China is a late-comer to the innovative biopharma arena and the country began its journey with just bio-generics. However, in the past decade, the industry has been making steady improvements and gradually built up its infrastructure for true innovations to take place in China.

At the macro level, the country has recruited thousands of talents with related research and industry experience from overseas (with many Chinese nations gaining experience in the U.S. before returning to the country). Simultaneous to this, clinical trial reforms have helped increase the country’s output and enabled biotech companies with no launched products to go public on both the Hong Kong and Shanghai stock exchanges. The reforms created a golden period for biotech start-ups in the country with a tremendous ability to raise funds, grow and become successful.

Consequentially, many more returnee scientists have seen the opportunities and returned to start their own biotech companies – with BeiGene, perhaps the most famous of these biotechs, having successfully launched an anti-cancer chemical drug into the U.S. market, as well as a PD-1 mAb in China. In fact, China has seen dozens of mAb therapeutics launched over the past decade and the country’s mAb capacity is now close to 1 million liters.

So is China already a biopharma innovation hub? And perhaps more importantly, can China-based biotechs like BeiGene successfully bring down the cost of innovative drug development?

Current situation: innovation in a ‘fast-follow’ fashion

To put the question into a wider global context, despite all the excitement, China still lags behind U.S., EU and Japan in innovative drug development. According to a report from the R&D-based Pharmaceutical Association Committee (RDPAC) released in March 2021, China’s innovative drug market (innovative drug according to Chinese standard) comprises only 9% of the total China market whereas the percentage is over 20% in other G20 countries and over 50% in countries like U.S., Germany or Japan.

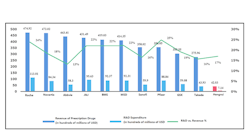

For example, the R&D expenditure of leading Chinese drug developers such as Hengrui Pharma is only $4.2 billion in 2020, less than 10% of MNC giants including Roche, Novartis, J&J, etc. (Figure 1). The contrast in IP is also significant. Hengrui applied for 471 and 373 patents in 2020 and 2019 respectively, while Roche applied for 2122 and 2082 patents in 2020 and 2019 respectively.China’s relative weakness in innovation also becomes more evident when we take the nature of the innovation from domestic developers into consideration. Most, if not all innovation which has taken place in China’s biopharma sector are ‘fast-follow’ or belong to ADC and bi-specific categories, instead of ‘first-in-class’ biotherapeutics. The mAb therapeutics and cell therapy from domestic developers are usually for established targets, and the biologics from domestic developers getting BLAs are either biosimilars, or bio-betters. More often than not, the more innovative pipelines currently under development by domestic biopharma companies are in-licensed from overseas. Domestic developers see ‘fast-follow’ as a strategy which could minimize risks of pipeline while offering good market potential, whereas investors also tend to shy away from first-in-class projects. According to China Economics Review domestic VC usually prefer ‘bio-better’ of biologics with FDA-granted BLAs, or at least those with existing publications in prestigious scientific journals.

Consequently, with such ready access to capital, China’s fast-follow ‘innovative biotherapeutics’ sector has become very crowded. For example, the country has granted 14 BLAs to PD-1 and PD-L1 mAbs, and dozens more have come into the clinical stage. And although PD-1 is now often taken as a negative case for domestic developers, new targets and new route (bi-specific, ADC, cell therapy, etc.) are still proliferating. Claudin 18.2, a relatively new target, is an example. Globally, Japanese company Astellas Pharma is the leader with claudiximab at phase 3, but in China ~20 developers are working on the target, with some at phase 1 already.

The developers will often claim their projects as ‘me-better’ (bio-better) but most industry insiders say the majority of these projects are ‘me-different’ (biosimilar) in nature. “Domestic developers have a mindset that it is ok as long as my project is not totally identical to those of my competitors,” one developer said during a recent interview with BioPlan.

Current trends put the future of China’s innovation at risk

#1: The policy on drug price control (VBP and NRDL negotiation) will hurt market prospect of fast-follow drugs.

China, unlike the U.S., has a drug reimbursement system which is heavily dependent on the national health care insurance program, while only a very small portion of the population has commercial healthcare insurance coverage. In fact, before the wave of BLA to mAbs from domestic developers started in 2017, mAb therapeutics were widely regarded as ‘luxury drugs’ available only to the affluent population able to pay out of their own pockets. However, since 2019 the Bureau of National Healthcare Insurance has arranged multiple rounds of negotiation with developers, which has successfully added mAb therapeutics into drug reimbursement list, but only with steep price cuts.

