Beyond the Reporting Lines: Secrets of Successful Quality Organizations

What is the best way to design a quality organization to maximize effectiveness and minimize risk? That question is top of mind for pharmacos’ senior management teams everywhere. The catalysts of concern are no mystery: complexity and lack of supply chain transparency have tripped up many companies, and more-intense scrutiny and greater expectations from regulators leave pharmacos with no choice but to devote greater attention to improving efficiency and minimizing risk within the quality function.

Which raises the question of how exactly pharmacos can be both efficient and low risk. The FDA guidelines simply point out that a quality group needs to maintain independence from the operations group whose outputs it is meant to assess. There is no current best standard for organization design. So, it is up to pharmacos themselves to determine how best to manage reporting lines and deal with the appropriate degree of centralization as well as to define roles and responsibilities for quality activities as they relate to other functions. Furthermore, the quality organization’s design must deliver the levels of agility, cost, and risk that meet all necessary external standards—and that can be readily accepted by the whole organization.

With those questions in mind, McKinsey recently benchmarked the quality organizations of pharmacos worldwide. The study covered 30 pharmacos, including 16 of the top 25 companies globally. The research examined organization structures at both site and central levels, as well as governance mechanisms and other supporting organization practices.

The key finding of the research is that reporting structures are not predictive of quality outcomes; we found strong and weak performers in each of the structural models that we examined. What truly sets apart the top-performing quality organizations is excellence in execution, not organization structure.

Companies need to carefully align elements including governance, capabilities, organization culture, and rule setting with the chosen organization model. Our benchmarking and research provided the following insights:

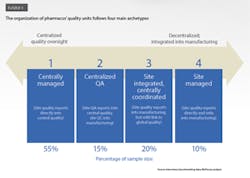

- There are two common design choices for all quality organizations: the degree of centralization and the degree of independence. From these, we have defined four archetypes.

- The most common design is a centralized/independent archetype—a model that is particularly favored by U.S. pharmacos and those that have recently faced compliance challenges.

- Comparisons of quality performance between the four archetypes show that organization design alone confers no real performance advantage.

- However, within each archetype there are unique pitfalls to be avoided—and lessons to be learned from top performers.

- No matter what the organization design, the ultimate objective is effective governance of all quality issues.

FOUR ORGANIZATION ARCHETYPES

When pharmaco executives discuss how pharmacos’ quality organizations should be designed, they often struggle to determine the degree to which there is central oversight and control over quality versus the degree to which quality is integrated into manufacturing.

In the past decade, more companies have chosen greater centralization. Survey respondents highlighted a need to address internal quality issues as well as external drivers—notably the U.S. FDA’s directional guidance on company-wide quality systems and adequate monitoring and risk management.

Our benchmarking research reveals that pharmacos use four main types of structure to design and manage their quality organizations (Exhibit 1). These range from more centralized and independent to more integrated and local. We look at each archetype in turn:

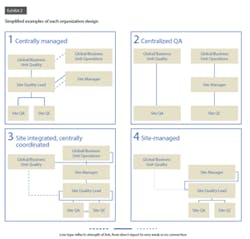

1. Centrally managed: site quality organizations report directly into central quality, with limited links to manufacturing

Approximately 55 percent of pharmacos use this archetype. In these companies, the central quality organization directly oversees processes, standards, and decision making for quality issues at the site level (Exhibit 2.) The link between the quality function and the operations function—whether at the site, regional, or business unit level—is quite varied in terms of its strength and nature. At some companies, the quality function does not even have dotted-line reporting to site management. Other companies have dotted lines from quality into operations from all levels, while still others have the central quality group reporting into the chief operating officer or head of operations.

Pharmacos that have adopted this organization model believe it gives the quality group an independent view of product quality, facilitates adoption of global company standards and sharing of best practices, and allows for rapid escalation and resolution of issues. At the site level, the quality organization gets an equal seat at the table with site management, which helps to give its managers more authority on operational matters.

