We live in a truly exciting time for the advancement of biologic treatments.

Biologics are the fastest growing class of therapeutic compounds in the United States, giving chase to the traditional small molecule model that defined the pharmaceutical industry for more than a century. While small molecule drugs still dominate the U.S. market in terms of quantity, the current pharma pipeline contains over a thousand innovative new biologic hopefuls — including a range of novel scientific approaches such as cell and gene therapies, RNA therapeutics and conjugated monoclonal antibodies.

But being at the top means you have to defend your throne. As the industry’s biggest biologics begin to fall from the patent cliff, lack of affordability and access is creating a huge opportunity for the next frontier in medicines: Biosimilars.

Per U.S. regulations, a biosimilar is highly similar to and has no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity and potency from an existing U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved reference product — with prices that can be almost 50 percent lower than branded biologics.

Why the failure to launch? In a sector where we should be making giant leaps, we instead appear to be inching forward at a less-than-desirable pace for those waiting for affordable options to pricey biologics, as well as for manufacturers who want to capitalize on a sizeable market opportunity.

What can be done to ensure that drugmakers and patients alike in the U.S. don’t lose the biosimilar space race?

Potential backed by fact

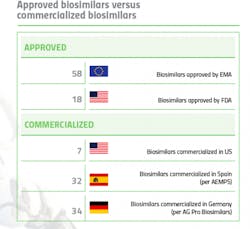

It’s well known that Europe is far ahead of the U.S. when it comes to biosimilar approvals and commercialization. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved its first biosimilar in 2006 and to date, 58 biosimilars have been approved in the EU, across eight therapeutic classes. Commercialization varies by individual country, but biosimilar penetration is healthy and it is not uncommon to see 30-40 biosimilars on the market in an EU country.

By contrast, the U.S. did not see its first biosimilar approval until 2015

But in this scenario, being behind offers a distinct advantage — there is already 10-plus years of market data available, courtesy of Europe.

“Biosimilars have already proven themselves in Europe,” says Edric Engert, founder of Abraxeolus Consulting and former head of the Biosimilars Unit for Teva. “There are over 700 million patient days in Europe [As of March 2018]. Biosimilars have been incredibly efficacious and incredibly safe,” he contends.

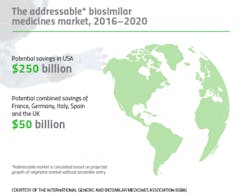

The financial benefits are there as well: Biosimilar medicines have already delivered savings of around $1.6 billion in the five largest EU markets alone.

Despite this preponderance of evidence, biosimilars still haven’t entirely taken root in the U.S., and experts say there are several explanations for the slow uptake.

Biosimilar exploration

The term that both clarifies and confuses when it comes to biosimilars is “interchangeability.”

In the U.S., there are two distinct regulatory pathways for biosimilar approval: A drug candidate can simply be approved as a biosimilar, or the drug manufacturer can add an additional step and apply to have its biosimilar approved as interchangeable — but this distinction requires additional data and carries a separate application fee. To date, none of the biosimilars on the U.S. market carry interchangeable designations. And this likely won’t change, says Christine Simmon, executive director of the Biosimilars Council, a division of the Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM).

“When every dollar counts, interchangeability designation doesn’t confer any additional product attributes or quality standards,” she says.

Not considering all biosimilars to be interchangeable is creating an acceptance barrier, even though interchangeability itself would not have an effect on the majority of biosimilars.

The FDA is clear about not endorsing interchangeability for “regular” biosimilars.

“When FDA carries out a scientific review of a proposed biosimilar, the evaluation does not include a determination of whether the biosimilar is interchangeable with the reference product and whether the biosimilar can be substituted for the reference product at the pharmacy,” the agency has stated.

This distinction is not just made by the FDA — it is written into the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) — which further complicates the issue by making interchangeability not just a regulatory term, but a legal one.

Globally, while the EMA does not directly make decisions regarding interchangeability, biologics are considered interchangeable upon approval. Per the EMA, “biosimilars approved through EMA can be used as safely and effectively in all their approved indications as other biological medicines.”

“Unfortunately, the U.S. is the only country that has a separate designation of interchangeability for an approved biologic. It’s another barrier that serves to foster the impression that an interchangeable biosimilar is somehow superior in quality to a non-interchangeable biologic,” says Simmon.

Exploring biosimilars in the U.S. was important enough to warrant the creation of a separate advocacy group. Formed in 2015, the Biosimilars Council came to fruition to address a void identified by many AAM member companies that were involved in the biosimilar space. The only U.S. trade association dedicated solely to the education and policy advocacy of biosimilars, the council has successfully extended AAM’s reach into the newest frontier in affordable treatments.

