Historic efforts to treat mental illness often hinged on what theories were in vogue.

Ancient treatments were focused on spiritual cures, involving rituals, incantations or exorcisms, and when all else failed — boring a hole directly into the skull to release the “evil spirits.”

Heading into the 19th century, the idea that patients could be “jolted” from episodes of mental illness took hold, which led to the use of electroshock therapy and cold-water baths, as well as the practice of injecting schizophrenia patients with large doses of insulin to repeatedly induce coma-like states.

The 1940s brought perhaps the most barbaric trend in all of medical history: the frontal lobotomy. “Easier than curing a toothache,” Walter Freeman’s ice pick lobotomies, which involved driving a metal pick through the eye sockets into the prefrontal lobes in order to “disrupt” the circuits of the brain, continued into the 1960s.

The ineffectiveness of treatment fads left many patients staring down a dark hole that was largely devoid of hope. But change was brewing, and an interplay of scientific discovery and cultural forces soon ushered in a bright new era of psychopharmacology.

In 1955, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved meprobamate, a “minor tranquilizer” marketed under the brand name Miltown to treat anxiety. The drug’s commercial success was largely credited to Hollywood elites, who famously passed the pills around at parties, even creating “Miltini” cocktails, using the tablets as garnish. The craze spilled over into suburbia and by 1965, more than 14 billion tablets of Miltown had been swallowed by Americans thirsty for a miracle cure.

With the stigma of seeking treatment for mental disorders lessening and the commercial potential for treatments illuminated, the mental health drug industry began its ascent. Hoffmann-La Roche’s Valium was approved to treat anxiety disorders in 1963 and became the most widely prescribed drug in the world between 1968 and 1981. Around that time, following on approvals of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in Europe, Eli Lilly began its work on what would become the first SSRI approved in the U.S. — an antidepressant that could potentially skirt the side effects of previous treatments. In early 1988, Prozac hit the scene.

As if on cue, President George H. W. Bush officially declared the 90s the “Decade of the Brain,” signaling a new era of neuroscience research. Prozac quickly reached both blockbuster and celebrity status as the green and white capsules graced the covers of magazines and newspapers, and became the topic of best-selling books and popular movies. A series of me-too SSRIs followed shortly after, including Pfizer’s Zoloft and SmithKline Beecham’s Paxil — with continued financial success.

The mental health sector was abuzz and it seemed like unpacking the complexities of the human brain — and finally bringing relief to millions of suffering patients — was within reach.

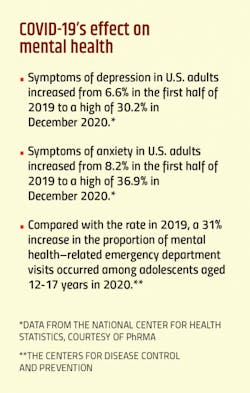

Now, over 30 years later, as the pandemic-stricken world stares down a dangerous mental health crisis, it is clear that there is still work to be done. The added pressures from COVID-19 have not only caused a staggering spike in mental health disorders, but have also provided a harsh wakeup call to worldwide inadequacies in mental health treatment.

But the burning enthusiasm for psychopharmacology solutions that came to a head in the 90s has seemingly grown dim. Faced with the daunting realities of high development costs, high failure rates and a still-incomplete understanding of the underlying pathophysiology, a once vibrant therapeutic sector has seen pipelines thin and a multitude of big players quietly back away. And yet, the need to find faster-acting, longer-lasting and more effective treatments for mental health has never been greater.

Can the pharma companies that remain dedicated to minding the ever-growing treatment gap find a way to fill the voids?

Pharma’s role in the void

It would be both inaccurate and reckless to blame the pharma industry for the widespread deficiencies in mental health care. The ongoing, multifaceted issue of mental health treatment is one that has vexed governments and health organizations around the globe for decades.

Recognizing the role that mental health plays in global development, the World Health Organization (WHO) issues regular updates on global progress via its Mental Health Atlas. The reports compile data from 171 countries on mental health policies, financing and availability and utilization of services — including availability of pharmacological interventions.

The latest version, based on pre-pandemic data, paints a disappointing picture of a worldwide failure to provide people with needed mental health services. This news is poorly timed with the alarming rise in mental health issues precipitated by the global COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the WHO, increased investment is required on all fronts, including mental health awareness and education; access to quality care and effective treatments; and research to identify new treatments and improve existing ones.

