Jobs and Salaries: Pharma's Professionals Piece Together the Future

After weathering a brutal economy in 2009 and a wave of layoffs in 2010 and 2011, it appeared that the drug industry, from a jobs perspective, was headed towards a promising 2012. Yet recent events—AstraZeneca announcing it will terminate some 7,300 employees worldwide, for example—have dented optimism. When asked what made him happiest about his job, one AZ employee who answered our survey this year lamented, “Nothing. I’m now redundant after 25 years of service.”

| Related Articles |

Make no mistake, things are still tough out there. The pharmaceutical industry is being buffeted by any number of “cross-currents,” making sweeping predictions dicey, says John Challenger, CEO of the recruiting firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas.

“Pharma continues to go through restructuring,” Challenger says. “Patents are expiring. The new U.S. healthcare law effects are still being seen. And there is still general uncertainty in the economy. This is leading to a new spate of layoffs.”

In other words, says Challenger, pharma’s great paradigm shift, transition period, or shaking out—call it what you will—will take a few more years. “We have plenty more to go before things get back to an equilibrium.”

And yet in spots, there are jobs, even plenty of them. “Boomtown” is what Megan Driscoll, head of Pharmalogics Recruiting, is seeing. Driscoll’s firm focuses exclusively on recruiting biopharma employees, with three-quarters of the business geared towards downstream manufacturing and Quality positions.

“We’ve seen unprecedented growth in our sector,” she says. “I’m dumbfounded at how incredibly fast it has come back.”

“There is wind in the sails of biopharma,” Challenger agrees. One of the cross-currents he refers to is a sudden wealth of venture capital for small to mid-size firms. Many can’t hire fast enough, or can’t find the right hires for their needs. Another factor, says Challenger: “FDA is opening up the pipeline a bit” and approving more new drugs.

That’s certainly good news compared to the doom and gloom (and more doom and gloom) of the past few years. Particularly in North America, manufacturing is on the rebound, and the economy has stabilized.

We also need to look at the entire workforce differently, says Alan Edwards, VP and product leader for Kelly Services’ Science business. “The life sciences workforce is transforming to one where individuals are in charge of their own career working for a company within the pharma supply chain as a contingent worker or ‘free agent,’” he says. “Many organizations are embracing this trend as part of their overall workforce strategy.”

Inside the Numbers

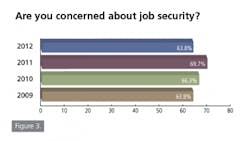

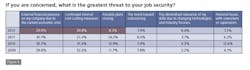

Our survey this year reflects a turnaround. One of the staples of our annual questionnaire is, “Are you concerned about job security?” After creeping up and towards the 70% “yes” mark for several consecutive years, that number has once again dropped, to 63.8% (Figure 3)—not exactly rosy but nonetheless a pendulum swing in a different direction.

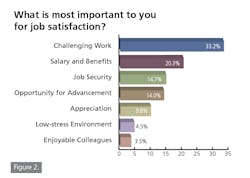

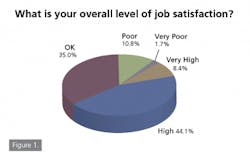

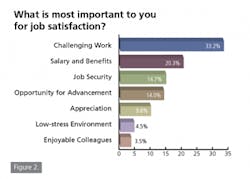

Other statistics are worthy of note. Your overall level of job satisfaction is slightly higher than last year (Figure 1). Fewer of you are anticipating potential plant closings, a good sign (Figure 4).

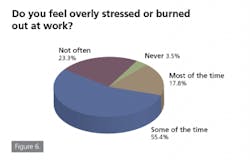

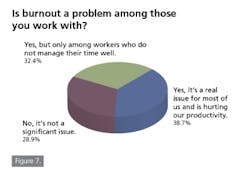

That same chart shows that roughly 50% of you have taken on an increased workload due to staff cuts. If there’s a silver lining, it’s that this percentage was 10% higher last year. The statistics in Figures 6 and 7 roughly correspond to what you told us in 2011—burnout continues to be a significant issue, for you individually, but also for your colleagues and site productivity.

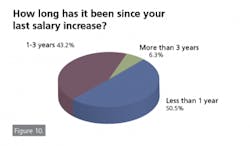

Another silver lining: Hiring and salary freezes have dipped over the past year, and fewer of you are expecting layoffs than last year (Figure 8).

A Tale from Pharma’s Front

So while many of the pieces of data in our survey in and of themselves are hardly cause for champagne, when compared to the past few years they offer some relief and encouragement. The future is brightening, though the present still a bit painful.

