Over the last decade, it seems that there have been a steadily increasing number of pharmaceutical products recalled, either by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or voluntarily recalled by their manufacturers. Offenses have ranged from the egregious (potential glass shards and incorrect product in package) to the mundane, less patient-threatening (slight “musky” odor, slight errors on the label or improper package inserts), but all have constituted “adulteration.” Speaking at PhRMA’s annual conference in Washington, D.C., FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg highlighted recent reasons for concern that quality standards are not being adhered to, as well as the agency’s renewed focus on enforcing those standards: “We are … trying to really reshape some of how we address the quality issue, to try to incentivize better practice and more accountability around quality … And I think this is the time when we need to be recommitting to it.”

In response to Commissioner Hamburg, the question at this point becomes: “How does one increase and enforce both compliance and quality in the industry?” Perhaps this sounds either naïve or even overly ambitious, but ultimately the dialogue must start. Consider the following observations based on more than 40 years of experience working in the industry:

There needs to be an overall atmosphere where the Board/Executive management supports quality goals as much or more than financial goals. General Motors has been in the news recently because the company appeared to care more for profits than the lives of their customers. Media reports point to how GM’s internal culture led executive managers and others in disparate operational and legal departments shuffle and silo the problem without actually working to resolve it in an ethical, straightforward manner. One can only imagine the memos calling for “better data,” or “another study,” or waiting for some “other” department or administrator to provide more information. Add to this purposeful obfuscation by some, then buck passing and CYA behavior from others, and it becomes less hard to imagine how the company sacrificed its reputation for the sake of first green-lighting a potentially problematic component design (created under tremendous pressure on the supplier to squeeze every cent of cost they could out of the part to meet GM purchasing’s price target) and then delaying a recall on a part that cost 56 cents.

When a company’s executive management makes it excessively clear that quality has the highest priority and then acts on that principle (investment, training, rewards, warnings, dismissals, etc.), only then will there be a chance for the rank and file (middle managers, directors and department heads) to deliver compliance and consistent quality to consumers. So often, CFOs see things in black and white; that is, numbers on paper, but seem not to perceive the negative ripple effect harsh cost-containment financial policy can have on corporate culture and ethical behavior. It’s likely rare that a Pharma manager blatantly told an employee to perform an illegal or unsafe act. The message is usually more subtle, i.e., “We have a cost containment goal” or “Remember, your raise is based on the number of units made/assayed/packaged each year.” When the manager asks for results, does he/she phrase it as, “When will you finish the assays on that lot?” or, more likely, “When will you pass that lot?” How he/she asks for results gives the worker a subtle goad to move more quickly (and get the “right answer”), no matter what.

What is needed is a change to an atmosphere of “Do the best you can, no matter what the answer.” Then, and only then, will the workers feel comfortable to follow rules and not a manager’s whims. Would it hurt to have a manager’s year-end evaluation acknowledge exemplary compliance performance and proper adherence to cGMPs along with production and other output targets?

EDUCATION

It is hard enough to keep employees adequately “trained,” especially if quality or compliance regimes are confusing or contradictory, guided by SOPs so numerous, poorly understood and badly administered that the only “standard” procedure is to work around them. Hard to believe? Several years back, a major company came under a consent decree for, among other offenses, “excessive and contradictory” SOPs (Some 35,000 were identified). No amount of training or training investment will ever truly ensure compliance when SOPs are nearly too numerous to count and contradict one another.

In addition, no human Quality Assurance (QA) or Compliance officer could possibly keep up with the paperwork for that may SOPs. It’s more likely that when faced with overwhelming workload (paperwork and associated administrative tasks), work that’s rarely checked by any QA authority, the human thing to do is prioritize and assign a rough hierarchy to various SOP-related tasks so as to avoid the “appearance” of non-compliance — such behavior often leads to a 483 observance. In addition, when faced with contradictory SOPs, one version has to lead to either product failure or a non-compliance citation, so what does the operator do (especially when there is a tight production schedule)?

PERSONNEL AND WORKFLOW

In the age of contraction or downsizing and “lean,” apparently the prevalent business model driving operational resource planning, adding headcount or training existing personnel to be fluent in modern analysis methodology or multivariate analyses, is likely out of the question.

In general, just implementing a standard GMP-based process for a solid-dose product requires a number of procedural steps. With this much complexity (granulation, drying, blending, compaction, coating and packaging) involved in a step-wise process (that has not changed all that much over the last 50 years), each arrow may represent a large number of steps, each time-consuming and often tedious … and all of which must be documented. The time between steps can be as long as days or even weeks, adding to the cost and time of production … all of which may lower quality.

