Getting drug quality right the first time

A well-functioning Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) program can make the difference between a deviation being corrected and prevented the first time, or reoccurring deviations that require reopened investigations — wasting limited resources and potentially causing product quality issues.

It’s important to remember that a well-functioning CAPA program starts with a well-functioning investigations program. After you recognize you have a problem, the first step is investigating the deviation and determining the root cause. The root cause(s) will direct how, what and where the company will take corrective and preventive action.

Ultimately, as regulators note in ICH Q10, “CAPA methodology should result in product and process improvements and enhanced product and process understanding.“

In his seminal book, quality guru Phillip Crosby succinctly states, “Quality is free. It’s not a gift, but it’s free. What costs money are the ‘unquality’ things — all the actions that involve not doing jobs right the first time.”

To that end, setting up a CAPA quality system surrounded by adequate procedures, monitors and metrics to ensure that nonconformances do not occur now or in the future is the best and least costly way for a company to deal with any issues or defects.

Removing blinders

While the two terms in the CAPA acronym may sound similar, there are crucial differences between ‘corrective actions’ and ‘preventive actions’ and when they’re appropriate.

Once investigations and corresponding CAPAs address the root cause, impact on material or product and the direct correction to the issue (i.e., immediate correction), then the corrective and preventive actions must be addressed. Corrective actions are taken to prevent the reoccurrence for a specific product or operation, while preventive actions prevent any occurrence for all products or operations.

One of the most useful strategies for investigations is to ask questions and avoid assumptions. Alongside inquisitiveness, fishbone diagrams (Ishikawa Diagrams), fault-tree analysis and the ‘5 Whys Method’ are great tools that can be used to widen a company’s ability to determine adequate root cause, which leads to robust CAPAS.

When conducting the investigation, companies must review multiple systems including manufacturing processes, machinery, equipment, environment, specifications, raw materials and people. Deviations are not limited to these systems and other systems should also be evaluated as necessary, but many deviations do reside within one of the listed systems.

Another way to look at this concept is the metaphorical horse with blinders, where the blinders are used to keep the horse focused and moving forward. This same metaphor can be used to think about the investigation and CAPA process. If you go in with blinders on, just looking at the issue right in front of you without reviewing other interconnected systems for issues, important details can be missed and more costly problems may result.

Once all the elements of the deviation have been investigated, the narrative of the investigation and its linked CAPAs should explain when and what happened, and who was involved. The narrative should also document the solution that was implemented to correct and prevent reoccurrence of the issue. This includes a rationale for the root cause identified during the investigation. All these items should be well-documented within your quality system.

Elements of an effective CAPA system

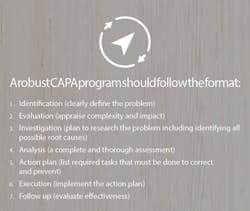

A robust CAPA program should include a well-documented system that identifies the true root causes of a deviation, including nonconformances, system failures or process problems. In addition, the CAPAs must address the root causes and identify the corrective action for remediating the deviation. Then, the appropriate correction must prevent the deviation from happening again.

The U.S. FDA’s Quality System Approach to Pharmaceutical CGMP Regulations guidance states, “CAPA is a well-known CGMP regulatory concept that focuses on investigating, understanding and correcting discrepancies while attempting to prevent their recurrence.”

The agency further defines CAPA as a “systematic approach that includes actions needed to correct (‘correction’), prevent recurrence (‘corrective action’), and eliminate the cause of potential nonconforming product and other quality behaviors.”

The Q10 Pharmaceutical Quality Systems guidance from the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) further details what is expected in a CAPA program: “The pharmaceutical company should have a system for implementing corrective actions and preventive actions resulting from the investigation of complaints, product rejections, nonconformances, recalls, deviations, audits, regulatory inspections and findings, and trends from process performance and product quality monitoring.”

Qualified staff (with proper training, education and experience) should run the CAPA program and incorporate meaningful metrics to track the performance of overall systems and provide early warnings for deviations/nonconformances. An appropriate Subject Matter Expert (SME) should be included in the process. Management should review potentially adverse information, oversee the overall adequacy of the CAPA program, and remediate identified deficient areas, including those that may need capital investment.

Once the appropriate solution has been implemented, evaluating its effectiveness should be ongoing. There should be a process for monitoring the recurrence of the deviation and closing out of the CAPA once the solution has been confirmed effective. All these items must be documented within the quality system.

The same level of depth and rigor of a CAPA for one issue may not be required for every deviation. For example, a small documentation error will likely only require a simple correction, while more serious deviations, like a confirmed ‘Out of Specification,’ will demand a much more robust investigation and CAPA. This follows the logic of Psychologist Abraham Maslow, who is quoted as saying, “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.”

