“When the thunderous battles of this war have subsided to pages of silent print in a history book, the greatest news event of WWII may well be the discovery and development — not of some vicious secret weapon that destroys — but of a weapon that saves lives,” read the ad for penicillin printed in Life magazine in August 1944.

Now, almost 80 years later, it’s antibiotics themselves that may need saving. The pace of innovative drug development has slowed to a crawl, while older antibiotics are rapidly losing ground in the fight against bacteria. And the results could be catastrophic for public health.

Every year, more than 1.2 million people worldwide die from antibiotic-resistant infections, and if no action is taken, it’s estimated this number will grow to 10 million per year by 2050. The issue is not limited to countries with inadequate health care either — around 2.4 million people could die in high income countries between 2015-2050 if we fail to tackle antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Public health agencies, scientists and industry groups have been sounding the AMR alarm for years and it hasn’t gone unheard. But despite the collective acknowledgement of the dire need to develop and manufacture new, innovative antibiotics to fight off these so-called ‘superbugs,’ the market dynamics simply aren’t cooperating.

Pharma R&D is famously expensive, time-consuming and fraught with risk. However, companies that successfully nab a coveted Food and Drug Administration approval and launch onto the market are handsomely rewarded, at least in theory.

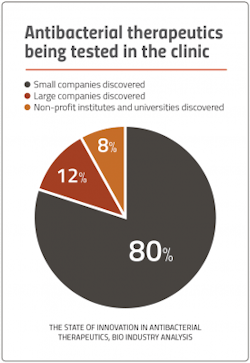

But antibiotics are a special case. While using antibiotics sparingly and in short duration can help preserve their effectiveness, this also makes it extremely challenging for companies to generate a viable return on investment for the innovations they bring to market. And given that the bulk of the players in the antibiotics biz are smaller biotechs, the risk of going belly up, even with a successful product, is very real.

“The antimicrobial ecosystem really is fragile and frankly, failing due to factors that are unique and make the sector completely different than other areas of medicine,” says Emily Wheeler, director of Infectious Disease Policy for the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO).

In recognition of how tough the market is, numerous mechanisms have been put in place — mainly in the form of discovery, preclinical and clinical funding — to stimulate the pipeline and give drug developers a running start. The global non-profit partnership, Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X), has awarded over $360 million towards early development of innovative antibacterial products. Public-private partnerships through the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), as well as collective industry ventures such as AMR Action Fund have invested billions of dollars towards late-stage development of novel antibiotics. Yet, the market is still steadily burning — and we are running out of time.

“Big Pharma’s not interested, investors have gone away — and it has just put the antibiotics industry in a really bad spot,” says Randy Brenner, chief development and regulatory officer at Paratek Pharmaceuticals, one of the few companies still active in the antibiotics R&D space.

Fixing the broken market now hinges on policy reform. While the leading bills on Capitol Hill would bring tangible relief in the form of financial incentives, the real game-changer lies in the global message the U.S. would send by passing them: The antibiotics market is viable, profitable and no longer ablaze.

The market’s slow burn

So how did we get here? Discussion of the U.S. antibiotics market often begins with fond memories of the ‘golden years’ of antibiotic discovery — a time ripe with the approval of novel drug compounds, during which the vast majority of classes of antibiotics used today were discovered.

This charmed antibiotic era, which spanned roughly from the 1950s to the early 70s, also coincided with a revolution in pharmaceutical marketing. Pharma companies began ‘detailing’ campaigns that aggressively targeted doctors with journal advertising, mailings and, for the first time, the deployment of sales reps. Pfizer’s first proprietary drug, a broad-spectrum antibiotic branded as Terramycin, hit the market in 1950 and famously launched the drugmaker’s use of a sales force to influence doctors.

This industry-wide combination of antibiotic development and marketing was so successful that the use of antibiotics in the U.S. almost quintupled between 1950 and 1956. While the concept of antibiotic resistance was known, most medical professionals were optimistic that the pharma industry would be capable of staying ahead of antibiotic resistance by keeping up its established pace of innovative drugs.