Pharma companies that choose to pursue mental health drug development are thus tasked with taking on broad, systemic issues in mental health care, rather than simply providing pharmacological solutions.

Ultimately, it’s about more than just making pills — it’s about addressing the system at large.

Pharma companies have looked to improve some of these systemic problems by getting more hands-on with patients — often teaming up with community-based nonprofits to increase mental health education. Over the years, companies have sought to build relationships with patient groups, professional societies and physicians in order to cultivate a more holistic view of the mental health crisis.

But tackling issues of the brain is not for the faint of heart, and a closer look at drug pipelines reveals a therapeutic area that has seen its share of hardship.

The toughest frontier

Scientists have dubbed the brain the “final frontier” of medical innovation.

The brain “is an amazing organ we unfortunately don’t know much about,” said Johan Luthman, executive vice president, Research & Development at Lundbeck, during a recent keynote address.

The 100+ year old Danish pharma company is an industry leader and one of the last companies standing that focuses exclusively on the unmet needs in brain diseases. The central nervous system (CNS) treatment space is typically segmented into drugs to treat neurological disorders (such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, epilepsy) and drugs designed to treat psychiatric or mental health disorders — Lundbeck develops both.

Luthman describes himself as “someone who has been hunting for drugs for over 30 years,” which is a lighthearted way of characterizing a career dedicated to seeking innovative treatments in a development space fraught with failure.

Historic data clearly demonstrate that the likelihood of success in developing a new drug for psychiatric and neurologic conditions is lower than in most other therapeutic areas.

Luthman says clinical trials of psychiatric drugs are often plagued with replication issues.

“Just because you have a pretty convincing phase 2 proof of concept trial doesn’t mean that your next trial will be positive,” says Luthman. “You still carry a very high development risk into phase 3.”

Citing findings from an Informa Pharma Intelligence Biomedtracker study, Kripa Krishnan, senior analytical consultant for Informa Pharma Intelligence, says that psychiatric drugs have a 52.7% phase 1 transition success rate (the likelihood the drugs will make it from phase 1 to phase 2). While this is on par with the average collective success rate across therapeutic areas, the phase 2 transition success rate for psychiatric drugs drops below average to 26.8%. When compared with the 48.1% success rate in hematology or the 38.4% success rate in infectious disease, psychiatric drugs appear to have a tougher time making their way through late stage studies.

“In the last 10 years, you see the entire market shrinking because a lot of these companies are shifting their trajectory. Either they are changing their pipeline drugs, or they’ve realized that they’re investing way too much into the clinical trials but are not able to find meaningful results,” says Krishnan.

Major players like Pfizer and Eli Lilly, who once ushered some of the most successful mental health drugs to market, now have pipelines almost entirely devoid of new mental health prospects. Currently, Pfizer has 85 pipeline medications in phase 1-3 and just one of them — a phase 1 drug being tested in geriatric anorexia — falls under the umbrella of mental health. Eli Lilly currently has 62 pipeline drugs in phase 1-3, none of which are being tested in the mental health space.

According to a 2020 PhRMA report, there are approximately 140 treatments currently in development for mental illnesses. While this is encouraging, it’s a small number when compared to other therapeutic areas, such as the more than 1,300 medicines and vaccines being developed for various cancers.

A blurred space

Research in the psychiatric space is further complicated by the fact that psychiatric disorders are often not isolated. A National Institute of Mental Health study found that over a one-year period, almost 50% of adults in the U.S. with any psychiatric disorder had two or more disorders.

Mental disorders also commonly co-occur with other illnesses. Diseases such as Alzheimer’s or cancer are often accompanied by severe depression. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) — a mental illness often associated with war veterans or victims of serious violence — has also been observed in cancer patients following diagnosis or treatment.

“Basically, any disease where you have a more chronic, progressive character, you see patients with periods of depression or mood disorders,” says Luthman.

Most recently, psychological ailments have been observed in long-haul COVID-19 patients. A May 2021 study found that a third of patients had been diagnosed with neurological or psychological symptoms, including anxiety, depression, PTSD and psychosis, in the six months after they contracted COVID-19.

Co-occurring disorders not only complicate diagnosis and treatment outcomes, but also create significant research barriers in controlled studies.

While the collective complexities of developing mental health drugs have been a deterrent for many drugmakers eyeing the space, those still in the fight are taking innovative approaches to filling the unmet needs of the market — and stand to reap fairly big incentives if successful.

Changing the development paradigm

Despite the obstacles, Luthman remains optimistic and says there is still ample opportunity for innovative research and successful drug development for mental health disorders.

