Since the term “Lean” was first coined in 1990(to describe the manufacturing approach being used in Toyota factories in Japan), the space has become littered with lean programs in their various guises, such as Lean Manufacturing, Six Sigma, and Lean Sigma. These programs are usually high on education, but often lack sufficient emphasis on the necessary paradigm change to make a real, sustained impact on a company’s work practices.

Furthermore, while the literature assures us that Lean Manufacturing principles can be applied to any business process, many lean programs outside of Manufacturing still struggle to make these principles relevant. In the Life Sciences, this failure means that a significant opportunity for cost savings in the business—in particular, Quality Control and Quality Assurance processes—is overlooked.

At the core of this missed opportunity is a subtle misunderstanding of the real intent of Lean. By its original definition, Lean is about “the complete and thorough elimination of wasteful practices.” Unfortunately many companies read this intent as simply “elimination of waste.” This intuitively leads them down the trail of setting up projects which address only one of the three wasteful practices—the one called muda in the original Japanese texts.

There are various types of muda described in the Lean literature: Overproduction, Delays (Waiting), Transporting, Moving, Over-Processing (Rework), Inventory, Making Defective Parts. Chasing down muda is intuitively straightforward. Everyone on a project team can contribute to drawing a Value Stream Map. Indeed, this is a good tool to help everyone to see the Value-Add activities in their process and separate them from the Non-Value-Add (NVA) muda. It is also, then, relatively intuitive to go about addressing the wasteful NVA activities, so that wastes such as excessive movement (of product, samples, batch records, etc.), or causes of rework, invalid tests, and corrections can be reduced or eliminated.

Beyond Muda

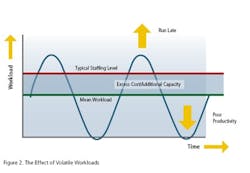

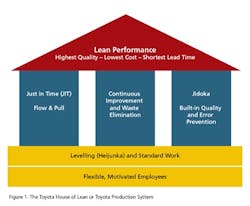

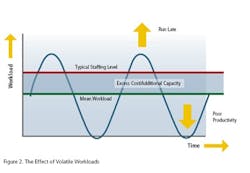

However, there are two other wasteful practices to consider: mura (unevenness, i.e. workload volatility) and muri (over-burden, i.e. peaks in workload caused by volatility). Addressing these necessitates the implementation of levelled workloads to enable the creation of product flow. And if we look at the Toyota “House of Lean” (Figure 1), where do we find this aspect of Lean activity? Right at the foundation of the house!So, we cannot expect waste elimination activities alone to build our House of Lean. Yes, they do contribute to a significant pillar, but this pillar is built on sand unless we address the other wasteful practices which are rooted in volatility. This was always the original intent of Lean. But we have found time and time again that this original intent got somehow lost in translation, whether in translation from Japanese to English or from Manufacturing to other business processes. Therefore, BSM Ireland ( uses the phrase Real Lean when we refer to a back-to-the-real-intent-of-Lean approach.

Companies need to be reminded (at best) and mostly simply made aware (and even then convinced through proven, cost-saving implementations) of the principles of Real Lean. But why is this the case? Despite the fact that addressing volatility is not only critical to a successful Lean implementation, but is clearly at the very foundation of the well documented Lean House!

The reason for this is twofold. The first reason we have already alluded to: Value Stream Mapping and pursuing the “Seven Muda Wastes” is very tangible and intuitive—it is easy to mentally connect why moving a product, sample, or piece of paper does not add value, and how moving it less can therefore save a person time. So when something makes immediate sense, we are likely to do it.On the other hand (and this is the second reason), it’s not as immediately obvious how simply levelling your workload and flow can save you anything. “You mean to tell me that I do the same amount of work on the product, sample or paper, just do it at a different time? How can that save me anything?”Pfizer: Paradise Regained

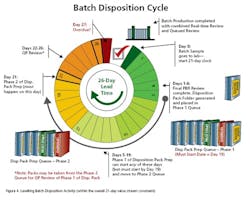

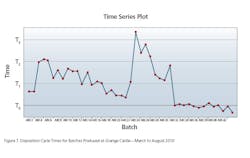

BSM Ireland has partnered with Pfizer on a corporate Lean Lab program, as well as a Lean Batch Disposition project at Pfizer’s Biotech site in Grange Castle, Ireland.

The Pfizer Lean story is an excellent demonstration of the benefits of Real Lean. More specifically it shows how, with some creativity and effort, Lean principles can be adapted to significantly improve business processes outside of Manufacturing—namely, QA and QC.

It’s worth noting that the goals of lean in QC/QA are the same as lean in Manufacturing or anywhere else—i.e. improving performance via the introduction of flow and the elimination of waste. But, labs and batch disposition processes are not the same as manufacturing, so we have to think about our Lean solutions differently.

- There is typically more volatility in both volume and mix.

- Labs have a complex mix of routine and non-routine testing/review activities—e.g., preparation of standards, folders, investigations, and so on.

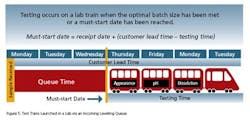

- Single-piece flow is generally uneconomical and unfeasible in the lab—e.g., test equipment is most efficiently run with more than one sample.

- There is generally less of an operational excellence/productivity focus—Manufacturing has dedicated production engineers, labs do not.

- The significant wastes are different and harder to reduce or eliminate.

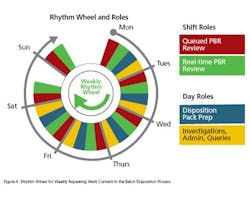

- They allow recovery of much of the volatility losses.

- Because they control the workload and the mix they allow the design of well balanced productive roles that make good use of people’s time—i.e., they “solve the problem once” and keep using the solution.

- They eliminate the need for elaborate short term planning and scheduling processes.

- They facilitate fixed repeating sequences of operation and “economies of repetition.”