Faced with empty pipelines, expiring patents, pricing pressures, generic competition, and growing government and consumer challenges, pharmaceutical companies are increasingly transforming their product value chains in order to increase overall profitability. Many big pharma companies are deconstructing their vertically integrated value chains. Some, for example, are selling manufacturing facilities or divesting mature products that are not part of their core business. Conversely, many small companies are creating supply chains that can accommodate expected growth, as demand for their products outstrips fledging value chains.

But whether they are growing or disaggregating their value chains, companies face a growing number of increasingly difficult and complex decisions: whether to insource or outsource or to license. They must also build in capacity flexibility, to adapt quickly to changing business conditions. In this demanding environment, the usual supply chain objectives of efficiency and effectiveness alone no longer suffice. The new mantra is efficiency, effectiveness, and excellence – what we call “value chain E3.” Simply stated:

- Efficiency

- is doing things right.

- Effectiveness

- is doing the right things.

- Excellence

- is doing “the right things right” and achieving the highest quality.

In the past decade, many organizations have diligently focused on efficiency, in some cases to a fault. Despite the complexity of the choices they face, they make one-off decisions, often simply trying to optimize as cost-effectively as possible one isolated activity in the value chain. But value chain interdependencies preclude separate, sequential focus on each issue or option. While optimizing one element may improve that particular activity, it can also have a negative impact on another interdependent element somewhere else along the value chain.

Focus can no longer be separate and sequential. Instead it must be systematic and simultaneous, examining all strategic issues and options in order to optimize the overall E3 of the value chain and to maximize its financial value. This article will outline a proven approach for building “options thinking” into value chain decision-making and a method for accurately evaluating supply chain decisions, while explicitly accounting for the unique risks and uncertainties that make those decisions difficult. Although these techniques have been used at the “macro” level, for corporate decisionmaking, they can also be applied at the “micro” level, of the individual division, facility or line level.

Understanding “Options Thinking”

Building E3 into product value chain decisions requires a standardized decision-making process. There are a number of organizational structures that can be adopted, such as a steering committee composed of the decision-makers and a separate working team of individuals who provide the insights and analyses to support the steering committee discussions. But regardless of the structure employed, the goal of the decision-makers should be to identify the most valuable actions among all the many value chain choices by examining multiple competing alternatives and options. Decision-makers should be able to consistently, repeatedly, and reliably help the company strike the right balance across investments in product supply, capacity flexibility, total cost, and timing of profitability in the face of risk and uncertainty.

In this more holistic approach, the operative principle is to optimize the flow of the entire value chain and make decisions about its various interdependent parts in relation to each other. Therefore each alternative to be considered will comprise an entire mosaic of interdependent elements. Moreover, the alternative must be genuine. In other words, it must be:

- Attractive:

- It should generate reasonable financial return or other business advantages.

- Doable:

- It should be achievable, given existing resources.

- Different:

- It must differ in some significant way from others. It can, for example, require a more aggressive approach, a different strategy or investment level.

Measuring Value

In addition to generating multiple genuine alternatives, a consistent method and appropriate metric must be used to evaluate and compare those alternatives. A number of value-chain metrics are typically used, including inventory turns, service level performance, and forecasting errors.

However, one financial measure, net present value (NPV) of free cash flow is the best choice. NPV is a good surrogate measure for shareholder value creation; it can be applied across all of the various product value chain decisions; and rigorously and explicitly addresses risk and uncertainty. Understanding the impact of value chain decisions through the NPV of free cash flow creates a level playing field of comparison for all decisions, and enables the integration of the impact of these decisions to provide a clear understanding of why one comprehensive strategy is better than another.

It should be noted, however, that even with a variety of genuine alternatives and a consistent basis of comparison like NPV, the approach does not produce the “right” answer. Rather, it provides you with the basis for reaching a good decision. Armed with attractive alternatives and the knowledge of what each alternative is worth, you can make your decision based on such factors as your appetite for investment, tolerance for risk, on total value, on return on investment, and the like. The right answer is the answer that is right for you.

Options Thinking in Action

To understand how options thinking works in detail, consider the case of one pharmaceutical manufacturer. The company was grappling with the strategic decision of either becoming a “vertically integrated” or a “virtual” business.

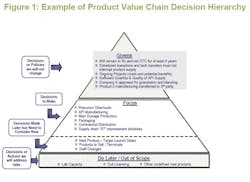

Senior executives had substantially different opinions on how to structure the overall value chain to support their projected rapid growth. To focus the problem clearly, a steering committee employed a Decision Hierarchy (Figure 1, below) and a Strategic Options Table (Figure 2, below). The Decision Hierarchy is a simple tool used to state, clearly, the scope of the decision process by distinguishing among:

- Decisions or policies that have been made and will be assumed to be “givens”;

- Decisions that will be the focus of the process and will be analyzed and decided at its conclusion;

- Decisions that need to be accounted for in the process but that will be made outside the scope of the process; and

- Downstream decisions or actions that are outside the scope of the current process and do not yet need to be addressed.