In addition to the confusion surrounding interchangeability, biosimilar manufacturers are up against several systematic commercialization challenges in the U.S. These barriers, says Simmon, “have forced the U.S. biosimilars industry into a perpetual state of infancy.”

“Each challenge needs to be identified as either systemic to the industry or unique to the product, therapeutic area or originator being challenged. It’s important to make this distinction since the approaches and solutions will vary across these two spaces,” says Engert.

Trust and confidence

Although generics and biosimilars are often lumped into the same category, the two are in very different evolutionary stages when it comes to public, physician, and payer confidence. Currently, generics account for close to 90 percent of prescriptions dispensed in the U.S. and have over a 30-year history of safety and efficacy with U.S. patients. By and large, the public trusts generic drugs.

Generics have the benefit of automatic substitution at the pharmacy level. Because of this, the rate at which generics penetrate the market after initial introduction is very high — with generics typically capturing most of the market (in some cases up to 90 percent) within a few months of entry. By contrast, the first product approved by the FDA as a biosimilar, Zarxio (Sandoz), became available on the U.S. market in September 2015 and ended the year with a 2 percent market share. Over three years post-launch, Zarxio has about 35 percent share of the U.S. filgrastim market.

Part of the onus falls on regulators. In March, the FDA updated its 2017 draft guidance on biologic drug naming — stating that the agency will continue to assign four-letter suffixes to newly approved innovator biologics, biosimilars or interchangeable biosimilars. The agency justified this as a matter of pharmacovigilance: In case of an adverse event, wanting the ability to determine whether its source is the biosimilar or biologic. Health Canada recently decided that they will proceed without the addition of a product-specific suffix, making the U.S. the outlier in this construct as nearly every other highly regulated pharma market does not require a suffix for the purposes of biological product naming. This includes the World Health Organization (WHO) which generally decides the naming construct for pharmaceutical product classes.

The biosimilar industry and insurers balked at this, arguing that the FDA should assign a biosimilar the same nonproprietary name as the reference product on which it was based in order to facilitate substitution by providers and pharmacists. This “meaningless addition,” says Simmon “creates a distrust and apprehension that is completely unfounded and not based on science.”

“The naming guidance is an artificial construct that the U.S. has created and is supported primarily by companies that are trying to avoid competition and protect monopoly prices,” says Simmon.

Unfortunately, a large part of the blame for eroding confidence comes from within the industry itself.

Pfizer is the leading biosimilars company worldwide by revenue, and the U.S. leader in biosimilar approvals with five, three of which are commercialized. According to Pfizer’s vice president, Corporate Affairs Lead, I&I and Biosimilars, Juliana M. Reed, one reason why the uptake of biosimilars in the U.S. has been limited relates to “dissemination of false and misleading information by biologic manufacturers that creates doubt and confusion among stakeholders about the safety and efficacy of biosimilars.”

The drugmaker has been bullish in its efforts to challenge practices that block competition and biosimilar options for patients. In August of last year, Pfizer submitted a citizen petition to the FDA, requesting that the agency issues guidance to ensure truthful and non-misleading communications are made concerning the safety and effectiveness of biosimilars. Pfizer also cited multiple, specific examples of misleading communication from brand manufacturers.

The petition was later supported by advocacy groups, such as the Biosimilar Council, as well as other drugmakers, including Novartis.

“Every time you spread misinformation around biosimilars, not only are you undermining the FDA approval, you are sowing the seed of doubt for providers and patients who are still learning about biosimilars,” says Simmon.

According to Pfizer, more still needs to be done. “We believe proactive measures must be taken to incentivize and cultivate a biosimilars market that prioritizes patient access,” says Reed.

IP battles and litigation

Innovation in biologics does not come cheaply. The innovator biologic process is characterized by long discovery and development times, costly failures and high clinical trial investments. Biologics, which generally rely on multiple patents, have a standard 20-year patent protection granted from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, beginning from the time the patent is filed (typically prior to clinical trials). Given that development is often a lengthy process, occurring after the patent clock starts ticking, the BPCIA provides innovator biologic sponsors with a generous 12 years of market exclusivity following the biologic’s FDA market approval.

However, branded pharma companies often seek to protect their products from competition by filing dozens (and in the case of AbbVie, hundreds) of follow-on patents, creating a “patent thicket” around their branded product. Challenging patents can be extremely expensive — even if some of the patents are eventually found to be invalid or unenforceable, patent litigation can be a huge deterrent for potential biosimilar competitors.

“This is a big problem because a biosimilar competitor has to have the financial wherewithal to challenge these patents in order to reach the market,” says Simmon.