By the start of the 21st century, AMR was well-documented as a global health concern and ‘antimicrobial stewardship’ — the coordinated effort to promote responsible antibiotic prescribing — had begun to stem overuse, thus reducing the market demand for antibiotics. In 2005, reports of serious adverse events, including liver failure and death, began surfacing in conjunction with an antibiotic (Sanofi-Aventis’ Ketek) that had been approved by the FDA to treat upper respiratory tract infections. Under fire for what many viewed as an approval that should have never been granted, the FDA tightened its rules for clinical trial conduct.

“From around 2005-2012, there was a big lull in antibiotic development primarily due to regulatory uncertainty,” explains Brenner. “The FDA was changing guidelines and statistical approaches and making it really difficult for companies to know what the goalposts were to get products approved. The regulatory environment for antibiotics became too risky and too expensive.”

One of these companies was Lexington, Massachusetts-based specialty antibiotic maker Cubist Pharmaceuticals, which managed to snag QIDP designations for two of its late-stage antibiotic candidates less than six months after GAIN was signed into law.

In what Brenner cites as the “last big M&A in the antibiotics space,” Merck snatched up Cubist for $9.5 billion in 2014. Cubist had one blockbuster antibiotic already on the market, and one of its QIDP-designated drugs nearing FDA approval. Merck was looking to strengthen its position in anti-infectives, expecting the acquisition to add more than $1 billion of revenue in 2015.

But after several patents for its newly-acquired blockbuster antibiotic were invalidated, the market didn’t deliver for Merck — nor did it deliver for many of the smaller antibiotics companies that had eagerly entered the sector with promising late-stage products post-GAIN Act.

“The challenge that nobody predicted was what would happen when those products got approved. You started to see a lot of unsuccessful commercial scenarios, which really began to drive this whole market dynamic down,” says Brenner.

Like many other antibiotics at the time, Paratek’s lead candidate, a tetracycline-class antibiotic now branded as Nuzyra, had been stalled in development until the GAIN Act was passed. Nuzyra is somewhat of an anomaly on the antibiotics market — three years after launch, the drug is targeting about $100 million in sales this year. Nuzyra, however, has the benefit of being approved as both a once-daily oral and intravenous antibiotic, for community acquired bacterial pneumonia and certain serious skin infections. The company also nabbed a BARDA Project BioShield contract back in 2019 — which now has a total value of $304 million — to develop Nuzyra against pulmonary anthrax.

Even so, says Brenner, “one successful drug doesn’t make a successful market. We need other biotech companies to be successful commercially to change the dynamics of the whole space.”

The Pioneering Antimicrobial Subscriptions to End Upsurging Resistance (PASTEUR) Act establishes a delinked subscription program to encourage innovative antimicrobial drug development targeting the most threatening infections. The bipartisan, bicameral legislation was reintroduced to the House and Senate in June 2021 by U.S. Senators Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) and Todd Young (R-Ind.)

If passed, the law would change the way the U.S. government pays for critically needed antimicrobials, basing it on value to public health, not sales volume.

Contracts would range from $750 million to $3 billion and would be paid out over a period of up to 10 years or through the length of patent exclusivity. In return, patients covered by federal insurance programs would receive these drugs at no cost.

Status in HR:

40 co-sponsors; Last action: Referred to the Subcommittee on Health in Aug. 2021

Status in Senate:

3 co-sponsors; Last action: Referred to the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions in June 2021

Stalling for time

Those active in the AMR world are now looking towards additional policy reform as the fix.

“From BIO’s perspective and throughout the broader AMR stakeholder ecosystem, there is widespread agreement that a combination of policy reforms is critically needed to address the antimicrobial ecosystem and the unique challenges that the marketplace faces,” says Wheeler.

But policy enactment doesn’t happen overnight and the need for new antibiotics is imminent.

Recognizing this problem, 23 pharma companies — all members of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA) — joined forces with the World Health Organization, the Wellcome Trust and the European Investment Bank to launch the AMR Action Fund in 2020, raising nearly $1 billion.

