Like all industries, pharma is riding the green wave. (See “Pharma’s Green Evolution”.) Many drug manufacturers, in fact, are now models of environmental stewardship. They’ve picked the low-hanging fruit on a facility level (optimizing HVAC, using high-efficiency lighting, for instance), and are now zeroing in on their manufacturing processes—looking to reduce materials consumed and waste produced, cut cycle times and thus energy and equipment usage, and optimize processes, not only to get drugs to market sooner but to reduce the overall environmental impact of development and commercial manufacture.

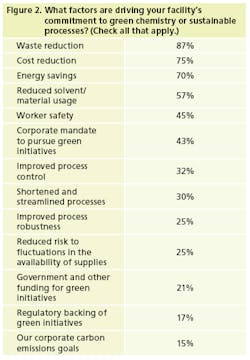

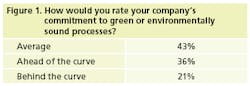

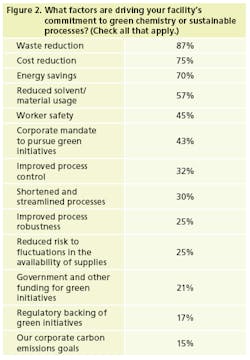

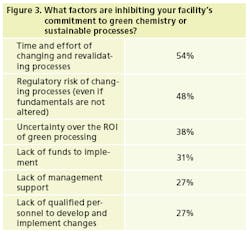

We surveyed a small segment of our readers (just over 50) to gauge the industry’s efforts to make its processes less wasteful and more environmentally friendly. We also wanted to discover what role Process Analytical Technologies (PAT) and Quality by Design might be playing in these efforts. Here is a summary of what we found, and what expert observers are seeing.

Competitive Advantage

To no surprise, waste and cost reduction, along with energy savings, are the most significant drivers of manufacturers’ efforts to green their processes (Figure 2). The other items on the list, of course, speak to those goals as well.

Green and sustainable processes present a competitive advantage, says Mike Whaley, Allergan’s senior director for Environmental Health and Safety. They represent opportunities for cost savings, additional revenues, and cost avoidance, he says. As such, sustainable processes win favor with investors and customers.

Allergan’s “improvements in product design and processing complement one another to achieve cost savings,” Whaley says. “In particular, a more efficient process results in greater production capacity, easier and more predictable manufacturing, less waste generated, and cost savings.”

If green is good for business, why isn’t everyone pursuing processes that use fewer solvents or less water, produce less waste, or consume less energy? Validation and regulatory concerns are the top obstacles, our survey respondents said (Figure 3). Manufacturers may pay lip service to changing their processes for the better, “but the body language tells you that they are afraid of the regulatory risk,” says Jack Carroll, managing partner of Cadrai Technology Group.

A lack of time and qualified people is also an understandable concern, Carroll says. Operations management may see the benefit of greening manufacturing processes, but do the benefits outweigh the opportunity costs of not pursuing other projects, and having your best people working on those other projects?

Leveraging PAT

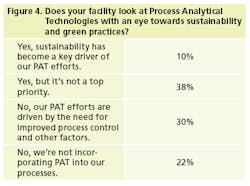

Manufacturers are just beginning to equate PAT with reducing the environmental impact of processes. Ten percent of survey respondents said that sustainability had become a key driver of their PAT efforts, while approximately half said that they look at PAT with an eye towards sustainability or green practices (Figure 4). As one of our respondents said, “Process control is environmental control.”

GSK may be ahead of the curve in this area. Darryl Ertl, manager of GlaxoSmithKline’s PAT group in the Research Triangle Park, has seen a dramatic shift within his own company in just the last six months in terms of the acceptance of PAT as a vehicle for sustainability, and cost savings. Whereas in the past PAT was equated with process control, and implemented primarily ad hoc in commercial manufacturing, it has recently moved up in status, and moved upstream in the development cycle.

GSK’s pilot plants, in looking to reduce cycle times, save energy, and cut costs, have gravitated towards PAT. “We used to have to push these initiatives,” Ertl says, “but now the pilot plants are saying, ‘We want to do these things. We can save a significant amount of money.’ It’s a pull vs. push mentality.”

Just this spring, GSK established a worldwide team, with one representative at each pilot facility, to promote the use of PAT to determine the endpoints of drying operations. NIR and mass spectrometry are the two specific technologies being leveraged. A catalyst for the team, Ertl says, was preliminary data out of GSK’s Cork, Ireland facility that illustrated clear and significant benefits of reducing cycle time for several key late-phase molecules.

That PAT can support corporate environmental objectives means that it will continue to gain favor as a mechanism for sustainability. “It doesn’t have to be a big bang,” Ertl says. Small and incremental improvements in developing green and sustainable processes will reap sizeable benefits in the long run.

QbD: Green by Nature?

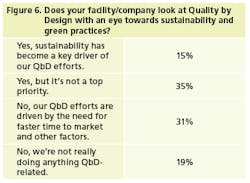

Ertl, interestingly, does not see Quality by Design as going hand in hand with sustainability. QbD’s guiding premise (at least how it is practiced in industry) is to get drugs to market faster, with greater quality, which can come at the expense of efforts to reduce waste, use fewer solvents, and so on.

David Ager, principal scientist for DSM Pharmaceuticals, also questions whether QbD directly supports green practices. As a CMO, DSM is under pressure from the customer to be “first time right,” Ager says. “QbD helps us in this effort, especially when a candidate moves down the development pipeline. But QbD and the sustainability considerations have to be taken as two different variables, and for drugs, quality is the dominant factor.”

