One of the biggest problems with government oversight is the sheer size of the government; often a single agency speaks with several voices. The blogs and chat sites (like LinkedIn) are full of statements like, “One inspector told me my (QbD) plan was OK, but another wanted it more like cGMPs.” In fact, no one at FDA is willing to comment (officially) on QbD now; it is rumored that they are attempting to come up with “something better.”

When a large company I worked for received a 483 (back in the early ’80s), one item was that the QC department reported to the director of production, a clear conflict of interest. So, the FDA believes that you can’t enforce rules when the entity you are trying to correct is above you in the food chain? Let’s follow that reasoning and apply it to Congress and its current relationship with the FDA.

Congress, motivated for many reasons but largely economic, has committed to the ideal of a large, ongoing generic drug presence in the market. They also oversee the FDA budget and can directly affect their lab space, equipment and personnel levels. Does anyone see a problem here?

Clearly, cGMPs ask for “meaningful in-process tests.” The other “inconvenient” truth is that GMPs call for “statistically significant” numbers of final dosage forms to be tested. While the current paradigm of six tablets or capsules for dissolution and 20 tablets/capsules for assay may have been fine in the 1950s, when lots were only in the hundred-thousands; but, now, with lots routinely in the millions, these numbers seem insufficient.

Take a batch of 5 million tablets, for example; 20 units assayed would represent a 0.0004% sample. This leads to the question, “What do we do for continuous processing?” In that case, a drug maker may be producing many millions of doses over a week or so. How, then, do we sample this under GMPs? Of course, the answer is we can’t; we must sample under QbD/PAT protocols. In that case, we are actually monitoring several tens of thousands of doses. By analogy, shouldn’t we sample tens of thousands of doses under current GMP testing? Well, let’s see what that could entail. A typical lot of product might have to have 20-25,000 assays to be considered “statistically significant.”

That number would be a crushing burden, even for the largest proprietary manufacturers and would be the death of a large number of small to mid-size generic firms. So, we have a case where we have seemingly conflicting goals: The FDA is tasked with protecting the health of patients, while the Congress is committed to keeping economically attractive generics available. In theory, generics are identical to the initial products they imitate.

However, cases are mounting where clinical data is not generated and a given generic product receives a “biowaiver.” That is, all a generic company needs to do is show the same dissolution profile as the original product (and assumes that it will show a similar IVIVC — in vitro/in vivo correlation). This is usually done for immediate release doses.

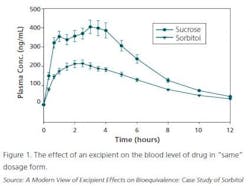

However, the excipients can make a difference not seen in a standard dissolution test, as seen in Figure 1.

So, I must ask: At what expense in safety does this economic and political expediency come? Are we being protected adequately or do the baser political interests of Congress create an untenable conflict because it is currently the “boss” of the FDA? Would we be better off without politics dictating drug policy? My bet is that we would — perhaps it is time for the FDA to become an entity independent of congressional oversight.

Published in the September 2013 edition of Pharmaceutical Manufacturing magazine