The experience of one long-time industry professional, who wishes to remain anonymous, illustrates the kind of cross-currents of which John Challenger speaks.

When the economic crisis hit a few years ago, “Mike” was asked to move from his long-time manufacturing operations position with a large biopharma company into a new role—the company valued and wanted to keep him, and he valued staying employed though the new position did not draw from his core skills.

A few years later, the company has embarked on an all-out leaning of its business and operations, predicated on cost-cutting across the board. The circumstances find Mike fearing for his job.While Mike understands his company’s rationale for leaning itself, he laments that fact that management at his facility is short-sighted. They’ve laid off personnel in key areas, increasing workload without offering perks or accommodations for those expected to pick up the slack. “Morale overall here is middle to low,” he says. Is site management aware of the problem? “I don’t think they see it,” Mike says. “We have a leadership team that is not open to hearing different ideas from what they believe. As a result, there is a level of fear to say what we think. That’s not something I’m used to. I have been vocal because that’s what I was used to at other companies. But I’ve been basically told by my boss to keep my mouth shut. So that’s what I do now.”Jobs for Hire?

From his perch overseeing what’s happening in traditional pharma R&D and manufacturing, Derek Lowe, who runs the popular In the Pipeline blog, is a cynic. “The big companies still appear to be laying off, and the pain doesn't seem to be anywhere near over at the ones with the biggest patent expiration problems” such as AstraZeneca and Lilly, he says. “The smaller companies aren't very cash-rich, to put it mildly, so they won't be able to soak up the excess completely. But I hope that the startup environment is getting a bit better; that's my only ray of sunshine these days.”

There has been a notable increase in new people joining the workforce in North Carolina, says Doug Drabble, director of North Carolina’s BioNetwork, which works with community colleges and Life Sciences manufacturers to train workers. “If someone is willing to relocate somewhere else in the state, we can usually put them in touch with five or six companies that are hiring.”

The openings are coming from manufacturers and other companies that are expanding and newly locating to the area. In addition, says Drabble, workers—middle managers, supervisors, floor operators, and maintenance professionals—are retiring. “You are seeing an attrition out of those groups,” he says. A good amount of what Drabble calls backfilling is taking place—employees at higher positions retiring, resulting in a cascade of internal promotions, leaving mostly entry-level positions open.

One of the reasons why North Carolina might see this phenomenon more than most regions is that it has programs such as the BioNetwork that help companies train incumbent workers inexpensively or even for free, supporting internal hiring.

The jobs that Driscoll of Pharmalogics is seeing right now are primarily in late-stage development. Positions hard to fill include those ranging from analytical development, formulation, and clinical development to regulatory and “anything in Quality.”

“We have lots of openings in California, and are expecting more openings in the next few months on the East Coast, from New England to the mid-Atlantic,” says Driscoll. All major biotech hubs are heating up, she says.

“Manufacturing is not dead, but it’s not robust,” she says. “But that cycle will change as products get approved.” Thus, while development and clinical jobs are hot now in the life sciences, manufacturing jobs will follow, and eventually drug discovery and early-phase research will make a comeback.

“Companies are focused and strapped for cash. They need to make the most of the drugs they’ve already discovered, and there’s not a lot of revenue being put back into research.”

Isn’t this a recipe for eventual disaster? “Yes, pipelines will be dry,” she says. “But the better firms will successfully acquire new drug candidates.”

Lowe isn’t so sure. “It's what the investors expect by now: the hardest cost-cutting possible. But even smaller companies that haven't gone public yet (or never will) are outsourcing pretty thoroughly, so it's clearly not just something to appease Wall Street. It really is too expensive to develop drugs, and companies really are trying to cut those expenses wherever they can.”

The big question is, how much is too much? “Problem is,” says Lowe, “you don't know you've cut too deep until you see blood.”

Going, Going, Gone?

Challenger, Gray & Christmas estimated that some 300,000 jobs were lost within the pharmaceutical industry between 2,000 and 2010 [1]. Challenger himself doesn’t believe that kind of fat-trimming will be duplicated any time soon. He also notes that layoffs do not necessarily mean overall job loss. “I do think there are places for people to go,” Challenger says. “Big companies are laying off and rolling out [employees], but people do go to work for smaller, more nimble companies that are finding niches.” Challenger adds that approximately 30% to 40% of those workers whose skills are transferable do indeed move to other industrial sectors when they are laid off.

