Modular Approach to Water Processing Control & Automation

Almost anyone can recognize the practicality associated with the concept of modularity. To the many engineers who busy themselves designing, engineering and constructing complex pharma processing systems, the idea of managing such complexity by breaking it down into standardized subsystems and components is a well understood and pragmatic approach to system design. According to Festo, such is the case with automation and control. Modular systems, say Festo, speed up the design and configuration of automated processes, lower overall costs, and make a process like water filtration more flexible and therefore better at adapting to new operational requirements and responsive to market demands.

"This approach represents a fundamental shift in the design and engineering requirements for water filtration applications," says Craig Correia, head of Process Automation at Festo. "Flexibility is achieved through consistent modularization, i.e., dividing a complete plant into functional units. "These functional modules are combined to create the automated filtration system. Water filtration plants built on these functional elements can be extended almost indefinitely by adding modules, thus enabling immediate adaptation to market and filtration requirements."

According to Festo, the design and engineering of a given process is precisely tailored to the respective task, whether for producing a specific product in X units per time unit or to generate the throughput of a specific substance in X quantity per time unit. As a whole, the mechanical design of the plant is geared toward meeting specifications and assuring the required performance data over its projected lifecycle.

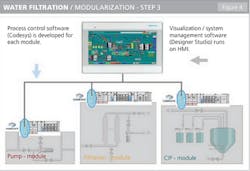

Correa explains that the corresponding automation is configured using management systems comprised of process-specific (control) components, operating and monitoring stations as well as engineering stations. The entire process is centrally controlled by a single management system.

SPEED TO MARKET IMPERATIVE DRIVES DEMAND FOR FLEXIBILITY

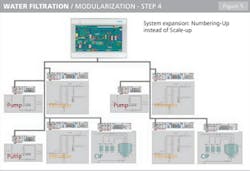

Festo maintains that markets are increasingly demanding shorter product development cycles, particularly in the small and large molecule pharmaceutical industry segments. The result? Correa says it has prompted a fundamental shift in the design and engineering requirements for process plants of all types including water filtration. He explains the necessary flexibility is something that is available now and achieved through consistent modularization, that is dividing a complete plant into its functional units. "These production modules can be combined to produce specific process plants," says Correa, "which can be extended almost indefinitely by adding modules, thus enabling immediate adaptation to market and production requirements. Capacity is increased by numbering up instead of scaling up."

The ability to temporarily sideline production modules from the current production process, notes Correa, is another aspect of the concept's inherent flexibility that will have a positive impact on operations and managing maintenance, equipment change-outs and other similar tasks.

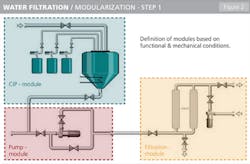

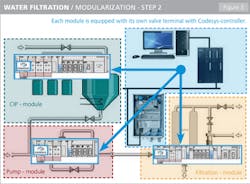

Most water filtration plant designs include pipes, pumps, valves, tanks, filter modules and sensors. Correa says the required components for actuating the field devices are installed in a control cabinet. Valve terminals, such as a remote I/O system with integrated pneumatic section, are connected to a central controller with visualization (management system) via a fieldbus. Plants of this type, he says, can be easily modularized by breaking down the process into subprocesses and defining a module for each sub-process with all the mechanical and automation components required for stand alone operation. For a water/waste water plant, key or critical modules would likely include its pumps, filtration modules and the clean-in-place system.

Builders find themselves engineering a skid based on a customer's spec," says Correa. "So each one is different. They might be able to cut and paste previous designs, like the control cabinet or skid layout, and just scale it. But this adds to lead time, and as a result adds cost." In an ideal world, explains Correa, builders would have a design that is scalable, not by changing the design, but by plugging a few modules in parallel. "Because even when they change the design," Carrea notes, "they have to purchase a fabricated frame, etc., which is unique. The concept here, which some OEMs are doing, is to create smaller solutions which can be mounted easily in parallel as more throughput is needed and have specific functions for each. When the spec specifies the volume and the filtration levels, they can expand both the capacity (parallel modules) and filtration types (modules in series)."

Plants of this type can be easily modularized by breaking down the process into subprocesses and defining a module for each subprocess with all the mechanical and automation components required for standalone operation.

- Modular automation and control supports a plant engineer's pursuit of process modularity where any configuration to be assembled can be by adding modules of identical construction and function (See Figure 4), thus allowing a numbering up expansion strategy instead of scaling up (See Figure 5).

- Modules are precisely defined units with clear functionality.

- Modules are equipped with their specific application software, which reduces the respective software complexity.

- Modules are easy to change/extend in terms of their (clear) functionality.

- Modules can be manufactured in small series and fully tested prior to delivery.

- Customized complete systems are assembled from different modules of identical construction (numbering up).

- Modules are programmed using CODESYS (as per IEC 61131-3, no license costs), i.e., independence when selecting the automation hardware.