Russ Somma: Building Better Partnerships by Leveraging QbD

Editor’s note: In our recent webcast, “Operational Excellence for Building Better Partnerships”, Russ Somma outlined the application of QbD principles to outsourcing partnerships. The following is a transcription of the main elements of that talk:

We need to be clear about scope. The present climate looks upon Quality by Design as an approach or option for the filing of NDAs. But option is the operative word here. The aspects of QbD can be looked at as a business practices manual, and many fail to leverage the opportunity to use aspects of QbD to focus business and development plans.

Within those plans are contract agreements with various product and service providers. QbD does not become the driving factor of partnerships, but it becomes the philosophy against which one sets up strong partnerships.

Just as Quality by Design is best defined in ICH guidances Q8 through Q10, so, too, can partnerships (Figure 1):

ICH Q8 (Pharmaceutical Development): Collecting the knowledge needed to cast a partnership.

ICH Q9 (Quality Risk Management): Application to our sourcing needs using the knowledge.

Q10 (Quality Systems—i.e. “The Enablers”): The maintenance of our product, process and the partnership through the lifecycle of the product, and the fostering of understanding between the two organizations in an outsourcing situation.

Figure 1. How QbD Supports Partnerships

The Sourcing-QbD Connection

Manufacturers have always questioned whether there is significant payback in Quality by Design. They might say, “I don’t see the flexibility, I see a lot of data being shared, no clear pathway is provided for filing, and it’s expensive.” Those are all true statements, but what we’re talking about here are the precepts of Quality by Design—the way you think about putting things together and how you leverage them when you go to procurement, when you go to setting up partnerships. Let’s not focus on the regulatory aspects, but on what Quality by Design tells us to do.

In establishing and maintaining partnerships, were we working under the delusion of Quality by Accident before? Of course not, but QbD affords us the opportunity to rethink and enable our sourcing initiatives.

We make our own opportunities, and Quality by Design is very clear. The items in Table 1 can be looked at as an inventory of information. If we forget the buzzwords like Quality Analysis and Design Space and look at drug substance aspects or product requirements, we start to see that we have a blueprint to understand better what our product expectations are and how we move forward.

Table 1. Building an Inventory: Define Our Quality Analysis and Design Space

- Drug substance specifications which include physicochemical properties

- Drug product specifications as well as basic knowledge of excipient interactions and process understanding

- Raw material characteristics and variability

- The envisioned sourcing partner and their related facility design, and capacity through the product lifecycle

- Target product profile, “desired state”

- Stability of clinical forms / prototype as well as drug substance

The target product profile should be emphasized—it is absolutely imperative but some companies fail to do it. Yet it provides documented proof of what we expect the product to be, and what we expect the capacity to be. And this is looking forward. It is the lifecycle. This is the flag under which everybody marches, internally and subsequently externally to the outsourcing partner.

Leveraging QbD, Crafting a Strategy

Components which are needed to address a conventional regulatory review are fundamentally those needed to craft a sourcing strategy. We call it Quality by Design, we may just as well call it good development. Whatever it is, these things all have to be leveraged in putting together a sourcing strategy:

- An understanding of the product and process in terms of fundamental, mechanistic properties as opposed to empirical.

- Utilization of prior knowledge in defining product, process and facility—either your own or that of your partner.

- Partnerships to accommodate the product’s lifecycle.

Lifecycle is the key word. That’s the business driver. If we apply this to partnerships we have, we’re going to reduce costs and shorten time to market. We’re not going to have the inevitable accidents. Quality by Design enables the inventory of information and how to think about the data objectively.

Many industries, from biotech to medical devices, have used the precepts of QbD effectively in a range of situations. They all share a similar vision speed to market, cost reduction and flexibility:

- A small biotech firm conducts a knowledge inventory / design space as they approach submission of a novel delivery system for a vaccine.

- A start-up molecular design/discovery firm looking to develop an early stage CMC package with the required “curb appeal” for potential partners.

- A large-scale device manufacturer looking toward seamless process introduction and cost reduction as they enter the combination product market place.

These are examples of companies that have put these ideas into practice. It is not Quality by Design to make a filing. It is Quality by Design to enable a business plan, and from that business plan to foster outsourcing or whatever partnerships are necessary.

Desired State

How do we get there? It begins with knowledge, in its many forms. Knowledge may be categorized into several areas which we need to manage during development.

- Incremental knowledge is a result of ongoing activities and grows with each development project.

- Tacit knowledge or “sticky knowledge” can not be communicated to a partner in a formal, systematic or codified language. It is commonly referred to as a feel for the process.

- Explicit knowledge may be set down in procedures and easily codified.

The one that often creates a problem is tacit knowledge. It cannot be communicated. It’s something that people know but cannot be documented or codified or given to a partner. Often, this is where things unravel.

Explicit knowledge is what sourcing is all about. It is cost effective and transferable. It produces a well-defined set of core technologies. It speeds development and process introduction. And we deal with explicit knowledge daily. It is the basis of our work (for example, robust formulations, meaningful specifications, facility design).

By growing our explicit organizational knowledge, we begin to develop a resource by which we can strengthen relationships with partners and establish a course towards a sort of Desired State for outsourcing.

How do we get to the Desired State, which is outlined in the target product profile? Increase our mutual organizational knowledge. Ask ourselves some broad-based questions and begin to put together inventory and constructs around them.