The mission? Sustain the pipeline and bridge the gap by helping to bring 2-4 new antibiotics to market by 2030.

While the independently-run fund, which just announced its first two investments — Maryland-based Adaptive Phage Therapeutics and Pennsylvania-based Venatorx Pharmaceuticals — is often labeled as a ‘push’ incentive, providing funding to incentivize development, Henry Skinner, AMR Action Fund’s chief executive officer, argues it’s more.

Companies chosen by AMR Action Fund get more than just a cash infusion. Whether it’s helping portfolio companies facilitate collaborations or even work through manufacturing issues, the fund’s management team as well as its Scientific Advisory Board boast extensive experience and industry connections in antibiotic development and global health.

“I think of us as a venture capital group uniquely dedicated to AMR. Like a classic VC, we’re looking to invest in companies — providing not just capital, but intellectual contributions as well,” says Skinner.

Venture capital funding — or the lack thereof — has been a major red flag for the U.S. antibiotics market. According to a recent BIO report, venture capital funding for U.S. antibacterial-focused biopharma over the last decade was $1.6 billion — paling in comparison to oncology’s $26.5 billion.

In the absence of private investors, public-private partnerships, such as those initiated through BARDA’s Broad Spectrum Antimicrobials (BSA) program, have been key in terms of providing support to accelerate late-stage research and development. But at the same time, these partnerships have offered stark evidence as to why push incentives alone simply aren’t going to be enough to save the market.

Back in 2010, California-based biotech Achaogen was the first company to win a contract through BARDA’s BSA initiative. The company went on to win additional bids through BARDA, ultimately grabbing $124.4 million to fund the development of its lead drug, plazomicin, for the treatment of serious bacterial infections resistant to multiple antibiotics, as well as for disease caused by certain bacterial biothreat pathogens.

Everyone had high hopes for plazomicin. In 2014, it received a QIDP designation. In 2017, it was the first antibiotic the FDA designated as a breakthrough therapy. Around that time, Achaogen had a market cap of over $1 billion.

Plazomicin was approved by the U.S. FDA as a treatment for drug-resistant urinary tract infections — with a black box warning — under the brand name Zemdri in June 2018. But citing lack of efficacy data, the agency declined to approve the drug as a treatment for bloodstream infections. Falling short of expectations, Zemdri brought in a total of $800,000 from its launch in July to the end of the year, which wasn’t enough to offset the company’s losses.

Less than a year later after Zemdri hit the market, Achaogen filed for bankruptcy. The company sold Zemdri’s worldwide rights (excluding China) to India’s Cipla. QiLu Antibiotics Pharma in China picked up the Chinese rights.

“This was a big failure for the space. BARDA can invest in phase 2 and 3, but they can’t successfully launch products for us,” says Brenner. “Despite the desperate need for new antibiotics for public health, nobody can afford to develop and manufacture them if you don’t have commercial success.”

Fighting fire with policy

PASTEUR

‘Pull’ mechanisms are designed to complement ‘push’ mechanisms by incentivizing private sector engagement by creating market demand, sending signals to industry that a viable commercial market exists. To that end, the legislation on everyone’s lips right now is the bipartisan, bicameral Pioneering Antimicrobial Subscriptions to End Upsurging Resistance (PASTEUR) Act, which seeks to partially decouple ROI from the volume of sales, and instead base it on the drug’s value to public health.

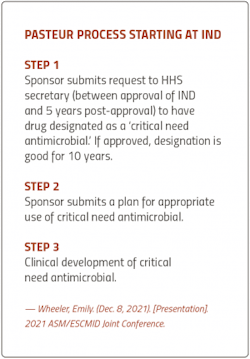

Under PASTEUR, developers would appeal to a Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) committee to have their drugs designated as ‘critical need antimicrobials’ — a criteria that would be defined within the bill and updated to reflect changing resistant threats.

Developers who qualify would be eligible for contracts ranging from $750 million to $3 billion, over 5-10 years, with the first payment granted upon the drug’s FDA approval.

