying TPS to R&D, to shrink their time to market. A much better approach, says Chatterjee, is using Toyota’s product development system, which offers a more- structured approach, in terms of measurement metrics. Currently R&D has about a 2% chance of being able to accurately construct a molecule that behaves in the body the way it does in simulation. “We end up with a hunt and peck, trial and error process that’s costly and extraordinarily time-consuming,” he says, mentioning TRIZ methodology, used for product design in other industries, which is now being used in pockets of pharma to improve hit rate and bring drugs to market faster.

Knowledge Management

Observers say that pharma could learn knowledge management lessons from Toyota, particularly on the importance of integrating prior manufacturing knowledge throughout the product life cycle. “If we developed a controlled release product two years ago, took it to the shop floor, using the following formulation components and we had issues in manufacturing and product stability and degradation, that knowledge, that learning must be fed back into the next product in the development life cycle. That allows manufacturing to move upstream in terms of their participation,” says Chatterjee. “We need to get better at doing this in pharma,” he says.

This cannot happen if manufacturing is not viewed as an integral part of the entire pharmaceutical product value chain, as it is in automotive and other industries, says Mahboubian-Jones. “In pharma, there hasn’t been the level of investment and the development of manufacturing that there has been in other industries, says Mahboubian-Jones.

“If you look at the way for instance a Japanese car is developed, there are development people in there, but there are also manufacturing people saying, ‘If we go down this route, we’ll have this impact on manufacturing and we’ll need to do this.’ That’s why the pharmaceutical industry’s current implementation of quality by design, with a purely development focus, is next to useless,” he adds, “because quality by design means that you are changing the design to improve the quality of the product and the design means, the design of the product and the design of the manufacturing process.”

Management Support and Sustaining a Lean Culture

What helped Toyota face its current quality dilemma was a management focus on quality. And, in terms of pharma management committing to Lean, “It’s a journey. Toyota has been doing this for over 40 years, and even they stumbled,” says Chatterjee. “It’s something that requires relentless focus and reinforcement. In the pharmaceutical industry, we are not particularly good at this,” he says.

Observers point to the need to heed customer complaints closely. Such attention should come from the top level, some say.