Measuring quality culture is essential to improving mindsets and behaviors in pharma companies. The challenges to measuring culture are significant, but our research demonstrates that they can be overcome. While there is no ultimate metric for culture, good measures are available, each with proven correlation to quality outcomes. Indeed, companies with a strong quality culture are distinguished by their ability to measure culture and apply those insights to culture improvement efforts.

More than ever, quality culture is top of mind for pharma industry stakeholders. Industry leaders recognize that quality culture is essential to ensuring good quality, following the examples of advanced industries, such as automotive and aerospace. Industry associations are conducting research on the effectiveness of tools for building and sustaining a quality culture. And regulators publicly stress the importance of instilling a culture that prioritizes continuous improvement of quality. For example, Janet Woodcock, director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at the FDA, has spoken at many industry events in recent years about the agency’s intent to use the regulatory process to foster a quality culture from the shop floor to the executive suite.

But even as the industry embarks on this journey toward a better quality culture, some stakeholders do not yet regard the assessment and measurement of culture as the key foundational step. Many are convinced that quality culture cannot or should not be measured. We strongly disagree. In fact, we believe that quality culture is not only measurable, but also the most important indicator of a pharma company’s quality performance, strongly correlated with impact. As a result, we see measuring, and paying attention to what the measures indicate, as important cultural signals.

We developed our perspective during the past decade in the course of our work with many companies in pharma and our partnership on quality metrics with ISPE. Our research has demonstrated the feasibility and value of assessing and measuring pharma’s quality culture.

MEASURING QUALITY CULTURE IS CONTROVERSIAL, BUT NECESSARY

These concerns are valid and must be considered when designing or choosing the right measures. But the need to manage potential pitfalls should not deter companies from measuring quality culture. In the absence of baseline measurements, cultural improvement initiatives can target the wrong levers.

That’s why cultural change efforts should begin with quantifying both the baseline status and the future-state aspiration. By identifying the gap between the baseline and aspiration, the company can design initiatives to foster the required mind-set and behavioral changes. Once these initiatives are implemented, measurement would again help assess the impact and the progress toward the aspiration. Importantly, the measurement of culture must be done with the understanding that the goal is to promote improvement, not to reward static performance.

Measurements are essential for successful transformations in any context. Transformation success is not a given: two-thirds of transformations fail to achieve their objectives, as McKinsey research shows. CEOs and other executives indicate that metrics are a key factor contributing to the success of those relatively few transformations that do achieve their goals. The same research finds that approximately 70% of successful transformations have clear, unambiguous metrics for tracking progress and impact, compared with only 15% of unsuccessful transformations.

DEFINING AND ASSESSING QUALITY CULTURE

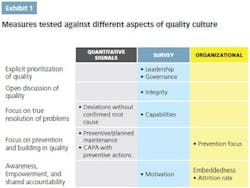

We believe a quality culture can best be observed in behaviors. Therefore, we used our experience with cultural transformations and input from pharma quality leaders to define a quality culture as one manifesting the following behaviors:

• Explicit prioritization of quality throughout the organization, including top-down communication and role modeling

• Open and transparent discussion of quality issues throughout the organization, including bottom-up communication and engagement

• Emphasis on truly resolving problems, finding the right root causes and addressing them to avoid future issues

• Focus on prevention and building in quality, rather than on firefighting

• Awareness of quality’s importance, empowerment to make quality decisions and take ownership of quality, and shared accountability.

The quality mindsets and behaviors also must be consistent with the company’s operating strategy and management infrastructure — only a congruous combination makes good quality possible and sustainable.

Quantitative metrics can serve as specific and comparable signals, even if each of them measures only a single aspect of a quality culture. They are also relatively easy to track once set up in the internal data systems. An aspiration defined through such metrics is clearly understandable and translatable into targets. To define the aspiration, the company needs to understand the optimal level of each measure and, ideally, compare it against benchmarks.

Quantitative metrics often provide signals for more than one aspect of quality. For example, preventive maintenance is both a best practice of the operating and technical system and a signal of the culture’s prevention focus.

Yet a quantitative metric may not have a linear relationship with quality culture, because the signals are typically influenced by multiple factors beyond culture. For example, human error rates depend not only on culture and mindset, but also on procedural complexity, process automation and training design.

Culture surveys are often successfully used to measure mindsets and behaviors across the organization. They are easy to administer and can be used at any organizational level. Ideally, they should be applied at the shop-floor level, to assess the mind-set of the people “touching the product.” A good survey should be able to discern behavioral differences between senior management and the shop-floor workers, as well as between quality and manufacturing functions.

Subjectivity of responses is a concern when conducting surveys. To address this, the survey must reach a sufficient number of people, especially on the front line where the products are created. And any survey must overcome design challenges, such as framing questions and choices with minimal, if any, room for misunderstanding, as well as maintaining consistency across different languages.