While proposed policies tend to come and go, with most not managing to survive Congressional committee, PASTEUR, which was reintroduced last summer, has built up momentum.

“We continue to really see a steady increase of support on the PASTEUR bill, specifically on the House side. The House PASTEUR bill currently has 40 co-sponsors — and half of these co-sponsors were added since the beginning of 2022,” says Wheeler.

Growing recognition of the AMR crisis in Washington has given the proposed legislation legs. In fact, when President Biden announced his $5.8 trillion Fiscal Year 2023 Budget proposal this past March, the HHS Budget in Brief section specifically made reference to a delinked proposal designed to combat AMR, using wording that was reminiscent of PASTEUR.

“We were encouraged to see that because the budget often provides an indicator of priorities for the administration, in terms of both legislation and regulatory policies. To see AMR prioritized in any capacity, we chalk it up as a really positive step — and to build on that, the few details that were included had common elements to the PASTEUR proposal,” says Wheeler.

DISARM

While not as well-known as PASTEUR, the Developing an Innovative Strategy for Antimicrobial Resistant Microorganisms (DISARM) Act was reintroduced to Congress in June 2021.

The reimbursement reform legislation would allow Medicare to offer an add-on payment to hospitals that use a qualifying DISARM antibiotic to treat a serious infection.

This is an important piece of policy for antibiotics makers because the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Groups payment system (commonly known as the ‘DRG’) incentivizes hospitals to prescribe less expensive, generic antimicrobial drugs rather than novel antimicrobials — even if those new drugs have superior data.

Given that approximately 40% of all U.S. Medicare spending is on hospital services, Medicare reimbursement is a significant consideration for pharma companies looking for market success with new antibiotics.

“Even for a product like Nuzyra, which has both an oral and an IV formulation, to be successful, you still need to start in the hospitals. But because hospitals receive bundled payments covering both services and antibiotics, they are disincentivized to use novel antibiotics until patients fail treatment with cheaper generics first,” says Brenner.

Essentially, DISARM would help ensure that novel antibiotics can compete on a level playing field with generics.

Policies like DISARM are especially important to smaller companies with innovative antibiotics already on the market, such as Paratek.

“Now being on the market and seeing the challenges that are out there, a law like PASTEUR will give a couple of years to companies, but it’s not going to be sustainable long term,” says Brenner. “But policies like DISARM Act are really what we think will be the game-changer for getting this entire sector up and going again, because ultimately what the world needs to see are successful launches to change the commercial dynamics of these products.”

The Developing an Innovative Strategy for Antimicrobial Resistant Microorganisms (DISARM) Act would allow Medicare to offer an add-on payment to inpatient hospitals that use a qualifying DISARM antibiotic to treat a serious or life-threatening infection. The legislation was reintroduced to the House in June 2021 by U.S. Senator Danny Davis (D-Ill.).

If passed, the law would take away any notion that there’s a disincentive for using a newer, more innovative antibiotic.

Will cover FDA-approved QIDP-designated antibiotics, antifungals and biologics

Reimburses DISARM drugs at a set rate (Average Sales Price +2%)

For hospitals to be eligible, they must have a stewardship program in place and participate in the CDC’s antibiotics use/resistance tracking program

Status in HR:

3 co-sponsors; Last action: Referred to the Subcommittee on Health in June 2021

Cascading effect of new policy

One pivotal outcome of passing both PASTEUR and DISARM would be a jumpstart to commercial success. According to Brenner, market wins will trigger widescale change.

“With commercial success, you’ll see Big Pharma wanting to get back into the antibiotic space. Once we can incentivize the companies with deep pockets, that just opens the whole market up again for much bigger investments in R&D, manufacturing and commercialization,” says Brenner.

In terms of bringing investment back into the antibiotics sector on a global scale, Skinner looks to policy reform like PASTEUR as the industry’s “greatest hope.”

“If the U.S. passes PASTEUR or something like it, I think that leadership will help spur policymakers across other countries to pursue similar solutions. It would be a sign of good things to come around the world, and I think it would help attract other investors back in the space,” says Skinner.