SHEER COMPLEXITY

The sheer complexity of the number of steps (and, often multiple venues) involved often leads to interactive, but not integrated SOPs between several groups (jurisdictions). For example, when a warehouse operator secures a fiber drum of raw materials for a QC technician to take samples, which group is responsible for noting the sample has been moved from production? QC? Warehouse operator? QA? Further, where is the document stored and who then reviews it? Another question begs asking: If the operator is to (representatively) sample the finished product or intermediates, and it is stored in multiple containers, does he or she need (yet another) SOP on how and where to sample? And, for final assay, how representative are, say, the 20, 30 or more tablets taken from 20 to 30 fiber drums?

Pseudo PAT: more measurements, but no integration, thus still long waits between steps.

Actual PAT: continuous flow, with each step smoothly dovetailing into the next.

More modest Pharma companies tend not to have the deep capital reserves necessary to keep up with advances in control and automation technology. The first attempts at placing measurement devices along the process stream (in the name of PAT) were intended merely to take measurements without using these data to control process. In other words, PAT was not achieved. The process analyzers merely churned out more numbers to store for later analysis. Figure 1 shows that the work flow changes somewhat, but is barely improved when instruments are added, but not integrated.LET’S GET INTEGRATED

As process steps become integrated using a central controller, where the intermediate product flows from step one to step two as a smooth flow (based on instrument readings), two things happen. First, the information flow now resembles Figure 2, where all data are both archived and acted upon instantaneously. Second, the operator is taken out of much of the process. Since data is automatically logged, there are no transcription errors and fewer problems for QA to worry about (or write yet another SOP to manage it). When the intermediate product is measured automatically, samples need not be taken, logged, assayed, etc., at points where each step is susceptible to errors and requires more SOPs — ones likely to be misunderstood or ignored. The smaller number of SOPs and operator interventions will almost immediately cut down on the need for complicated written procedures.

An integrated PAT system allows materials to flow from the dispensary through the processing steps to the packaging line without being taken to a storage facility. This will not only increase speed of production, but generate more process data as well. We now know and can prove that step 1 is good before the material moves to step 2. The difference is that several days/weeks have been reduced to several seconds. The results are automatically stored (taking decisions out of human hands) and, more to the point the company is following cGMPs’ recommendation of proper (my emphasis) in-process testing and a statistically significant number of final dosage forms (not the 20 out of 5,000,000 units as most now assay).

As any relatively aware person in the Pharma industry understands, there are consequences for producing and selling poor-quality products. However, such consequences are usually financial and seldom directly affect managers, the ones setting a poor example for those he or she supervises. Unless and until penalties reach further down the corporate ladder, the game of “beating the odds” is likely to continue. When, for example, there are six or seven state troopers patrolling 200-300 miles of an interstate, most people play the odds and speed, assuming they won’t get caught. Some Pharma executives may be playing the same game — if the penalties get high enough, the incentives to cheat diminish accordingly.

FUTURE TRENDS

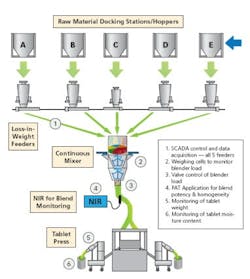

Spoiler alert: The end game for PAT (and of course, QbD) is continuous manufacturing (CM). Under the paradigm of CM, production is performed on small, development-sized mini-batches, each being controlled to be exactly the same as the last (see Figure 3). Compare that to the “traditional” manner of product development through which production is a step-by-step development, with each step scaling up in size from development through pilot plant to production.

Continuous processing with minimum human intervention and multiple controls for each step.

Unfortunately, each step/size demands different equipment, each with its own equipment and operating procedures. From an operational standpoint, that means a large number of operating and cleaning procedures. When one mixes in so many operating procedures and venues, operations are just asking for violations.The complexity and number of people involved almost assures there will be paperwork errors, if not actual procedural errors. When the development, pilot and production size batches are the same, the chance for quality and compliance errors are greatly diminished. When lot-after-lot can be manufactured the same every time, the product, itself, can be continuously improved and consistently produced.

From a training standpoint, a constant level of equipment will make it easier for operators to become proficient in their jobs and not have so many procedures to follow (or misread or outright ignore). With fewer types of equipment to learn to operate and clean, fewer mistakes will be made, leading, again, to higher standards of quality. So if we are aiming for the highest quality and tightest compliance in the Pharma industry, CM will be the end game.