Flawless: From Measuring Failure to Building Quality Robustness

Having zero errors — being flawless — should be the one overriding objective for quality in the pharmaceutical industry.

Over the past seven decades the pharmaceutical industry has grown tremendously and developed a complex system to ensure that patients receive high-quality products. Yet as the levels of complexity have risen, so have the numbers of quality incidents — far faster than the rate of growth. Something more is needed.

PROBING FOR ROOT CAUSES

The hard truth is that there have been big increases in the number of incidents reported by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) and in the severity of those incidents. Many of the most acute drug shortages can be traced to quality problems. And most regrettably, there are still instances where lives are lost or health is damaged as a consequence of bad product quality, as happened during the heparin scandal of 2008, or during the drug supply shortage for patients with Gaucher and Fabry diseases in 2009 to 2010.[1]

Pharmaceutical companies are attuned to the challenges, of course. They have been working overtime — and spending plenty — to ensure that quality issues are detected and reported in order to comply with regulators’ quality standards. They have been all too aware of the risk of site closures for noncompliance — and of the enormous damage to reputation that several industry leaders have already incurred. At the same time, the public’s expectations are rising. Now, the expectation for the industry is straightforward: zero lives lost, zero incidents, zero recalls and zero defects.

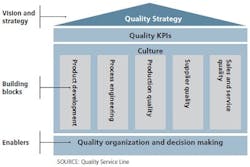

Figure 1. A comprehensive approach to a quality system is structured along three quality system components.

So why is quality still such an issue, despite decades of vigilance and in spite of so many advances and innovations in production methods and in pharma science and technology overall? In part, the rise in the number of incidents can be explained by steadily increasing product volumes — up by 6 percent per year in the past decade alone. The risk of errors has also risen with the increasing complexity of the pharma supply chain (for example, the number of SKUs on an average packaging line is increasing by 8 to 10 percent every year) and with the fragmentation of the market — from more industry players to more nodes on the supply chain. Moreover, new product introductions are more complicated, featuring everything from advanced coating materials to drug-device combinations to far more diverse patterns of usage by patients. Those factors alone add up to a fundamental challenge: simply to keep quality incidents at the same levels as today, the industry needs to improve control of its processes tremendously.A more fundamental challenge is that the pharma industry does not readily share learnings, particularly when those learnings stem from quality failures. Information that is shared tends to be focused on the failure incidents themselves, such as observations and warning letters. The industry bias toward punitive measures for noncompliance motivates pharmaceutical manufacturers to focus on tracking failures when they should be encouraged to investigate how to prevent failures in the first place. Interestingly, pharma does much less to learn from its failures than is typical of the nuclear, petroleum and aviation industries, for instance. The nuclear incidents at Chernobyl and at Fukushima, as well as BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig disaster, led to publicly accessible and easy-to-grasp explanations that delivered new ways of designing facilities, procedures and processes. The nuclear industry has a history of producing well-written reports that are easy for the general public to understand and are based on clear root-cause analyses that highlight technical, management and cultural failures. The nuclear industry also uses easily searchable databases that contain a wealth of quantitative information on issues such as frequency of failure modes. But there are no comparable levels of reporting and no similar analyses or forums for the biggest pharma incidents.

Additionally, McKinsey’s longtime experience in the industry has shown that many pharmacos are struggling to increase their process capabilities in line with rising expectations and ever-present cost pressures. Too often, these upgrades of the underlying processes and facility investments drop down the list of priorities.

There’s also the challenge of shifting mindsets across an industry that has focused predominantly on compliance rather than on truly knowing the root causes and effects of quality issues. Too frequently, we see failures attributed to individuals rather than being traced back to process or systems issues, fixes focused on retraining instead of permanent corrective actions, inspection responses focused on the warning letter rather than the spirit or intent of the observation. Many letters reference inadequate investigations and preventive actions. If it is tough to tackle the underlying processes and systems, it is markedly more difficult to shift the mind-sets of the quality group, not to mention those of the operations department.

There are other root causes. The industry is saddled with a set of products whose process design has been geared for speed to market, not for quality in mass production; there are few incentives to reformulate and retest products that were proven effective decades ago. Very few pharmaceutical manufacturers have found ways to make low-cost updates to existing processes and face expensive change controls or regulatory filings, which means that known quality issues or underperforming processes can linger for years.

Additionally, there is a persistent sentiment that “if we dig too deeply into quality issues, we may learn something we’re better off not knowing.” Indeed, the risk and costs of these counter-incentives slow the progress that pharmaco executives want.

