Supply chain collaboration is underleveraged in the pharma industry. Although other sectors, such as consumer and retail, have put more focus on managing their supply chain, most of Pharma’s collaboration efforts still center on the commercial side. However, as the results of a recent joint ECR/McKinsey collaboration survey indicate, in the near future industry executives anticipate an increasing focus on supply chain collaboration in such areas as demand planning and fulfillment or supply chain flows and processes. Given the dynamics of client discussions in health care, we expect this shift to take place in pharma as well.

Today, less than half of the value chain in pharma is externalized, which is considerably lower than in the automotive or aerospace industries where it reaches 70 to 80 percent. An increasing focus on contract manufacturing, however, can be expected to drive the need for more advanced cooperation models. This trend will be further accentuated by regulatory actions, such as the May 2013 U.S. FDA guidance for the pharma industry on quality practices in contract manufacturing arrangements.

The consumer and retail, automotive, and high-tech industries have already seen examples of successful collaboration efforts, albeit each of them in its own distinct focus area:

• Consumer and retail: large-scale supply chain information sharing.

• Automotive: multi-tier demand and supply transparency.

• High tech: integrated planning, electronics manufacturers have successfully implemented integrated planning — spanning the entire supply chain.

Many large pharma companies embarked on creating supplier network platforms in the area of supply chain information sharing, but both the depth of data exchange and the level of integration remain low. Better examples of supplier collaboration have been seen with contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) established as pharmaceutical plant spin-offs. Demand-and-supply transparency is also weak within the sector. While principles underlying supply chain collaboration in other industries are applicable to pharma, additional constraints are imposed on the industry by the uniqueness of the pharma supply chain. These constraints are numerous and start with pharma’s stringent regulatory requirements that impose strict product availability requirements, long lead times associated with switching suppliers, and high complexity in change management because master data are extensive; they must be absolutely accurate at all times.

CONSTRAINTS AND COMPLEXITY

Most understand pharma supply chain networks are increasingly complex. Pharma’s specialized supplier base — focusing on concrete therapeutic areas as well as particular production steps, combined with a fragmented network of manufacturing plants for different purposes (e.g., formulation, bulk, primary packaging, secondary/tertiary packaging for market access) — fuels complexity.

SKU complexity is becoming more pronounced, with the average number of SKUs per packaging line increasing. Different technologies, dosage forms, packaging sizes, and numerous country-specific requirements are just a few parameters driving SKU complexity. The growing trend toward more personalized medicine has become a contributing factor as well.

As opposed to the consumer and retail or high-tech sectors, where manufacturers most often deliver to retail distribution centers, the immediate Pharma customers are predominantly wholesalers. These intermediaries effectively impose another layer of uncertainty on the supply chain, making demand forecasting and logistics optimization more challenging.

Long lead times in switching suppliers or strict product availability requirements, for example, are all the more reason to improve collaboration. The high product availability expectations that put increased pressure on the customer service levels would also be substantially improved via collaboration. In sum, we see no reason why supply chain collaboration in pharma could not be as successful as in other industries once prerequisites are in place.

THREE DISTINCT OPTIONS FOR PHARMA

The primary example of peer collaboration is PharmLog in Germany, a joint venture set up by six major Pharma companies. Joint venture activities include a wide range of shared distribution and warehousing functions including order and stock control, receiving and storage, picking and packaging, batch control, repackaging, etc.

CASE FOR SUPPLY CHAIN COLLABORATION

The value of supply chain collaboration already demonstrated in other industries ranges from working capital improvement and cost reduction to decreased spending and higher sales. It also fosters revenue growth through better on-shelf availability and flexibility to address demand changes. Collaboration can generally have a positive impact on a wide range of supply chain performance metrics, including service level (supplier and customer), stockouts, order changes, forecast accuracy, production planning accuracy, lead time, flexibility and agility.

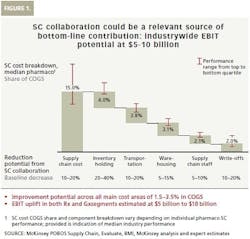

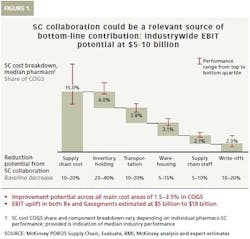

While improvement of service level or product availability generates significant value on its own, the financial benefit of collaboration can be expected from reducing the five main supply chain cost buckets: inventory holding, transportation, warehousing, supply chain staff and write-offs (See Figure 1).

COSTS

Pharma supply chain costs vary depending on individual supply chain performance. McKinsey estimates that the full reduction potential from supply chain collaboration across all main cost buckets could achieve around 1.5 to 3.5 percent COGS improvement. This is especially relevant for generics players that have a significantly higher cost share. Results of this magnitude require that prerequisites are in place, the right approach is chosen, and the most critical levers are engaged. Given today’s industry size of about $900 billion in the combined originator (Rx) and Gx segments, as well as the current cost structure, the industry-wide potential impact of supply chain collaboration amounts to $5 billion to $10 billion in earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) improvement.

Following a successful procurement transformation, a global pharma company launched a supplier collaboration program to deliver value-driven savings beyond pure price reduction. Several supplier pilots were launched, with the following outcomes: 50 percent reduction of inventory, 15 percent European transport cost decrease, 17 percent packaging-material cost reduction, and 20 percent capacity increase for filling operations. Success was attributed to the careful design of program architecture and approach, thoughtful selection of the right suppliers for the pilots, dedication of company resources to supplier capability building, and the drive for cross-functional collaboration.

As mentioned earlier, full-scale customer collaboration programs have not taken off in the pharma industry. One recent noteworthy initiative is the launch of a global forecasting excellence program by a major Gx player, which includes a joint forecasting pilot with a select customer. The impact is yet to be shown.

HOW TO MAKE COLLABORATION INITIATIVES WORK

To increase the odds of achieving significant benefit, it is crucial to ensure, prior to launching an initiative, that the prerequisites for collaboration are in place and that the right approach is being applied. There are five critical prerequisites that management should consider before launching collaboration efforts.

1. Commitment and resources: Collaboration should be positioned as a strategic priority with explicit senior-level commitment and accountability from partners. There must be available resources to form a joint, dedicated supply chain team, with involvement of other functions.

2. Data exchange mechanism: The sharing mechanism should be realized by setting up an independent clean team to ensure confidentiality. In later stages, it should be transformed into the IT interface with clear governance rules.

3. Value-sharing scheme: The sharing of benefits, costs and risks should be clearly defined up front. This is particularly true for situations when value cannot be directly attributed to the collaboration initiative or when a performance metric improvement is difficult to translate into the financial equivalent.

4. Performance tracking: Performance of the collaboration initiative should be tracked via jointly determined metrics with clear measurement processes that are well understood and transparent to partners. The performance-tracking system should feed the value-sharing scheme.

5. Program architecture: While the launch of a collaboration program can represent several pilots with suppliers, customers and peers, in the end there must be a structured project approach to each collaboration initiative.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Knut Alicke ([email protected]) is a master expert in the Stuttgart office. Denis Fedoryaev ([email protected]) is an associate principal in the Copenhagen office. Patrick Oster ([email protected]) is an analyst in the Wroclaw office.