Organizational enablers measure whether the organization is set up to encourage a strong quality culture. These include how quality tasks are resourced and supported, basic organizational metrics such as attrition rates and tenures, and communication and connectivity enablers.

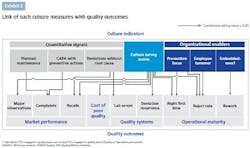

How well do metrics correlate with quality outcomes? Recent research has presented solid evidence that some of these metrics are correlated with quality outcomes. While correlation does not imply causation, and these outcomes are influenced by multiple factors, the correlation means that culture indicators can serve as useful signals for the health of a quality culture.

Quantitative signals. Two of the three quantitative metrics tested were preventive maintenance and CAPA with preventive actions, both signals for prevention focus. These metrics showed a positive correlation with the level of complaints: for example, planned maintenance rate explains approximately 45% of the variability in total complaints per million packs. The third quantitative signal was deviations without a confirmed root cause, a signal for the depth of problem-solving capabilities in the organization. It correlated with the level of recalls and is associated with better lab performance.

Culture surveys. Over the past several years, we have used the POBOS Quality Culture Survey with nearly 40,000 people across approximately 110 sites and 35 companies. The survey is organized around five main dimensions: 1) capabilities (such as problem solving and training), 2) governance (especially around metrics and knowledge), 3) leadership (a critical dimension focused on management presence and dialogue on the shop floor), 4) mindsets (responsibility for and awareness of quality), and 5) integrity (motivation, ethics, and openness). The POBOS Quality Culture Survey scores (using top-box scoring) correlated with market performance, compliance, cost of poor quality, quality systems effectiveness and operational maturity.

Organizational enablers. We have tested a variety of enablers, including:

Prevention focus: measured as the share of quality work spent on prevention-type activities, such as quality systems, training, policies and standards development, risk management, supplier quality and validation. It is correlated with right-first-time and reject rates.

Embeddedness: measured as the amount of quality work performed by manufacturing or other non-quality personnel as a share of all quality work. It is positively correlated with a lower rework rate.

Employee turnover: an enabler that promotes the sustainability of a quality culture through higher retention rates. A high attrition rate is correlated with a higher reject rate.

REACHING THE IDEAL STATE FOR MEASUREMENT

We have worked with multiple pharma companies to design a set of effective metrics, including ones that enable better understanding of quality culture. For example, in some cases, companies have combined quantitative metrics to create a culture score or index used for ongoing tracking on dashboards. In other cases, companies have introduced such metrics specifically in connection with a cultural transformation. Examples of the metrics we have seen in use include:

• Data reliability issues identified

• Process changes driven by the shop floor

• Issues identified during Gemba walks

• Percentage of attendance and due-dates adherence

• Increase in specific root causes

• Trend of repeat deviations

• Quality achievements rewarded

• Ideas generated by operators

The challenge is that, more often than not in this learning process, companies choose these metrics without rigorously assessing a variety of issues, including their suitability for measuring quality culture, means of avoiding the pitfalls discussed earlier (such as unintended consequences), and whether definitions differ between sites and organizational units. Designing the right set of metrics, based on company-specific gaps and aspirations, takes significant effort.

Few companies regularly use a targeted quality culture survey. Most often, companies include several quality questions in employee engagement or pulse surveys to avoid the need for a separate poll. While it is easier to piggyback on another survey, in our experience the questions selected are usually not optimal. In other cases, companies conduct a one-time run of an industry culture survey as part of a broader initiative. Although this helps establish a baseline, it is not institutionalized or used to measure cultural changes. It is still rare to find cases, in pharma or any other industry, in which a company invests in developing or subscribing to an optimized quality culture survey that is run regularly (daily or weekly) and that captures trends.

To reach the ideal state, companies should do the following:

• Use simple, high-frequency measures to monitor the pulse of the organization on the shop-floor level

• Track select quantitative metrics (using a balanced index or scorecard) regularly to detect signals of cultural shifts

• Run a quality culture survey annually to assess cultural shifts and progress toward closing gaps

• Define measures to ensure that each organizational enabler functions as desired to support a quality culture

Culture is so multifaceted that it cannot be captured by a single metric, but only through a panel of different measures. In the end, organizations must recognize that measures are only one way of understanding culture. Other means include walking the shop floor, talking to people and listening to what they say, which should be a daily task for quality leaders. A company can use such methods regularly or as part of an in-depth review to better understand the results of a measurement-based assessment.

A quality culture is a relatively simple idea. As Henry Ford famously said, “Quality means doing the right thing when no one is looking.” Even so, looking — and measuring what is observed — provides the basis for ensuring successful change. Fortunately, a quality culture is more susceptible to measurement than many pharma executives may realize. Although there is no silver bullet, there is a variety of good choices for measuring culture. Most important, executives should remember that measurement is only a means to an end — to inspire positive changes, the results of measuring a quality culture must be applied.