2. Centralized QA: quality assurance is coordinated centrally, with quality control integrated into manufacturing

Fifteen percent of the pharmacos use this model. In this case, oversight for quality assurance (QA) is centralized, and quality control (QC) is handled by the manufacturing organization (Exhibit 2). Some of these organizations also have limited centralized QC functions (such as shared service labs or QC harmonization units) that report into the global quality function, along with site-level QA.

Pharmacos that integrate QC into manufacturing believe they will achieve greater efficiency and operational speed while reaping the advantages of global standards and central independent oversight. Some companies also think that QC teams can collaborate more effectively with production teams if they belong to the same unit given that QC work is essentially like production work: oriented toward output, efficiency, and service rather than involving policy creation or interpretation of regulations.

3. Site integrated, centrally coordinated: quality functions are integrated into manufacturing but with some centralized quality coordination

In these organizations—20 percent of our research sample—the quality function is embedded in the manufacturing organization, but a dotted-line reporting connection to central quality ensures consistent policies and procedures across sites (Exhibit 2). The quality function’s independence from operations is kept intact thanks to strict definitions of interfaces and allocation of roles and responsibilities between the two functions.

This model is perceived to promote better collaboration between quality and operations teams by including them within the same organization. The pharmacos that subscribe to this model see it as enabling greater operational efficiency and speed, faster decision making, and a sharper focus on customer service and business priorities; the model’s global guidance and monitoring of quality reduce compliance risk.

4. Site managed: quality activities are under plant management’s direct oversight

Some pharmacos (10 percent of the sample) integrate QA and QC into the site organization and have these units report to site management. The central quality organization, if it exists, typically has only basic reporting responsibilities and a weak functional link with the site quality group (Exhibit 2).

This model is advantageous if sites have a strong, autonomous quality culture and can implement local standards as needed. However, the largest movement in the past decade has seen companies transitioning away from this archetype in favor of increased central oversight.

STRUCTURE IS NOT A CATALYST FOR PERFORMANCE

Our benchmarking revealed empirical patterns:

- Company size does not heavily influence the choice of organization design.

- Company culture or history appears to have an influence on organization design. Companies that are more heterogeneous, or those formed through mergers, favor more decentralized archetypes, and those with a more homogeneous culture and common tools lean toward centralized structures.

- There are loose regional preferences:

- Pharmacos with U.S. headquarters tend to have both QA and QC in one organization, centrally managed.

- Pharmacos in Japan tend to integrate quality into manufacturing.

- Pharmacos in India tend to be more centralized.

- Pharmacos in Europe do not show a preference for any one type of organization design.

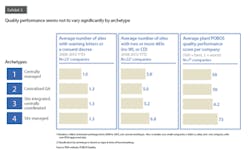

More interestingly, though, the choice of organization design has little or no bearing on superior quality or operational results (Exhibit 3). Companies in each archetype show very similar external quality performance (measured in terms of compliance).

Further, there is no meaningful difference across archetypes with respect to the level of site resources engaged in quality work. The average share of site employees engaged in quality activities varied from 28 percent to 32 percent among the four archetypes. There is also little difference in the size of the central quality organization among the three archetypes that demonstrate some degree of centralized reporting or coordination.

Comparing pharmacos’ structuring of quality functions with that of other industries, it’s plain to see that approaches are similar regardless of industry.

WHERE DOES ORGANIZATION DESIGN MAKE A DIFFERENCE?

Given that the choice of organization structure does not yield higher levels of quality and does not affect productivity, what does drive greater efficiency and effectiveness for the quality organization? We looked at the strengths and the challenges faced by companies at each end of the spectrum:

Strengths and challenges of more centralized models

Strongly centralized oversight, as featured in the “centrally managed” and “QA centralized” archetypes, may lead to micromanagement of site issues and burdensome levels of bureaucracy and governance. Some companies have found their centralization efforts weighed down by an ineffective global quality organization. The fault often lies with inadequate talent or insufficient investment in creating and enforcing global standards. In some cases, the company culture overrides the reporting lines; for example, a site manager may use operational priorities to overrule the quality department even if it has formal authority.