The risk involved when there is patent litigation is often too great for biosimilar manufacturers to take on.

“Even if you think you can prove some of the follow-on patents to be invalid and others you can circumvent, are you really going to launch at risk if you look at the damages associated with a loss in such a case?” asks Engert.

Simmon clarifies that AAM and the Biosimilars Council are not anti-patent. “We both support and applaud true innovation,” she says. But like many in the industry, the group has seen too many examples of the U.S. patent system being abused and manipulated for the purpose of maintaining market monopolies — and this ultimately keeps drug costs high and slows innovation.

Attempting to rectify the country’s patent problem will involve legislative change, specifically to the BPCIA, which sounds like a longshot, but Engert claims it’s not as impossible as one might think.

“If you look at the history of the Hatch-Waxman Act, there was gaming of the system in the early days of the generic market in the U.S. and the Act was amended post-initial enactment to remove the loopholes that allowed a lot of the gaming,” he says.

“The question is with Congress and the Administration: Can they be called to task to find potential legislative solutions to the litigation and IP barriers that currently are diminishing the adoption of biosimilars?”

Additional shenanigans

“Shenanigans” were famously linked the drug industry after FDA commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb reprimanded pharma companies that employ tactics to stifle generic competition, calling on them to “end the shenanigans.”

According to Pfizer, these “anti-competitive behaviors incentivize the use of higher-cost originator biologics over biosimilars and create barriers to access to biosimilars.”

Rebate traps and bundling are prime example of such shenanigans hindering biosimilar competition. Once a biosimilar is launched, some brand manufacturers will provide payers with rebates for branded products that are so large that even a biosimilar coming onto the market at a reduced price can’t compete. Sometimes the brand manufacturers take it one step further, bundling rebates together for all products offered to payer. If the payer puts the biosimilar on the formulary, then the brand manufacturer will block the payer’s access to rebates for all of the bundled products.

“As a biosimilar developer, even if you get FDA approval and wind your way through the patent thicket and emerge from the other side, it won’t matter if you can’t get market share,” says Simmon. “It’s really a way for the innovator to leverage the rebate system to block biosimilars from gaining traction.”

While Gottlieb and the FDA have shined a bright light onto these anti-competitive tactics, putting a stop to these shenanigans is not within the agency’s authority. As with many of the challenges faced by biosimilars, change requires legislative action from Congress.

Unique challenges

While the systematic roadblocks faced by biosimilars are the most discussed, it’s the unique challenges that sometimes prove to be the most shocking.

“Challenges can be unique to the behavior patterns of specific companies, the specific therapeutic area, the infrastructure and the distribution channels that are in place,” explains Engert.

One example is the integration of biosimilars into oncology clinics.

Biosimilars are seemingly a natural fit for oncology, where the efficacy of biologics has been undeniable, but their expense has been a significant burden, contributing to the rising cost of cancer care. Five of the seven commercialized biosimilars in the U.S. are oncology-related.

But in an environment where the treatments being prescribed are curative rather than supportive, and immunogenicity is a top concern, physicians have proceeded with caution when it comes to switching patients. A 2018 statement by the American Society of Clinical Oncology on the appropriate use of biosimilars in clinical practice stressed the need for post-market evidence to provide more data on the risks and benefits of switching from biologics to biosimilars.

The payer system employed by most oncology clinics is an even bigger barrier. Engert points the “buy and bill” system often used in oncology clinics as an example of challenge unique to a particular treatment area. Buy and bill has been the primary method of distribution of specialty drugs, whereby oncology clinics purchase drugs from distributors to be dispensed in the clinic and then bill out to Medicare. The delta between what the clinics buy for and bill for makes up the majority of the clinic’s income.

The shocking part? Sometimes the gross margin is up to 40 percent for larger clinics.

“The larger clinics that are able to negotiate larger rebates can enjoy a gross margin of 40 percent simply through buying and billing the products they dispense. And since their profits are tied to rebates which increase with higher prices, how can a biosimilar gain traction in such channels if they are offering notably lower prices than the originator?” adds Engert.

Oncology is currently leading the drug innovator pipeline, which means future opportunity for biosimilar makers. But manufacturers pursuing oncology biosimilars have to fully understand the space’s unique challenges, including physician trust and the buy and bill landscape for clinics.

Next steps

While much of achieving the true potential of biosimilars hinges on better education and understanding, an action plan is still needed.

According to Engert, in order to advance biosimilar policy and regulations in the U.S., we need to turn aspiration into action. There is a difference between having an aspiration and possessing the understanding of the market to a degree that results in a solution.

