2006 Job Satisfaction and Salary Survey: Are You Boxed In?

By Paul Thomas, Managing Editor

It’s a time of contradictions for pharmaceutical manufacturing professionals. On the one hand, the job market is hot — for researchers, engineers, Lean and Six Sigma black belts, compliance specialists, and those at the top of their game. Biotech and new plant construction are strong, and the competition for top specialists is fiercer than ever. At the same time, wholesale layoffs continue, and U.S. jobs are steadily trickling overseas.

| For a graphic detailing the demographics of our survey respondents, go to the end of this article. |

The divide between the pharmaceutical manufacturing haves and have-nots is widening. Those with marketable and transferable skills — including soft skills such as communication and an appreciation for diversity — and those who manage their careers aggressively are moving up and on; workers who lack transferable skills or have failed to stay current of the latest technologies face an uncertain future.

Manufacturers are taking a pragmatic approach, with many assuming that new hires will only stay for three to five years. But while they’re there, employers are doing their best to keep star employees happy. “Employees are expecting more from their employers now than they ever have,” says Jeff Harvey, AstraZeneca’s U.S. recruiting director. “They want to be challenged and developed, and expect it earlier in their careers. And if they aren’t [getting what they expect], they’re moving on.”

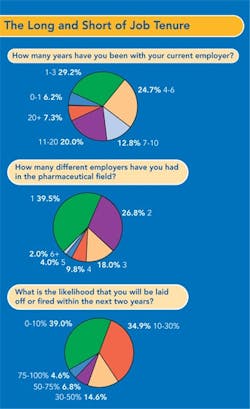

But these are the elite. The average pharmaceutical manufacturing staffer is less sure of his or her livelihood than ever before. More than 55% of the 500 people who responded to this year’s annual job satisfaction and salary survey are concerned about job security (see "The Long and Short of Job Tenure" graphic, below), up from 44.4% last year. “There’s no such thing as a permanent job any more,” says Shannon Brannagan, director of KForce, a scientific staffing firm based in Tampa, Fla. “Even when you’re hired for a new full-time position, there’s concern.”

Some of those who responded to this year’s survey already know the writing’s on the wall, and that their jobs will soon be moving to another country. “Our owners have announced that they will take all or most of our manufacturing to Europe by 2007,” one of you said. “I fully expect to be laid off by this time next year.” Roughly 35% of you felt that there was a fair chance (between 10% and 30% possibility) that you would be laid off within the next two years (see "The Long and Short of Job Tenure" graphic, above).

To hear some of you tell it, women and minorities have little to be concerned about. They’re the darlings of recruiters and headhunters who represent firms that have mandates to increase workforce diversity. “The issue now is reverse discrimination,” one of you wrote. “Minorities and women have all the opportunities.”

Most women and minorities in our survey would beg to differ. They may have broken through the glass ceiling, but find that life within the plant has its hardships, and that their salaries are not yet on a par with those of white males. Our survey numbers bear this out (see "Money Talk" graphic, below). “Discrimination only comes from the group that holds power,” says Henry Ragin, an African American manufacturing supervisor with Wyeth Vaccines in Sanford, N.C. “If most of the executives and managers in a plant are black and female, then white men may have a gripe.”

In the end, the industry today holds threats and opportunities for all. Career success may come down to how you perceive your lot, and take action to improve it. “There are real issues out there, but perceptions can become reality,” says Leslie Alexandre, Ph.D., director of the North Carolina Biotech Center, who speaks regularly to drug industry professionals about their careers. “There is no complete job security any more, so you have to look for your opportunities. There’s a lot to be said for strong generalists who can connect the dots.”

Targeting the chosen few

If you have a few years of experience in the industry, and useful skills — a knack for IT or validation, say — you may already be on another drug company’s radar screen and not even know it. “The more sophisticated companies have realized that they need more people in the hiring pipeline, to be on the bench when the team needs them, so to speak,” says Richard Kneece, CEO of Massachusetts Technology Corp. (Allston, Mass.), which operates Internet career sites hireRx and hireBio. “They know in advance the people that they’d like to hire.”