In 2022 the number of innovative drugs (according to Chinese standard) in the national reimbursement drug list has reached 119, and the majority of them enter the list with price reduction over 50%. PD-1 has been a perfect example. In 2019, the first PD-1 from a domestic developer, sintilimab, entered the national reimbursement drug list with a price of around $400 per injection. In 2020-2021 three other PD-1 mAbs from domestic developers entered the NRDL with price cuts over 70%, with Hengrui’s camrelizumab (200mg/injection) having its price cut from ~$3000 per injection to ~$400 per injection. Consequently, after these rounds of price cuts, PD-1 mAbs from domestic developers are significantly cheaper than their MNC counterparts. Previously, China’ s PD-1 market was therefore projected to be $13 billion, but now, with the price cuts, even optimistic projections are for only $3 billion.

Besides the NRDL entry negotiation, regulatory authorities in China are also planning for a Volume-based Procurement Program (VBP) for biotherapeutics. The program would push for further price cuts from developers in exchange for large volume procurement by government. The current policy applies to generic drugs (drugs which have more than two manufacturers making the same drug) and the first round of VBP has already taken place for insulin at the end of 2021, which resulted in average price cuts of 48%.

Whether the VBP program will in the future incorporate mAb therapeutics is currently unknown. Policy makers have already made it clear that VBP will certainly be applied to biosimilar mAbs. The question is to which products this will apply, as some predict that as bio-better mAb therapeutics targeting the same target (but not identical biosimilar) will be categorized as innovative drugs in China, VBP would not be applicable to them, while others are much more pessimistic. The latter group argues that with so many ‘me-different’ mAb drugs for the same target getting a BLA, regulatory authorities are likely to treat them as biosimilars sooner or later. For example, in the summer of 2021, China’s CDE published "Clinical Value Oriented Anti-Cancer Drug Clinical Development Guidelines." This required head-to-head comparative studies with the current best treatments, and it is widely regarded as a blow to ‘me-too’ drugs.

#2 Domestic developers’ export plans have not, thus far, had a smooth start

Analysts have lowered their expectations for China’s market as price controls get more stringent and now many developers are changing strategy and looking to the US/EU markets for growth. This is also likely to be a very challenging route as so far no biotech from China has achieved a BLA approval from the FDA. However, a number of mAb developers are currently applying for BLAs with mixed results.

For example, Innovent had its joint BLA application with Eli Lilly for sintilimab turned down by the FDA in March. The FDA cited a lack of international participants, with the trial solely dependent on clinical data from Chinese patients, as the reason for its failed approval. Junshi Pharma is also applying FDA approval for its PD-1 mAb and the FDA replied in May with a demand for a process change for quality control. Junshi is planning for a re-submission of the BLA application this year.

#3 Market valuation of domestic biotech companies has plummeted

Domestic developers are starting to feel the pressure of price cuts. Regulatory authorities intend to expand the volume of mAb therapeutics via lower prices, and developers have found this causes not only a current steep reduction in profit margins, but also a cut in overall revenues. For example, Junshi’s PD-1 mAb was launched in Dec 2018, but in 2021 its revenue from PD-1 mAb is only RMB 412 million, which is 60% lower than the RMB 1 billion revenue from the same mAb in 2020.

The net result is that biotechs may likely face more challenges than biopharma companies under the current pricing scheme, as they rely on external investment and the capital market is cooling down for China-based biotechs. In fact, the market valuations of domestic biotech companies has plummeted in 2022 (Table 1) even for the more prestigious ones such as BeiGene. According to China Economics Review, among the 34 biotech companies that went public on HK stock market in 2021, 24 fell on their first day of trading. Meanwhile, capital markets interest for investing in in-licensing models is also on the decline. On Sep 22, 2021, Shanghai Stock Exchange vetoed Haihe Pharma’s bid for an IPO on SSE STAR market due to its ‘heavy reliance on 3rd party technology.’ Haihe Pharma is developing 7 out of its 8 pipeline projects via in-licensing or co-development. This decision is perceived by the industry as a signal that the golden age for biotech companies good at ‘pseudo innovation and quick IPO exit’ will soon become history.