We find that high performers avoid the centralized model’s disadvantages by building strong leaders for the global quality organization. The top-performing pharmacos also develop pragmatic standards to ensure that guidance is thorough and is applicable to different local setups—detailed enough to allow consistent interpretation, but not too detailed to be inflexible. They strive for consistency and appropriate risk management when implementing global standards across the network, while empowering sites and making them accountable for improvement ideas.

Companies with a homogeneous culture should build local autonomy based on a strong culture of compliance and accountability. This can enable the organization to make decisions rapidly and without sign-off by senior managers. Success requires a strong emphasis on coaching and development, as well as mechanisms for strengthening the culture (including leadership involvement, the right kinds of incentives, and engagement forums).

For their part, companies with a heterogeneous culture that adopt a centralized model (typically during a crisis) already allow local autonomy. They should aim to develop clear, well-designed quality procedures and principles so that their sites can operate under consistent guidance.

Strengths and challenges of more decentralized models

Quality organizations that are integrated into manufacturing (the “site integrated, centrally coordinated” and “site managed” archetypes) are susceptible to compromised independence and incongruent systems. These organizations must be careful to ensure that their organization design maintains the independence needed for a compliant quality unit. Companies that favor decentralized models also struggle often with multiple quality systems, a scenario that increases complexity, allows multiple standards (which embeds risk), and leads to inconsistent metrics that make quality monitoring and learning difficult. At some of these companies, the process for escalating issues is also cumbersome and ineffective, increasing local “firefighting” and waste.

High performers that have integrated quality into manufacturing tend to have a strong compliance culture throughout the entire organization. Companies with successful strategies define high-level sets of metrics globally to facilitate monitoring; they also enforce global standards to increase process consistency across sites. At the same time, they give their quality units sufficient authority at the site level, and they establish well-defined interfaces between quality and technical operations at three levels: the site, local commercial affiliates, and corporate. Some companies have set up monthly meetings and other forums for sharing best practices.

WHY GOOD GOVERNANCE MATTERS SO MUCH

Good quality performance comes from the cross-functional alignment mechanisms that make any organization model work. If there is one factor that does predict the effectiveness of a quality organization, it is good governance. Our benchmarking study confirms that this is true regardless of the organization model.

Without strong governance, organizations often find that individual responsibility for making specific decisions is unclear and that the respective roles of sites and headquarters in decision making are poorly defined. In the absence of clearly designated authority, decisions delegated to lower organization levels don’t necessarily take hold. And without guidelines that delineate information requirements, the information presented to executives and managers is not sufficient for good decision making.

Strong governance extends beyond the committees and senior oversight and requires clear decision-making boundaries and effective execution across organization groups. Examples from strongly performing pharmacos point to specific behaviors and practices. These include the following:

- Aligning decision-making rights with accountabilities so that executives and managers don’t have overlapping authority;

- Requiring cross-functional discussions for decision making; organizational “silos” should not have authority to make decisions that affect other functions;

- Establishing clear rules for issue escalation from shop floor to senior management, combined with role modeling and empowerment of shop floor people to own and surface quality issues;

- Limiting participation in governance committees to only the stakeholders who have clear roles in the decision-making process;

- Ensuring that meetings adhere to high standards for “hygiene” (for example, minute-taking, quality inputs, and meeting practices).

Organization structure neither guarantees nor dooms the effectiveness of a quality unit. However, pharmacos have a far better chance of achieving world-class performance if they understand the pitfalls and success factors for each type of model. Further, there is no substitute for a good governance process. Effective governance is the function of any organization design, and it is entirely independent of how the “lines and boxes” of the organization are arranged.