Human resources departments and hiring managers are beating the bushes for qualified candidates, combing conferences and networking events, mining membership lists of professional organizations, all in pursuit of top talent. “There’s more targeting of passive candidates than there ever has been,” says AstraZeneca’s Harvey. “We know who some of those folks are that we want to talk to.”

Which begs the question of what fair play is in this day and age. “We will never openly recruit from other pharmaceutical companies,” Harvey says. “But if we start talking to someone who has the right background, and we find out later she works for Pfizer, we’re certainly not going to stop talking to her.”

Loyalty, 2006

More than 60% of respondents indicated that they had worked for two or more pharmaceutical companies in their careers (see "The Long and Short of Job Tenure" graphic, above). What may be more telling, however, is that more than 30% of the twenty-somethings we surveyed had already had two or more employers.

Job-hopping is commonplace, and the career-minded are more willing to take temporary or even part-time work. The pharma and biotech industries are large consumers of contract staffing, says Chris Jock, VP and GM of global operations for Kelly Scientific Resources (Troy, Mich.). Companies are often reluctant to invest too much in untested workers who likely won’t stick around for more than a few years anyway. “The younger generation is aware of this, and sees each position as a platform or launching pad,” Jock says. They know that the path to the right job might take three, four or more stops.

Veteran pharmaceutical workers need to take this to heart, says Kneece. “It’s not an industry that has tended to have a lot of job jumpers,” he says. “There are a lot of people that are very employable but just don’t realize it.” More than ever, the best jobs are going to those who promote themselves and take risks, he says.

Is there such a thing as loyalty anymore? “Employees are loyal to themselves and the friends they make in the industry,” says KForce’s Brannagan. “They create alliances.” From their employer, they expect not just a paycheck but also career development and a supportive environment. This could be in the form of major initiatives such as cross-training or shifting top employees among departments and sites to keep them motivated, as well as offering up unique perks such as hiring Elton John to perform at a company outing, as Genentech has done.

Kneece sums up the employment contract this way: “I’ll work hard this week for a paycheck, and you need to give me the skills that will allow me to move on if I need to.” Good companies will provide those skills, he says, and expect very little in return. More often than not, the employees that they challenge and develop will stay on longer, seeing the career benefit in doing so.

Oddly, it is younger workers who feel the most underpaid and underappreciated. Nearly 65% of those in their twenties that we surveyed feel that they are not adequately compensated for their experience and skills (see "Money Talk" graphic, above).

Not your father’s HR

To cope with a mobile, hard-to-please workforce, human resources departments are rethinking their standard practices. “HR departments are becoming more sophisticated and specialized in skills,” says Brannagan of KForce. “They’re becoming experts in people and jobs in specific industry sectors.”

For AstraZeneca, there is caution in chasing industry hotshots, says Harvey. Candidates are being held under the microscope more than ever. The company looks at potential hires from three different levels, he says:

- Organizational —

- is the candidate a good fit for the organization’s values and behaviors?

- Management and leadership —

- does he or she have leadership skills and the capability to positively impact others?

- Job —

- does the candidate have the right skills for the available position?

“There’s so much more to look for now,” Harvey says. “If you’re a matrix company like AstraZeneca, you want to make sure somebody can succeed here. If there’s not an organizational fit, you already know that person’s not going to stay.”

Companies are maturing in how they use the Internet for recruiting purposes, Kneece adds. They’re being more cautious about which ads they post and what they say in them. And they’re tracking data on which portals have led them most often to hiring successes. The message for pharma job seekers: The days of posting your resume on Monster.com and snagging a plum job are gone.

Companies are also doing more number crunching in regards to staffing forecasts as well. “More analytics are being used to get better at predicting workload needs six to 12 months down the road,” says Jock of Kelly Scientific. After 12 months, “the situation gets cloudier,” he says. “You don’t know if the right person is going to be available. There’s a very short shelf life for the right skills.”