| COMPANY NAME | ALL TIME HIGH | CURRENT PRICE |

| BeiGene | $426.56 | $174.8 |

| Zai Lab | $152.82 | $42.82 |

| Legend Bio | $58 | $45.4 |

| C-Stone | $1.78 | $0.44 |

| CNTB | $25.25 | $1.37 |

| HCM | $42.93 | $13.02 |

| I-Mab | $80.88 | $6.01 |

Table 1: Stock price of China-based biotech companies went down in 2022

While it is clear the above-mentioned policy moves are projected to hit biosimilars hardest or the self-claimed ‘me-better’ drugs, it will inevitably also hurt domestic developers’ capability for future innovation. Chinese biopharma companies most often start from a biosimilar first model, before building the internal capability for mAb therapeutics development, including cell line development through to commercial production. They rely upon the profits generated from these projects – which are launched or close to getting a BLA – to provide the capital for more innovative and risky projects. This coupled with investors’ waning interest in China’s biopharma sector has led to industry insiders projecting many of these will cease trading within the next five years (based on BioPlan interviews).

#4 The Industry is making adjustments, but not necessarily via large investment in first-in-class therapeutics

The industry is of course making adjustments as its market prospects change, and biotechs are now considering the out-licensing model for revenue – letting go of their ambitions to become full-fledged biopharmas. Alternatively some biotechs, even those who have already gone through an IPO on Nasdaq, are looking for an acquisition exit route via a MNC big pharma. According to Bloomberg, I-Mab has held talks with other global drug makers about partnerships and investments, including clinical and commercial agreements in China. It’s also been seeking a partner to jointly develop its uliledlimab, or TJD5, cancer treatment in the U.S. and Europe, as well as other pipeline assets. Similarly, this August, Innovent Biologics and French pharma giant Sanofi announced a partnership to jointly develop clinical-stage oncology assets SAR408701 and SAR444245 in China.

Another issue is that developers are also starting to have an overabundance of capacity, one that many had not expected. When market prospect boomed for mAb therapeutics, many developers built or expanded their capacity with government subsidiaries, resulting in total capacity for China’s mAb sector quickly reaching up to one million liters. Now with quite a few competitors selling very similar products, the ones lagging (in development and revenue) would have idle capacity. Some developers, including Innovent Biologics which has revenues from its PD-1 mAb – over $417 million in 2021 – have even started a side business in contract manufacturing to put idle capacity into operation. Domestic substitution in bioprocessing supplies is another response that developers are trying to help reduce costs. Many domestic developers have incorporated supplies from domestic vendors, including single use bags (bioreactors excluded), cell culture media, or even resin, into their bioprocessing platforms.

Ultimately, despite the industry being fully aware of the necessary adjustment, its efforts toward first-in-class therapeutics is still relatively rare. So while some investors are turning to very early stage projects, due to relatively low valuations, there is still very few first-in-class pipelines in clinical stage in China. In the winter of 2021, Guangzhou-based Ming Med announced that its first-in-class HPK1 inhibitor PRJ1-3024 has kicked off a phase I clinical study in U.S. In June 2022, Innocare, a biotech startup founded by a prestigious returnee scientist Dr. Shi Yigong, announced that CM369, its first-in-class mAb against CCR8, is going to enter clinical studies soon having submitted an IND application to NMPA. The big question – a multimillion dollar one – is whether these efforts will turn into realized commercial successes.

When will first-in-class biotherapeutics arise and become mainstream in China?

China has clearly made significant incremental improvements to its biopharma industry. The country started with bio-generics (insulin, TPO, interferon, etc.) at the end of last century, turning to biosimilar mAb therapeutics in the first decade of this century, with the most recent decade witnessing a wave of ‘fast-follow’ mAbs. Domestic developers are now following relatively new targets, while first-in-class pipeline are starting to arise.

However, China may still need to wait for a drug reimbursement system which gives strong support for innovative drugs to make commercial successes for innovative biotherapeutics possible. This could take place either via greater coverage of commercial healthcare insurance, or by reforms at the national healthcare insurance program which highly favors first-in-class drugs. China also needs to deliver improvements in target-related basic life science research and translational research, the latter being an especially weak link at current stage. Meanwhile, China may still need to recruit inter-disciplinary talents (clinical research, pharmacology, basic life sciences, etc.) from U.S./EU to properly empower the growth of its bio industry.

This article is part of the CPHI Annual Report 2022. Ahead of the newly rebrand and returning CPHI Frankfurt, the CPHI Annual Report 2022 explores future trends, challenges and opportunities. Featuring a panel of more than 10 industry analysts and insights from across 400 pharma executives the report is window into both near and medium terms opportunities in pharma.