The savings and cost reductions derived from designing green processes “usually result in a better process but this may not be more robust or streamlined,” Ager continues. “There are examples where a greener process uses an extra step compared with the original route; the two-step process giving a higher overall yield and allowing a catalytic step rather than use of a stoichiometric reagent. The different parameters given in the responses are interdependent and, in many cases, process specific.”

In contrast, Julie Manley, president of the sustainability consulting firm Guiding Green, LLC, sees an organic connection between both PAT and QbD and sustainability.

Metrics such as process mass intensity, or PMI, can be a key in helping manufacturers to monitor and reduce the impact of their processes, and Manley believes that when manufacturers say they are using environmental metrics to measure their processes, it may misrepresent how well such metrics are understood and used for improvements. Manufacturers in the past may have measured the environmental impact of their processes for compliance reasons, she suggests, rather than for reasons of sustainability and reduced impact. Recognizing the culture shift to incorporate non-regulatory characteristics as critical attributes, Manley believes incorporating sustainability criteria as critical process parameters is still a newer concept.

Both PAT and QbD have obvious potential for greening processes, she continues, and are well aligned with accepted principles of green chemistry (see box below). It should also be noted that they are widely viewed as congruent with continuous processing and the use of microreactor technologies, which are starting to make an impact in the industry and helping manufacturers improve the environmental profile of their processes.

Bio’s Big Chance

Biotech processes stand to benefit tremendously from the current green revolution. Carroll of Cadrai Technology has noticed that in his conversations with manufacturers around the globe, it’s usually only the bio folks who bring up green and sustainable processing, because the payoff—from a cost or environmental standpoint—is much clearer. Bioprocesses are by nature slow and complex, and thus it makes sense to leverage QbD principles to design a faster, more robust (and presumably more sustainable) process.

Specific PAT applications also have rich potential in biopharma, he says. “PAT can be used to wind down a fermentation process two days early, and there’s some serious money involved in that”—namely, because of the tremendous energy savings. The larger the equipment, the more obvious the green benefit is, says Carroll, and they don’t come much larger than, say, a 20,000-liter bioreactor.

Playing the Green Card

Several of our survey respondents indicated that green chemistry or process optimization projects have been derailed by the recent economic recession. One said that, in the wake of the crisis, all that mattered was product safety and business contingency.

But aren’t greener processes always good for business (not to mention safety)? It depends on how you look at it, says GSK’s Ertl. From a business standpoint, you want to make molecules quickly and cheaply. Going green may make a process more expensive, Ertl notes, or sacrifice yield or quality, as happens sometimes when moving to processes using aqueous-based solutions.

“These are the balancing acts that scientists do every day,” he notes. At GSK, there is a strong top-down mandate (starting with CEO Andrew Witty) to tip that balance toward environmental responsibility.

The potential of PAT and QbD to pay green dividends is real, says Jason Kamm, principal with Tunnell Consulting, Inc., and this potential is not lost on operations managers and project leaders. It’s hard enough to justify expenditures and time commitments for PAT and QbD programs, he says, so playing the environmental card is one more way to get upper management support for such initiatives.

From a PAT standpoint, new testing and analytical technologies have enabled energy saving and other benefits that might not have been realized in the past, Kamm says. “They don’t add up to huge dollar savings, but at least they’re headed in the right direction” towards lower costs and greener and more sustainable processes, he says.

It’s imperative, says Kamm, to keep the environmental consequences of processing decisions from being an afterthought. “You should always think about how [PAT/QbD and sustainability initiatives] fit together,” he says, “There are a lot of synergies to be realized.”

If anything, PAT, and to a greater degree, Quality by Design, present industry with a mindset that is open to change. QbD, says Kamm, changes the regulatory dynamic that in the past might have stifled creativity and process improvements. When a manufacturer starts to launch QbD projects, “a lot more of the improvement ideas can be left on the table,” and a lot of these ideas will aid more environmentally sustainable manufacturing.

|

Filling the Green Chemistry Toolbox One of the leading proponents of the green chemistry movement is the American Chemical Society, namely its Green Chemistry Institute’s Green Chemistry Roundtable. The Roundtable, founded in 2006, currently has 14 members, and has recently opened up membership to contract researchers and manufacturers, as well as generics manufacturers. The drug industry, a leader in green chemistry, is yet just beginning to scratch the surface on realizing the benefits of green chemistry, says Julie Manley, president of sustainability consulting firm Guiding Green, LLC, and who coordinates and manages Roundtable activity. “To be a greener alternative, a process should not only be less hazardous, it should have an equivalent or better economic profile, and have equal or better performance,” she says. One of the greatest challenges in improving green chemistry across the industry is a dearth of green alternatives, Manley says. Greener solvents are becoming available as the market for them increases, but there is often less collective knowledge regarding how to green processes. While the industry has had its successes, “the opportunity to green processes outweighs the accomplishments,” she says. “A process can only be as green as the tools that you use and your innovation allows,” Manley adds. One of the first initiatives of the GCI Roundtable was to help manufacturers identify a dozen commonly used pharmaceutical reactions that were ripe for benefiting from green principles. The effort to promote improvements to these processes and to help manufacturers fill their “Green Chemistry Toolbox” is ongoing. Industry collaboration will be critical in developing the toolbox. A promising sign, says Manley: Despite the struggling economy, the Roundtable, with membership fees up to $25,000 per year, picked up five new members in 2009. Manley sees companies increasing the resources and attention that they devote to green chemistry initiatives, but acknowledges that some companies are still in the “exploratory phase” of their efforts. |