The givens included the company’s intention to stay in the prescription drug business, to ensure that changes did not disrupt current drug supply or ongoing projects, to maintain sufficient API supply, to use an outside source for granulation and blending, and to transfer the manufacturing of one of its products to a third party. Having established those givens, the committee was then able to determine six key issues in the value chain on which to focus: precursor chemicals, API manufacturing, main dosage production, packaging, commercial distribution, and E3 improvement initiatives.

Creating Comprehensive Strategic Options

After agreeing on key issues, the steering committee created the strategic options they believed were feasible and warranted financial evaluation. Committee members also defined the existing plan – “current course & speed” (CCS) — in order to be able to compare the two, and to see what value would be created if they stuck to the existing plan.

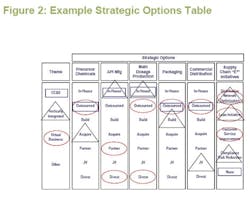

In constructing the Strategic Options Table depicted in Figure 2, the committee first considered the column labeled “Precursor Chemicals.” They then worked down the list of choices in the column and identified the best choice for each of the overall strategic “themes” under consideration: CCS, vertical integration, and virtual business. (“Other” refers to unspecified strategic themes into which the unchosen options in each column might presumably fall.)

In working down the column, the committee assigned each of the strategic themes to the appropriate choice, marking the choice, in this case, with a rectangle to indicate current practice, a triangle to indicate the practice to be followed in vertical integration, and an oval to indicate a virtual business practice. (It should be noted that for purposes of illustration this table has been kept relatively simple and uniform. Typically, the identical list of choices will not be found under each of the key issues, as here.)

Once the committee had worked down all six of the key decision columns, it had a picture of what each broad strategic option for the value chain looked like. For example, vertical integration would mean: acquiring the capability to produce precursor chemicals, manufacturing APIs in-house, keeping main dosage production in-house, building a packaging capability, forming a joint venture for distribution, and undertaking “supply chain E3” initiatives in distribution network optimization, “Lean,” and compliance risk reduction. The virtual option would mean: outsourcing precursor chemicals, divesting the existing API and main dosage production capabilities and securing partners to provide them, outsourcing packaging and commercial distribution, and undertaking “E3” initiatives in distribution network optimization, “Lean,” and customer service. The exercise also gave the committee a clear picture of the current CC&S plan.

Valuing Competing Options

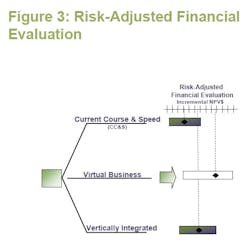

To evaluate these different strategic options, a financial model was created that included all of the key risks and uncertainties that the steering committee and other subject matter experts believed were important factors in making value chain decisions. Key risks and uncertainties included such factors as management bandwidth, compliance risk, outsourcing costs, emerging technologies, and time-to-launch. Each of these issues was addressed in the financial risk-adjusted evaluation of each strategy (Figure 3, below).

As the risk-adjusted evaluation shows, the virtual business option would create more financial value than the vertical option and far more value than maintaining current course and speed. This did not mean the company should necessarily choose this option, but gave its steering committee a sound basis for comparing different choices and choosing them based on value, investment, risk and other factors.

A Track Record of Results

A systematic approach to improving the value chain provides a consistent, repeatable and reliable basis for making decisions in the face of complexity, risk, and uncertainty. This approach, developed and honed over the last 20 years, has an impressive track record:

- In some 70 percent of cases, decision-makers committed to a different alternative and path of action than their existing plan.

- In almost every case, the approach identified alternatives that promised 30 – 100 percent improvement over the current plan as measured in expected net present value (NPV) of free cash flow.

- In 95 percent of cases, the recommendations were fully funded and backed by real organizational commitment, based in part on the fact that the methods that were used were systematic, and inspired confidence.

By using this alternative-based approach to value chain decisions, manufacturing and operations executives, and even leaders at the local level — facility managers or line leaders — can genuinely explore significantly different options, breaking them free of the incremental decision-making that keeps organizations from realizing the full benefits of their value chains.

About the Authors

All three authors are with Tunnell Consulting. Brian W. Hagen, Ph.D., is Managing Director, Raymond L. Manganelli, Ph.D., is Senior Managing Director, and Thomas L. McGurk is Practice Director.