Do You Really Understand the Tablet Press Overload Set Point?

One of the most misunderstood concepts of tablet press operation has to be the overload set point. Many compressing professionals assume it to be a key parameter, and mistakenly associate it with tablet hardness, compression force and even tablet weight. It’s not, in fact, a process parameter, but rather a safety value, designed to protect the tips of punches, the press operator and the consumer.

Defined as “that point at which the pressure upon tooling is so great that the machine must adjust or risk damage or breakdown,” the overload set point does not appear anywhere on a batch record or in many standard operating procedures (SOPs). However, failing to set it correctly may jeopardize an entire manufacturing operation.

This article discusses the overload set point, how it is correctly used and what it does and does not do.

Understanding overload events

In tabletting, powder is actually “squeezed” into a tablet by the action of one upper and one lower punch sliding along closing cam tracks and meeting together at a predetermined point in a die between the two main pressure rolls. That meeting point may be altered and the width of the “squeeze” changed by moving the lower pressure roll upward or downward. The result is called tablet thickness, while the force observed is the compressing force.

An overload condition, or “event,” occurs when too much material is placed in the die at one time; surprisingly, some of the material may not be the drug powder. Suppose that a bolt has shaken loose from a feed frame and entered a die. It may cause the tip of the tooling to fracture or break off. The operator can guard against this situation by correctly setting the overload set point. The tablet press or, with more modern machines, the computer, senses the pressure difference and adjusts to protect the tooling.

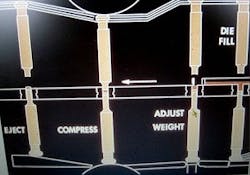

Figure 1 (above) illustrates a die being filled under a normal compressing cycle. When an upset condition occurs — such as when a tablet sticks to the punch or when that bolt falls into the die — there is the potential for an overload condition. Too much material is in the die, and something has to give. The pressure far exceeds a normal situation and probably exceeds the maximum allowable for the punch tip.

Other equally distressing events might also occur: a scraper bar could loosen and come off, and center itself over the die under the two punches; a loose bolt could be shaken off the press and enter the die cavity, or a tablet might jump into a feed frame, and be torn apart by the feeder wheels, and its pieces might enter multiple dies. Any of these scenarios will require quick response if the tooling, press operator and the consumer are to be protected.

Responding to an event

Figure 2 (at right) shows what happens when one of the events described above occurs in a machine whose overload set point has been correctly set. The press senses an excessive pressure and reacts. The two main pressure rolls then separate as the lower roll moves down, away from the other roll, relieving pressure and protecting the punch tips. The tablet is ejected.

The press can only adapt to the situation by comparing a predetermined input pressure to the actual pressure value, and either accept that value or back the lower pressure roll away. This predetermined pressure value can be input in a variety of ways. Some systems are hydraulic while others act on a “carriage” value or “support” value through the action of a spring. On older presses, the operator adjusts a large spring at the back of the press. Others, like the Manesty (Merseyside, U.K.) series, have a simple dial adjustment. All computerized presses accept a simple input value.

So the overload set point has no relation to tablet weight, hardness or thickness except in that rare case when the overload is triggered. In this case, the tablet will be thicker and softer than the other tablets because the press stopped at some point and the tablet was not fully compressed.

Determining the set point

There are various sources for the predetermined overload pressure value. Most tablet press manuals provide established calculations for standard round tablets. Some provide guidelines that account for pressure discounts due to letters, numbers and bisects. Other types of tablets, such as capsule- and oval-shaped, are calculated case by case.

The photo below is a page from a tablet press manual showing standardized round tablet diameters with corresponding maximum tip pressures. The arrow indicates a ¼-inch round, standard concave tablet with a tip pressure of 2 tons. For a deep concave tablet of the same diameter, the value would be 1¾ tons.

Manuals are not the only source of these values. Most drawings generated after 1999 that accompany new press tooling list them as well. The values are calculated on a punch-by-punch basis, since even upper and lower punches with the same shape may vary in pressure values if they have different combinations of letters, numbers and bisects. An important note: If a facility has an upper and lower punch with slightly different pressure ratings, it is standard practice to use the lower value of the two in order to provide the maximum protection for the set.

Setting the overload set point value

The overload may be set in more than one way, depending upon which type of press is being used. It helps to remember that the overload value is a one-time setting or input to the press for any number of batches being processed.

It does not change until the next product is placed on the tablet press. With computerized presses, this is a numerical value for input in a field. For older presses, a physical adjustment of a spring or counterbalance is required. The photo ;below shows how the overload value on the Kikusui (Kyoto, Japan) Libra is set by manually turning the dial.

Understanding and using the overload system correctly is one of many key factors involved in successful tablet compressing. The set point is not a critical processing parameter, but it is a very critical machine setting. It is not related to compressing force or tablet attributes and has no direct influence on tablet quality. And, while the predetermined overload value does not change how operators use different types of presses, it will vary from punch to punch depending upon the combination of letters, numbers and bisects used.