“The aspiration is there and the objective is well-articulated, but there’s a huge chasm between articulating an objective and actually coming up with an action plan that is executable and that will be successful,” says Engert. “You really have to know what all the incentives — and sometimes misaligned incentives — are for the adoption of biosimilars.”

Forming a strategy

As a consultant, Engert has helped companies develop commercialization strategies for biosimilars by analyzing past behaviors of originator companies and creating different potential scenarios as to how originators might react to the launch of competing biosimilars.

“Patterns of behavior are incredibly important — it’s not the number of competitors potentially on the market, but more which competitors

are on the market,” says Engert. “Some have very rational behaviors that are very much tied to standard economic objectives of maximizing profits, but some are more pursuant of strategic imperatives at any cost.”

From there, biosimilar companies can form combating tactics to mitigate risks. Due to their nascence, biosimilars often require a marketing launch similar to that of branded products.

“Focus on commercialization tactics is going to be key going forward but drugmakers will nevertheless still need to go out and educate as to what a biosimilar, the regulatory pathway, and manufacturing process are and why biosimilars can be trusted ,” says Engert.

Technology-driven affordability

Given the costly barriers to commercialization and the subsequent lack of biosimilar competition on the market, biosimilars do not offer the same average 85 percent price reduction (vs innovators) that generics currently offer.

Affordability plays a roll patient and payer acceptance, and some argue that biosimilars are not delivering low enough price reductions. In a recent analysis, Back Bay Life Science Advisors polled U.S. payers representing large national health plans, and found they were reluctant to switch from the innovator therapy because they were not yet seeing the anticipated 30 to 40 percent reduction relative to the net price of corresponding biologics.5

As equipment vendors evolve to meet changing industry needs, new technologies and techniques that help maximize the efficiency of production labor and equipment can help biosimilar manufacturers save on manufacturing costs.

Univercells, a technology company delivering novel biomanufacturing platforms, offers up one potential solution. The company claims that their technologies can dramatically reduce Cost of Goods, thus enabling manufacturers to offer biosimilar products at competitive prices while still securing high margins.

“Our smart facilities are engineered to enable dramatic reductions in capital investment and CoG without compromising product quality,” says

Tania Pereira Chilima, product manager, Univercells. “These reductions are achieved through process intensification, process chaining and automation, as well as through the implementation single-use systems which reduces the utilities consumption.”

Originally backed by an investment from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Univercells has a core focus on high-quality biologics for small to medium-size markets but the technology could provide relief fit for biosimilar manufacturers looking to keep costs down.

Keeping momentum

Despite the pervasive uncertainty that plagues the U.S. biosimilar market, the market remains attractive. As novel biologic prices continue to rise, even when sold in small batches and at a discount, biosimilars have the potential to generate significantly high returns for drugmakers who learn to navigate the landscape.

For biosimilars, the commercialization has proven to be just as complex as development.

“Because of the complexity of the science and the nascence of the regularly pathway, people were understandably entirely focused the development, regulatory and manufacturing sides. Now it’s time for everyone to push it to the next level and really understand the systemic versus unique risks comprehensively across all the functions — in particular, addressing the commercialization challenges,” says Engert.

There is still work to be done on the regulatory side and the legislative side, and education of patients, physicians and payers should be ongoing. Beyond that, drugmakers who apply the same kind of rigor that they applied to develop and regulatory issues to commercialization, taking the time to understand what incentives are in place for each stakeholder and choosing their channels wisely, stand a better chance of success.

Biosimilars represent a significant catalyst for change in the healthcare industry, offering market-based, competitive solution to the issue of rising drug costs. If realized, they have the potential to create a more sustainable system, which could ultimately help more patients receive better care.

“Biosimilars are a strategic imperative: something that requires focus, not just for the good of these companies to find substantial returns, but also to help create balance between the need for innovation and the need for a sustainable solution from a cost perspective,” concludes Engert.

About the Author

Karen P. Langhauser

Chief Content Director, Pharma Manufacturing

Karen currently serves as Pharma Manufacturing's chief content director.

Now having dedicated her entire career to b2b journalism, Karen got her start writing for Food Manufacturing magazine. She made the decision to trade food for drugs in 2013, when she joined Putman Media as the digital content manager for Pharma Manufacturing, later taking the helm on the brand in 2016.

As an award-winning journalist with 20+ years experience writing in the manufacturing space, Karen passionately believes that b2b content does not have to suck. As the content director, her ongoing mission has been to keep Pharma Manufacturing's editorial look, tone and content fresh and accessible.

Karen graduated with honors from Bucknell University, where she majored in English and played Division 1 softball for the Bison. Happily living in NJ's famed Asbury Park, Karen is a retired Garden State Rollergirl, known to the roller derby community as the 'Predator-in-Chief.'