The right stuff, or the right fit?

Which skills have the shortest shelf life these days? Biotech experts with experience in proteomics, genomics and individualized medicine, Jock says, and engineers with strong skills in informatics and analytics. Workers with these skills who also have the soft skills, such as those for communication and teamwork, are snatched up quickly, he says, with a 30-day shelf life, and even half of that on the East and West coasts, he says.

The boom in building new plants and retrofitting existing ones is fueling growth in jobs for project engineers, and workers with experience in start-up and commissioning, and validation and regulation, says Brannagan of KForce. The Northeast, California and Mid-Atlantic pharmaceutical hotbeds such as Rockville, Md. are the places to be, she says. And people who have regulatory expertise are in greater demand than ever, she says. An FDA background or experience in regulatory or compliance issues will always serve candidates well, agrees Kneece.

Needs for particular skill sets ebb and flow, says AstraZeneca’s Harvey. Harder to find are candidates with leadership qualities, particularly innovative thinking, which is forcing AstraZeneca to look outside pharmaceuticals. “We in pharmaceuticals have stolen from each other for 20 years or more, and we’ve never been the most innovative industry,” he says. “To be a top company, you’ve got to be more innovative, but you’re not going to get that by taking people from Wyeth and bringing them to AstraZeneca. You need people who have innovated in other fields.” A number of operational excellence specialists, IT and industrial engineers are being employed from automotive and other industries.

The great divide

One of the major undercurrents of this year’s survey is of disconnect and disappointment with the industry — among women, minorities, white men and younger workers, as well as industry veterans.

Some of this can be attributed to the industry’s flagging image. A sampling of your comments:

- “The industry is the worst that I have seen it in the 20 years I have worked in it. This impacts everything from morale to the company’s ability to raise capital.”

- "The negative public image is correct. Leadership and vision are lacking. FDA and the industry are too stagnant and self-serving, and CEOs and management are paid too much.”

- “I am concerned about the push to medicate people somewhat flippantly. The TV commercialization of drugs is appalling.”

Public perception presents a clear threat to the industry’s ability to lure good workers. “I would be dishonest if I didn’t say that it has some impact on attraction and retention,” says Harvey. “It’s not a huge factor yet, but as an industry, we’ve got a year or two to figure out what we stand for besides high profit margins.”

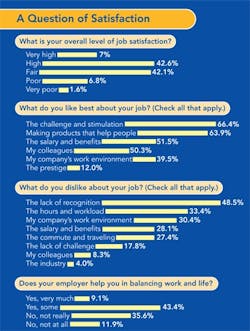

Many of you feel that your employers don’t care about you, or expect too much. Nearly 50% of you felt that your employer does not help in balancing work and life (see "A Question of Satisfaction" graphic, below). “My company says that it supports work-life balance,” one survey-taker wrote, “but when push comes to shove, my managers have placed business needs first.”

Singing the automation blues

The industry trend toward increased automation has, of course, taken its toll on the number of jobs available. It has also left many pharma workers feeling lost within the machine. “Activities that used to take place person to person are now all done by computer input,” said one respondent. “The personal touch is being lost.”

“Management is obsessed with measuring every aspect of the business process in order to trim a few dollars,” said an employee at a major biotech firm. “The burden of all the measurement falls on the workers, who must indulge management in their ‘metrics’ while still performing an ever-growing number of routine duties.”

The demand for absolute efficiency and speed in bringing products to market is also exacting a toll. “As a new lean, mean business unit, we are expected to accomplish the same results in one-third of the time without additional resources, compensation, or recognition,” one pharma worker said. “When every day, every lot is an emergency, it just isn’t fun anymore.”

Mars and Venus

Women comprised more than a quarter of our survey respondents. More than 55% of them said that their overall level of job satisfaction was high or very high, compared with just 50% of men.