“The big dream, of course, would be to identify the people that would benefit from a treatment with biomarkers,” says Luthman.

Achieving this would enable treatments to target defined subpopulations of broad diseases, or even rare and orphan diseases, identified by specific biomarkers.

“Every disease has a biomarker, we just need to find it,” says Luthman.

Unlike other therapeutic areas, there are currently no validated biomarkers for predicting, diagnosing or assessing psychiatric treatments — but scientists are getting closer.

Research from the Fujita Health University in Japan found that blood serum levels of anthranilic acid, a metabolite of the protein tryptophan, may help predict the onset and progression of depression. Researchers have also found biomarkers for depression in the form of specific brain activity patterns using machine learning and imaging tools like MRI.

This past April, a team at the Indiana University School of Medicine developed a blood test for a panel of RNA biomarkers, which they say can distinguish how severe a patient’s depression is, indicate the future risk of developing severe depression, and identify the risk of future bipolar disorder.

When it comes to developing drugs for depression, Luthman admits that the industry is likely still years away from qualified biomarkers — but it’s not an impossible dream at Lundbeck. The company is currently undertaking an early phase study using brain imaging modalities, and other brain function measures such as an electroencephalogram (EEG), to uncover potential biomarkers for antidepressant treatment response.

Lundbeck is also a founding member of the ERP Biomarker Qualification Consortium, launched in 2019 by pharma industry members with the goal of qualifying event-related potential (ERP), a specialized form of EEG that consists of measured brain responses to specific stimuli, as biomarkers for schizophrenia. If the consortium is successful, it could help streamline the development of new treatments for schizophrenia in accordance with FDA guidelines. The idea of new scales of measurement for psychiatric diseases hasn’t been an easy sell with regulators, who are used to more traditional, yet more subjective methods of measuring a new mental health therapy’s effectiveness.

But Luthman concedes that this level of scrutiny is necessary.

“The regulatory landscape is not tougher than it probably has to be,” he says. He believes that future advancements hinge on this progress, and it’s the responsibility of drugmakers to find a better way.

“We are working to get to a biomarker-oriented way of developing our drugs. The industry will not bring things forward unless we have more concrete readouts in the future,” Luthman says.

Researching neglected niches

While the most common mental illnesses in the U.S. are anxiety disorders, major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, the DSM-5, a reference guide commonly used by mental health clinicians, lists 157 different mental disorders.

The bulk of clinical research, however, is focused on the major indications.

“The psychiatric landscape is so skewed towards three indications [anxiety, depression, schizophrenia] that all the other indications are basically overlooked,” says Krishnan. “The number of trials catering to niche indications is significantly low to the point where it’s difficult to infer anything from it.”

According to Krishnan’s analysis of mental health therapeutics trial data from 2010-2021, over 70% of the more than 3,000 trials launched in the mental health space were focused on depression, schizophrenia and anxiety.

This lack of clinical research has led to a lack of tailored treatments for those suffering from more niche mental disorders. For example, while it is estimated that almost 10% of all women in the U.S. will suffer from anorexia at some point in their lifetime, there are no approved medications to treat the deadly eating disorder. Instead, many patients are prescribed antidepressants or other psychiatric medications to treat co-occurring mental health disorders.

Krishnan is currently researching opportunities for growth within the psychiatry landscape of the pharma ecosystem, and unmet needs in niche areas of mental health are a prime example.

“Let’s say you find a specific biomarker or invest in research for these niche indications. If you can bring a drug to market successfully, you can truly monopolize the area because there’s no competition right now,” says Krishnan.

Lundbeck has set its sights on another serious and under-treated condition where there is a great treatment need — PTSD. Nearly 6% of people worldwide experience PTSD in their lifetime, but during COVID, the incidence of health care providers and first responders experiencing PTSD has been even higher.

Lundbeck has both early and late stage potential treatments for PTSD. Brexpiprazole, a potent serotonin–dopamine activity modulator co-developed by Lundback and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Company is already approved under the brand name Rexulti in the U.S. for major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. The molecule is currently in phase 3 trials as a treatment for PTSD, and showed promise in a phase 2 study when used in combination with Zoloft.

Bringing next-gen and new-gen drugs to market

Critics argue that the mental health space has not seen a true psychopharmacologic breakthrough since the golden days of Prozac. And yet, many drugmakers are finding that there are still a plethora of treatment needs that can be met by improving existing meds. Luthman says that fine-tuning drugs can lead to better efficacy and fewer side effects, and the practice has an important place in mental health treatment.