- What is needed in a submission?

- What will the partner provide in terms of flexibility?

- What is needed to release a product?

- What is needed to manufacture a product?

- What will be our capacity needs over the product lifecycle?

- What is needed to control a product?

- What would be needed to manage post-approval submissions?

Three Steps Forward

Taking a simplistic approach, I always suggest going with a three-step process—the sub-bullets here are things that you can create yourself.

Step 1: What knowledge do we have to shape these areas?

- Scientific elements to be considered and explored for potential product attributes and process parameters.

- Prior knowledge across multi-disciplines and therapeutic areas that may impact product attributes or process parameters.

- We can begin to define our knowledge area and understand what is critical to our product.

Step 2: Refine the knowledge so we can make a product.

- We apply risk assessment and experimental design to form a space within which we know we can make a product.

Step 3: Control the product and process to deliver consistent results.

- Application of process understanding, engineering, equipment, process controls and our sourcing requirements.

If you look at these three steps, we start to get three shopping baskets full and we start to understand what we need to do when we look for assistance externally.

Assessing Criticality and Risk

My frequent admonition to clients is not to get into a debate about what is critical. A lot of time can be wasted in this debate. This is often one of the hurdles that people see, but criticality is a function of risk. We have to look at it against a backdrop of what risk is necessary, and that risk is often dependent upon patient safety. But it is also dependent upon manufacturability—what is the risk of batches not meeting requirements, of not maintaining a lifecycle or maintaining a market presence?

One aspect which must be made clear to all the players is the need defined by ICH-Q9 (Risk Management) concerning risk. A sponsor must work toward a system which is based on Risk Knowledge or “What If” aspects. This has two components: Risk Assessment and Risk Control. The path to achieve this goal must be to leverage product and process knowledge.

This task, knowledge management, must be seen as an enabler of all the functions and may best be dealt with in a well-defined and agreed to “Mutual Quality System” between the sponsor and the partner. In my experience, even when you go to an outsourcing partner and they’re manufacturing your product, there can be a disconnect between what we feel is acceptable or unacceptable and what the partner feels is or is not acceptable. These things have to be agreed upon because those sorts of things create delays just as much as a bad formulation or faulty process.

Risk should be assessed based on cause and effect and relative to the following criteria:

- Probability – the likelihood of a consequence

- Severity – the magnitude of the impact of a consequence

- Detectability – the level or ability at which a consequence can be measured

- Sensitivity – the attenuation of interactions between multivariate dimensions

This is how we whittle down criticality and get a concrete and pragmatic sense of the things that need to get done. These are things that have to get looked at, and our partner has to look at as well.

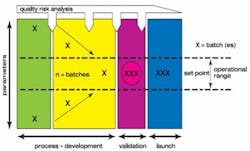

If a partner does not, we have to provide them with a package so that it gets done for them. One of the things we do is a risk analysis (Figure 2). This is a living document, and this becomes very important when you provide this to a partner as a living document.

Figure 2. Illustration of a Product Risk Analysis

First, we consider these answers internally. We ask ourselves: when we begin to define sourcing needs and required capacity, do we have all these aspects covered? Are risk and criticality fully understood within a context of knowledge management and sharing between partners?

Consider these questions we should be asking internally. If answered upfront they have a significant effect on the sourcing strategy and position us for success—so that we and partners can be a unified team:

- What properties of the drug substance effect product performance?

- What is the formulation intended to do?

- What are the special requirements of the drug substance and drug product?

- How do we define the critical process steps?

- What are the process parameters for each step and how are they monitored and controlled?

- What must we design into the facility in order to assure we meet critical quality attributes of the product?

These things have to be communicated. The manner in which we answer these questions and allocate risk greatly affects our business plan and the cost of the process and/or the product supplied by our partner.

Summary

The development aspects needed to do QbD are those needed to form a sound relationship. They are complicated and challenging to be implemented, using our internal resources as well as our external partnerships’ expertise. They are complicated not in terms of doing experiments and technical work but in terms of inventorying and putting together a library of knowledge.

Systematic data provides key leverage for CMC. Answering questions upfront prevents the fishing expedition and determining who did what to who. It gives you a clear path in the lifecycle. You know where you’re going to go so procurement can make the adequate partnerships. . .

We have the majority of the data available but need to configure it to defend our product, supply chain and process. The systems to achieve this have been effectively applied to existing business models. With product knowledge we are positioned for success and to deal with QbD NDAs and sourcing requirements.

Most importantly, you’ve got to know what you do not know. The only way you find that out is by talking to everyone—procurement, manufacturing, development, clinical, therapeutic areas, marketing, distribution. Everybody has to be included. As they say in the Navy, it only takes one guy to sink the ship. In our case, it only takes one missing piece of information.

About Russ Somma

Russ Somma, Ph.D., is President of SommaTech, LLC. Dr. Somma has more than 30 years of pharmaceutical industry experience, specifically in the areas of production troubleshooting, dosage form development, manufacturing scale-up, technology transfer and project management. He has a particular technical interest in the area of solid dosage forms and is considered a subject matter expert in technology transfer and Quality by Design. He is a “Hammer Award” winner, presented by Vice President Al Gore’s Committee for National Performance Review and, most recently was awarded ISPE’s prestigious Max Seales Yonker Member of the Year Award (2007) for his lifetime contributions to the pharmaceutical industry.