While it appears that women are gaining upward mobility and landing management positions, salaries may not yet be equitable. Men and women express widely divergent views on the topic. When asked whether men earn more money than women, given equal skills and experience, 34.5% of men answered yes, compared to over 65% of women (see sidebar, "A Level Playing Field?" below).

| For a graphic detailing the demographics of our survey respondents, go to the end of this article. |

Some 75% of men claimed that the state of gender equality within their facility is either good or great; in comparison, just over 50% of women expressed this view. “I don’t think I’ve been treated any differently than men in my 15 years in the industry,” says one female validation manager. However, she admits she has witnessed discrimination and that there are subtle challenges to being a woman in the industry. “There’s a large group of men who like to go out to play golf and have drinks together,” she says. “It’s not really work-related, but it does factor into relationships and how things work at the plant.”

Women in pharmaceuticals are in a bit of a Catch-22, says one professional recruiter, speaking anonymously. The more capable they are, the fiercer the competition for their services, and the more concerned potential employers are that they won’t be able to retain them for the long haul. Even in this day and age, many companies still see a risk in hiring women of child-bearing age, he admits. “They wonder, is she really going to be with us in five years?”

The African American experience

Even though many respondents described the workplace as color blind and the playing field as level, our survey reveals a different story — depending on whom you ask. When asked whether racial or ethnic discrimination were a problem within their facility, nearly 92% of white respondents said no. While only 10 respondents to our survey were black, their message is absolutely clear: eight of the 10 said that discrimination is a problem.

Those same eight also felt that, skills and experience being equal, white employees earn more than black employees. How did white employees respond? An overwhelming 88.8% believed that there was no salary discrimination based upon race.

“Don’t forget that there’s a glass ceiling for black men, too,” said one anonymous African American respondent, noting that this applied to his company, and to the industry as a whole.

The reverse discrimination argument

White, male employees who responded to our survey lashed out against any suggestion of racial or gender discrimination in the plant. A small sampling of these opinions:

- “A white Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) is no longer a valuable employee.”

- “Five of our last five manager promotions have been women. Is this another form of discrimination?”

- “Amgen is overly diversified. They practice reverse discrimination in their sponsorship of clubs such as AWIN (Amgen Women’s Interactive Network) and a gay and lesbian club.”

Manufacturers walk a tightrope, striving for meaningful diversity while remaining impartial to qualified candidates. “As long as a component of diversity is compliance with a regulatory law, there will be concerns about it being compulsory,” says Deborah Dagit, Merck’s executive director of diversity and work life. “Diversity is by nature controversial, and we’d be fooling ourselves to think otherwise.”

Merck regularly ranks high on the list of best companies to work for, particularly for women and minorities. One of the secrets of that success, Dagit says, is taking a broad view of diversity — one that considers age, religion, geography, even styles of thought and behavior — and seeing it as a competitive advantage.

Perhaps what is most encouraging, she says, is that young professionals — whether male or female, white or minority — are demanding diversity of potential employers. “It’s difficult to attract Generation X or Y, regardless of salary, if you don’t have diversity among your employees,” she says. “You can damage your brand without it.”

For career-minded professionals, Dagit advises, “Understand the marketplace, and prove to employers that you are sensitive towards people who differ from you, and can work successfully with them.”

|

A LEVEL PLAYING FIELD?

Experience and skills being equal, do you feel that men in your facility earn more money than women?

Experience and skills being equal, do you feel that white employees earn more money and have more opportunity than employees from other backgrounds?

Is racial or ethnic discrimination a problem within your facility? |

|

ADVICE FOR THE YOUNG (AND NOT SO YOUNG) Gone are the days of introverted specialists who spend their entire careers within the safety and comfort of their immediate peers. If you’re serious about career development, you’ve got to become a jack of many trades, and be able to tell the world what you know and think. Chris Jock, VP and GM of global operations for Kelly Scientific Resources (Troy, Mich.), shares critical advice for career building:

|