“For every good drug we have, we have a responsibility to make sure we really characterize it fully,” he says.

Luthman points to Trintellix (vortioxetine), a third-generation antidepressant that Lundbeck discovered and jointly developed with

Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. Trintellix was approved by the FDA in 2013 for the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder (MDD).

“We’re still doing a few studies with Trintellix to unravel its full potential. We are also looking at people that have responded poorly to other antidepressants who might benefit from Trintellix,” says Luthman. “We are still invested in Trintellix because we believe there are more people who could benefit from it.”

Further studies of Trintellix led to a label expansion in 2018 to include the drug’s positive effect on processing speed, an important aspect of cognitive function that is often impaired in patients with MDD. Last year, Lundbeck and Takeda announced positive data in a trial that addressed another common symptom of MDD — emotional blunting. This symptom is a common reason for stopping medication and the study found that patients treated with Trintellix experienced emotional blunting less often.

And yet, the mental health space can’t survive without breakthroughs, and drugmakers are keenly aware of this.

“To be frank, we can’t keep approaching problems in the same way. We need to consider new targets, new modalities, new approaches,” says Luthman.

Fortunately, new approaches may be on the horizon, ushered in by the FDA’s 2019 approval of Janssen Pharmaceuticals’ Spravato. The esketamine treatment, a derivative of the licensed anesthetic (and unlicensed party drug) ketamine, is the first fast-acting depression medication ever approved. Its novel form of treatment via nasal spray delivers relief from depression within hours — addressing a major issue with current treatments for a disease where time is of the essence.

Yet, some of the obstacles surrounding Spravato— the fact that it must be administered in a certified facility and requires two hours of supervision by a health care provider following use — has left significant opportunity for other fast-acting depression drugs to enter the market.

Chief late-stage contenders include a once-daily, two-week, investigational drug being co-developed by Sage Therapeutics and Biogen for the treatment of MDD and postpartum depression; and a twice-daily combo of an older depression drug, bupropion, and dextromethorphan, a cough suppressant, being developed by Axsome Therapeutics for the treatment of MDD, Alzheimer’s disease agitation and smoking cessation.

Spravato has also helped pave the way for mental health treatments based off of traditional party drugs, including LSD, psilocybin and MDMA, the active ingredient in ecstasy or “Molly.”

“Right now, a lot of incentive lies in creating novel ways to approach mental disorders. These [psychedelics-inspired] drugs could change the paradigm of how depression is being treated,” says Krishnan.

The potential of psychedelics has spurred a rejuvenation in the mental health space, bringing young, promising companies such as COMPASS Pathways, Atai Life Sciences, Cybin and MindMed onto the mental health landscape.

Although many psychedelics-inspired treatments are demonstrating promising results, they will ultimately face significant regulatory obstacles, nudging the FDA into the unchartered waters of non-standalone treatments that will have to be prescribed in combination with psychological support.

To that end, New York City-based MindMed currently has several projects in various stages of development testing drug candidates designed to maintain the therapeutic benefits of psychedelics, without the hallucinogenic effects — with the goal of bringing non-hallucinogenic take-home medicines to market.

We’ve likely seen the end of an era of mental health treatments that gain notoriety through Hollywood parties and custom cocktails, but more targeted and effective treatments are closer than ever before. While the pandemic has been a wakeup call to global mental health care deficiencies, it is also an opportunity for the pharma industry to reignite enthusiasm in the therapeutic space, and play an active role in the overall improvement of mental health treatment.

About the Author

Karen P. Langhauser

Chief Content Director, Pharma Manufacturing

Karen currently serves as Pharma Manufacturing's chief content director.

Now having dedicated her entire career to b2b journalism, Karen got her start writing for Food Manufacturing magazine. She made the decision to trade food for drugs in 2013, when she joined Putman Media as the digital content manager for Pharma Manufacturing, later taking the helm on the brand in 2016.

As an award-winning journalist with 20+ years experience writing in the manufacturing space, Karen passionately believes that b2b content does not have to suck. As the content director, her ongoing mission has been to keep Pharma Manufacturing's editorial look, tone and content fresh and accessible.

Karen graduated with honors from Bucknell University, where she majored in English and played Division 1 softball for the Bison. Happily living in NJ's famed Asbury Park, Karen is a retired Garden State Rollergirl, known to the roller derby community as the 'Predator-in-Chief.'