While the U.K. piloted the world’s first ‘subscription’ incentive scheme for antibiotics, announcing last month that England’s National Institute for Clinical Excellence will offer Pfizer and Japan’s Shionogi flat rate contracts to make new antibiotics available to the National Health Service, the U.S. is still the world’s largest pharma market, generating almost half of total revenues worldwide. This means that the U.S. pharma industry, and the policies that benefit it, have considerable influence around the world.

Policy reform would also be good news for global organizations like the AMR Action Fund.

According to Skinner, with pull incentives and reimbursement reform in place, there would be an increase of capital flowing into the field, which would enable AMR Action Fund to invest in more companies and bring more products to market. This would start a chain reaction that would ultimately be “transformational” to the field.

Overall, pro-antibiotics U.S. policy says to the world that antibiotics are back from the brink of destruction.

“It would be an emphatic announcement that the market has changed and investment is welcome in the space. That will then invigorate the field and create robust pipelines — and we’ll have the antibiotics we need going forward,” says Skinner.

Building a fire-resistant house

While policy reform promises to bring much-needed rescue to a market currently engulfed in flames, the uncertainty that comes with pending legislation can be especially taxing for a pharma industry constantly tasked with optimizing pipelines.

Part of the onus falls on lawmakers and governments around the world in terms of providing both clarity and allineation on policies.

“AMR is a global problem, and we need to really align incentives and our thinking globally. If the U.S. has one set of expectations about what they’re going to reward, and the U.K. has another and Germany, a third and Japan, a fourth…that’s going to fragment this and make it extremely difficult to bring about the investment and change we need,” says Skinner.

But even as policy continues to unfold, drug developers can set themselves up for success by staying informed on the specific designations outlined in each piece of legislation — for example, which antibiotics would be designated as ‘critical need antimicrobials’ under PASTEUR.

“As the PASTEUR Act continues to move forward in Congress, there will be opportunities for it to modify slightly from its current form. But, staying up to date on the progress of the policy and the potential implementation process will be important for drug developers in terms of knowing what targets to shoot towards in order to have an opportunity to utilize these novel mechanisms,” says Wheeler.

If passed in its current form, PASTEUR will create a committee on critical need antimicrobials that will solicit input from a government advisory group comprised of external experts, including representatives from patient advocacy organizations and the pharma industry.

According to Wheeler, there are parameters included in the draft legislation right now that provide some guideposts; for example, looking to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report or the World Health Organization’s Global Priority Pathogens List to keep up on antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

“It’s already a difficult financing space, as we’ve seen from the multiple bankruptcies. If pull incentives are the solution to that, developers have to match their product to where those incentives are demanding the products be. If you fall short, you’ll fall into a black hole where you’re not going to get rewarded for innovation,” warns Skinner.

But ultimately, drug developers can cover most of their bases by setting a high bar for innovation right from the start, focusing on robust drugs that address critical unmet needs.

“When these rules get promulgated and the details emerge, if your drug is too incremental, it’s not going to make the mark,” says Skinner. “This is a field where you want to swing for the fences and make a big difference.”

About the Author

Karen P. Langhauser

Chief Content Director, Pharma Manufacturing

Karen currently serves as Pharma Manufacturing's chief content director.

Now having dedicated her entire career to b2b journalism, Karen got her start writing for Food Manufacturing magazine. She made the decision to trade food for drugs in 2013, when she joined Putman Media as the digital content manager for Pharma Manufacturing, later taking the helm on the brand in 2016.

As an award-winning journalist with 20+ years experience writing in the manufacturing space, Karen passionately believes that b2b content does not have to suck. As the content director, her ongoing mission has been to keep Pharma Manufacturing's editorial look, tone and content fresh and accessible.

Karen graduated with honors from Bucknell University, where she majored in English and played Division 1 softball for the Bison. Happily living in NJ's famed Asbury Park, Karen is a retired Garden State Rollergirl, known to the roller derby community as the 'Predator-in-Chief.'