The complexity of the deviation and its concomitant CAPAs not only determine the approach taken for the investigation, but also inform the timeline. For example, while some standard operating procedures may call for a 30-day timeline for investigations and CAPAs, that timeline may need to be extended. In this case, you’d need to document the rationale for the extension and get the quality department’s approval. A critical caveat here is everything in the investigation leading to a CAPA does not need a time extension. If your company is extending a lot of investigations, then it may indicate another entirely different problem.

Well-structured investigations

The key to establishing a successful CAPA is a complete and thorough investigation focused on finding the reason the deviation occurred. Failure to identify the correct root cause will result in possible failed effectiveness checks and the dreaded reopening of the CAPA. Everything plays a part in the investigation: people, machines, materials, processes, etc.

Management of these players is key to identifying the deviation’s root cause. The process behind the investigations is crucial in addressing the issue at hand. The aim shouldn’t be to find a single root cause that management believes to be the reason for the failure but to analyze all possible root causes across all systems. If an identified root cause isn’t the true reason for the failure, then the root cause can be eliminated. Each root cause eliminated narrows down the investigation. Any potential root cause that cannot be eliminated must be remediated, even if that root cause is not THE root cause of the failure.

A mistake companies make is identifying a root cause that needs remediation and stopping there. Companies should always identify all possible root causes and address them accordingly.

CAPA costs

When executed correctly, CAPAs help organizations remediate deviations/issues before they cause more technical problems and escalated costs. A practical example of an investigation and CAPA process is as follows: Company X had an investigation related to the detection of nonconforming vials, which were discovered prior to packaging. The inspectors on the line found the nonconforming vials, informed the quality team, and an initial investigation ensued.*

The quality assurance team correctly put the lot on hold while the investigation was being conducted. During the early phase of the investigation, the nonconforming vials were sent away to be analyzed by a third-party qualified laboratory. The results came back stating the discoloration was due to chemical contamination. The chemical in question was not part of the formulation or the container closure system and was not on any product contact surfaces within the equipment.

Company X eventually decided the contamination happened at the vial manufacturer and closed the investigation. One week after the initial observation of the discolored vials was opened and closed, the same issue arose with another product and the original investigation was reopened.

The company subsequently audited the vial manufacturer, but the results were inconclusive, with no identified source of the chemical responsible for the nonconforming vials. The company continued manufacturing while the investigation was ongoing and began a 100% incoming material inspection. A week later, a line operator noticed a vial exiting the depyrogenation tunnel that had a discolored blob in it. Manufacturing was stopped and the vial was sent to the contract lab for analysis. Once again, the chemical in question was the culprit. The company sent a consultant to do a full audit of the vial manufacturer while they continued manufacturing the product. Similar to the initial for-cause audit, the external consultant could not find the source of the chemical leading to the nonconforming vials.

After completing a more thorough investigation, the root cause was determined to be faulty cooling valves in the depyrogenation tunnel. This was previously identified by the company as a potential root cause in the initial investigation, but was not pursued because it was classified as ‘possible but highly unlikely’ and ranked lowest on the list. There was no alarm associated with the cooling valve which explains why the issue was not caught under routine maintenance checks. Once the problem was correctly identified, the proper and effective corrective action could be taken, including the potential costly endeavor of evaluating all products made on the line and looking at other lines with the same depyrogenation oven.

Cost of poor quality

Hypothetically, let’s say the cost of a critical deviation for Company X is a million dollars. When looking at the cost of poor quality (COPQ) of a defect, the cost is eliminated if and only if the pharma company’s quality management system (QMS) is organized and designed to detect, investigate, correct and prevent issues/deviations. If the company can prevent defects with their robust QMS, they will save money because they allocated sufficient qualified resources toward an efficient QMS — which in turn meant they didn’t have to address many defects/deviations and CAPAs. Hence the quality system pays for itself.

If the issue is detected within the company before anything is shipped out, the cost rises tenfold to ten million dollars. This is due to the company needing to address the now-detected issue and implement corrections (corrective action) to rectify the issue, as well as put measures in place to ensure issues do not occur in the future (preventive action).

If the company detects an issue in a drug product after it has been released by the quality and delivered to the customer, the cost raises tenfold again. The cost now includes recalls, as well as corrective and preventive actions. The cost of quality is important to understand — for Company X, they caused themselves a $100 million mistake.

Company X initially thought the issue seemed small and negligible, which led to an unfortunate quick closure of the investigation. Ultimately the deviation affected twenty-eight lots of manufactured products. These lots, produced over a two-month period for several clients, were rejected due to the nonconforming vials.

Company X should have utilized a more thorough investigation and root cause analysis strategy and taken more time to follow every possible root cause. Instead, the company chose what seemed like the easiest root cause and jumped to the wrong conclusion. Then the company quickly closed this initial investigation without a complete and thorough investigation, thereby creating a bigger issue and a compliance and business risk.

It takes diligence, thoroughness and a healthy number of questions to ensure you investigate, correct and prevent problems. But without this, the quality and efficacy of the drug product being manufactured could be jeopardized.