Paradoxically, while drug manufacturers have been shedding staff, they are still looking for competent employees in certain skill areas. Some experts point to a “skills gap” that perplexes the industry. “There’s been a lot of talk about this,” Challenger says, “especially in what you might call semi-skilled positions” such as bench technicians and line operators. These jobs are going overseas due to wage pressures (i.e., it’s still much cheaper in places like India and China), or due to the fact that manufacturers in the U.S. are not finding enough qualified technical staff.

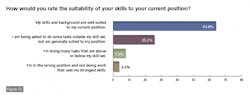

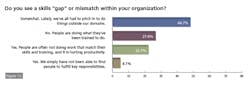

For the first time ever in our survey, we asked you a few questions about the suitability of your and your colleagues’ skills to the work that you do, and whether this is affecting productivity. Interestingly, only a small number of you felt that you were grossly mismatched to your position (Figure 12). Approximately one-quarter of you, however, felt that there was a significant enough skills gap within your organization that it is hurting productivity.

- “I try to provide training for our employees but with expenses so tight it is hard to accomplish.”

- “We are suffering from promoting scientists without considering their managerial or decision-making skills.”

- “We are experiencing a brain-drain. There are many new people without enough experience for the roles they were hired for.”

Mind the Gap

Like it or not, a skills gap is something that most every high-tech industry should expect to deal with going forward, says Lynda Gratton of the London School of Business [2]. Technologies will advance, eliminating semi-skilled positions especially. Demographics are playing a role, as Baby Boomers will retire in record numbers over the coming decade, taking with them the “deep tacit knowledge that has come from a lifetime of experience and which they have often failed to bequest to those members of Gen X who follow them.”

Finally, “the knowledge and skills that high-value jobs demand has shifted to engineering, IT and the sciences,” she writes. “This is good news for countries like Germany and India, where these disciplines are considered a good professional choice—but bad news for the UK and the USA, where fewer students take these options.”

The life sciences industry’s skills gap is actually smaller than that in other industries, says Edwards of Kelly Services. “More importantly, there is an unknown hiring gap between the candidate’s expectations of the position and the employer’s job criteria. Millennial recruits desire to be mobile and work from home and baby boomers are staying in the job market longer. Both types of candidates want to work for innovative companies and have meaningful assignments.”

Employers need to change their recruiting practices and source the work where the talent is located, he says. This is called “modular deployment.” Utilizing contingent workers is another way for companies to get the talent they need—the number of contingent workers is growing at a rate 25 times that of full-time workers, says Edwards.

In the Pipeline’s Lowe thinks manufacturers can use the supposed skills gap as an excuse. “If drug companies really are saying such things, it may just be window dressing, to make people less upset about all the outsourcing going on,” he says. “I think a more honest assessment would be for them to say, ‘We can't find people with the skills we need who will work for what we want to (or have to) pay them.’”

The opinion is supported by some manufacturing experts. “Some of the complaints about skill shortages boil down to the fact that employers can't get candidates to accept jobs at the wages offered,” says one. “That's an affordability problem, not a skill shortage” [3].

Manufacturers have to work a little harder, Megan Driscoll says. They need to offer more money, good relocation plans and other perks, as well as “lower their standards and be more flexible about hires.”

“Good companies find the candidates that have the right skills,” she says. “They pay for them.”

Vertex Pharmaceuticals is one example. “They have always been able to ‘flex’ a job specification and salary around a person,” Driscoll says. “Their success has hinged one-hundred percent on their ability to attract top talent. They can see past things that candidates might lack in technical skills.”

“It’s about finding a fire and a passion in someone” even if they don’t meet all the exact prerequisites for a job. “Many companies are very rigid and they miss 20 to 30 percent of candidates who would bring incredible skills to their organization.”

Major manufacturers are taking this to heart, says Drabble. “Companies are not looking for a perfect fit” in candidates, he says. “They want a fundamental fit.”

As an example, the new Merck vaccine facility opening this year in Durham will require some 800 new hires. “They’re looking for fundamental skills sets and then training these people internally,” Drabble says. “They’re not expecting individuals to have, for example, aseptic [processing] training, but they’re providing it the day the workers start.”

References

1. Herper, M. A Decade in Drug Industry Layoffs. http://www.forbes.com/sites/matthewherper/2011/04/13/a-decade-in-drug-industry-layoffs/

2. Gratton, L. The Skill Gap, Asian Style. http://lyndagrattonfutureofwork.typepad.com/lynda-gratton-future-of-work/2011/10/the-skill-gap-asian-style.html

3. Cappelli, P. Why Companies Aren’t Getting the Employees They Need. http://online.wsj.com/article_email/SB10001424052970204422404576596630897409182-lMyQjAxMTAxMDIwNTEyNDUyWj.html?mod=wsj_share_email_bot