The same is true for the compliance bureaucracy created by the interplay of regulators and pharmacos. Quite a few companies have upward of 30,000 standard operating procedures (SOPs). One organization found that collectively, operators in its factory were applying 10 million signatures a year to batch records, deviation records and so on. Think about it: if you were an operator with 90 or so SOPs against your name, could you be absolutely certain that you were always doing the right thing, every day and with every batch? More importantly, with so many SOPs to work with, how could you know which SOPs matter most to quality?

Similarly, change controls sometimes need dozens of signatures, a requirement that prevents fast turnarounds from the moment a quality issue is signaled to the point at which the pertinent process is fixed. The desire to eliminate risks has led to filing ever more variables and locking down specifications to levels that in some cases are literally impossible to maintain.

Perhaps most serious of all is the fact that quality is still too often seen as “something that the quality function does to us.” Full support for quality requires active daily support by senior leadership, not to mention constant attention on the shop floor from shift supervisors. It also requires employees and managers to be trained and capable of making judgments about risk.

Overall, a pharmaco quality leader today who wants to drive change faces multiple impediments and challenges.

RESIGNED TO ETERNAL VIGILANCE?

The upshot? It is not fun to work in a company that faces quality issues. Apart from the emotional burden of possibly harming patients, there is the extra bureaucracy of dealing with the aftermath of a crisis. Unfortunately, the converse is not necessarily true: a pharmaco without quality issues can still have inefficient and frustrating practices. Too often, quality expectations tend toward a kind of “eternal vigilance,” with the quality organization in a gatekeeper role, keeping a watchful eye across the organization to minimize risks and suppress changes.

We believe this does not have to be the case. Quality improvement can be as rewarding as operational excellence. Best-practice processes alleviate bureaucracy and give employees the time to focus on what’s truly important — that is, on reducing risks to patients. Building robustness in processes and products means that problems are prevented in the first place, leading to less rather than more need for quality oversight. The good news is that best practice in quality does not have to be derived from scratch. There is substantial overlap with safety, health and environmental best practices, and even with operational excellence and continuous improvement initiatives. The upshot: pharmacos can learn not just from the quality best practices of others in their industry but from a wide range of practices and industries.

A best-practice quality system has quality leaders who not only help to set standards but also are teachers and coaches who help the rest of the organization become stronger. As such, they can strive to build better systems, better culture, and more-robust practices that directly reduce the risks of quality shortfalls.

Putting such systems and cultural norms in place never happens by accident. McKinsey contends that pharmacos should be deliberate in benchmarking where they stand versus the relevant regulatory requirements, versus other companies, and even versus themselves on their best days. They should explicitly target clearly defined improvements and set up the right lean production and quality systems. After that, they need to seek out specific opportunities, projects, and cases where they can deploy their new quality practices. They have to look systemically for opportunities to scale best practices across their operating networks. Last, but by no means least, they must look for ways to make continuous improvements — everywhere and every day.

Quality, then, is not about eternal vigilance. It is about building a system and culture of preparedness and robustness that can preempt many of the biggest risks.

THE MANY RETURNS ON GOOD QUALITY

Today, most pharmaco executives understand the returns on good quality, but in a world that puts a great premium on measures such as net present value, they struggle to justify those returns. In general, investments in quality are considered “compulsory due to compliance” and typically are outside of the routine investment approval process. McKinsey’s argument is that this stance fails to account for risk mitigation and undervalues the business impact of quality. Given the significance of the costs of noncompliance and the size of the opportunities to improve operations outcomes, quality must be managed not only with attention but with intention.

Considered in their broadest sense, the benefits of high quality are underestimated. Worldwide, pharma remains one of the most innovative industries in terms of research. So why can’t it have the same reputation in quality? An impeccable quality record and sterling quality processes would be — can be — an inspiration to patients, doctors, regulators and employees alike.

At the same time, quality should be a source of renewal for the industry. It should be the reason for new research into better clinical trials, clearer product characterization, improved production methods and more effective shop-floor operations — plus the inspiration for making products at much lower cost than ever before. It should enable pharma to stand tall as the industry with an outstanding quality record, with the ability to produce products that epitomize trust in corporations.

Put simply, pharmacos, together with their employees and investors, could reap rewards on many levels if their quality systems enabled results that are as close as possible to flawless.

So what would it take to attain such levels? The short answer is that it takes considerably more than most pharmacos are doing or even aiming to do today. The mark of the true leaders in quality will be visionary step-change approaches, not incremental evolution.

We hope the industry can shift its emphasis from “eternal vigilance” to “production system design,” which will help to achieve a performance that is close to flawless.

This article was originally published in the book entitled: Flawless: From Measuring Failure to Building Quality Robustness in Pharma

REFERENCE

[1] FDA briefing, March 19, 2008; “Drug tied to China had contaminant, FDA says,” New York Times, March 6, 2008. Andrew Pollack, “Enzyme Drug Is in Short Supply”, New York Times, Sept. 15, 2011.