The Needle Gets Another Shot

By Paul Thomas, Managing Editor

As any pediatrician or parent knows all too well, nobody loves the needle, but rumors of its demise have been greatly exaggerated. Granted, companies are working hard on alternative delivery forms, and most patients would rather inhale a powder or swallow a pill than receive or give themselves a shot. Nevertheless, advances in technology and market conditions are giving the needle new life. Driving this renaissance for injectables are:

- The rise in biologics, which require the stability found in liquid or lyophilized formulations;

- New needleless injection and advanced syringe technologies that minimize the pain and difficulty of taking parenterals;

- Improved means of reconstitution and delivery of lyophilized product;

- The home-healthcare trend, which has spurred interest in pre-filled syringes a $5-billion market that could double within the next 10 years, according to the Freedonia Group (Cleveland).

For many drugs, the promise of newer and better delivery routes has failed to materialize. Most prescription products are developed as injectables with the hope that they may one day migrate to oral or another delivery route. But changing the drug delivery mechanism is extremely challenging, far more so than reformulation (see "Follow Your Nose: Taking Nasal-Delivery Drugs to Market" below), itself no easy feat.

Whats easiest for patients oral, nasal, buccal, transdermal is typically the hardest for drug manufacturers to provide, says John Paproski, VP of innovation for West Pharmaceutical Services (Lyonville, Pa.). By focusing on patient convenience, Becton Dickinson and other syringe providers have redefined the needle, even as new delivery technologies struggle for market share. One of the poster drugs of the new delivery methods, Pfizers inhalable diabetes treatment, Exubera, did not come to market quickly or easily, and will face intense scrutiny in its post-market period. In the meantime, more patients are relying on disposable pen injectors and a variety of syringes to get their insulin.

CMOs carry the load

Contract manufacturers, especially those who specialize in fill-and-finish operations, are increasing their capacity for liquid and lyophilized parenterals, improving their flexibility to handle small-, medium- and large-volume products, and minimizing changeover times to accommodate an increasing number of campaigns. CMOs have to be everything to everybody, says Joe Mase, group marketing manager of Baxter BioPharma Solutions (Bloomington, Ind.), a leading provider of fill-and-finish services for IVs, pre-filled and other syringes, injection cartridges and liquid and lyophilized vials.

Biopharmaceuticals are driving demand, Mase notes. More than 50% of Baxters business in Bloomington is for large-molecule drugs, many of which can now be administered in silicone-free pre-filled syringes. Baxters newest offering is the Clearshot, a copolymer pre-filled syringe that is molded from resins, cooled and filled on the same manufacturing line, all within a barrier isolator. Baxter operates one such line in its Cleveland, Miss., facility, and aims to have two lines operating soon, says Mase.

DSM Pharmaceuticals (Greenville, N.C.) is adding a clinical trial materials (CTM) sterile facility that will be commercially available this fall, and a suite for cytotoxics in 2007. Clear customer demand has driven both expansions, says Terry Novak, senior VP for marketing, sales and business development.

DSM is mulling a move into pre-filled syringes. Theres plenty of capacity out there, says Novak, but room for more CMOs to participate in the market. Ben Venue Labs (Bedford, Ohio), a division of Boehringer-Ingelheim, is also contemplating syringe filling. VP of operations Dave Henderson says he sees a definite shortage of contract syringe fill-and-finish operations.

Lyos share

Lyophilization capacities are also increasing. Ben Venue is currently in its fifth phase of construction since 1997, which, when completed, will add six new freeze drying machines by next year, bringing the total to 27. Eight of the dryers are in the cytotoxic and genotoxic suites, and we still have a lack of capacity, says Henderson. The cyto/geno arena is increasingly being contracted out, he adds.

Contractors play a guessing game in judging lyo demand, since drugs that are developed in freeze-dried form are often later stabilized as liquids Amgens Enbrel and Abbotts Humira are two examples.

DSM is also adding capacity. There seems to be a balance between supply and demand in the lyo market, Novak claims. What could throw that balance off is if a few major biologic products are approved over the next few years that exceed expectations.

Patheon is expanding lyophilization capacity at several locations and has created a development center of excellence at its Ferentino, Italy site. Drug manufacturers are often "forced into lyophilization" because their products cannot be formulated as stable liquids formulations or sterile powders that can be filled, notes Paul Turner, Patheon's director of business development in Europe. It chooses them.

However, there appears to be room for niche manufacturers to compete. Consider the filling of highly viscous liquids. Hyaluron Contract Manufacturing (Burlington, Mass.) whose name derives from its original product, hyaluronic acid specializes in this application. Getting drugs as thick as honey into syringe barrels is no easy task, says Rebecca Butler, corporate and legal affairs manager. The company plans to increase its 34,000-square-foot facilities by another 60,000 square feet in the next few years, she says.

Special delivery

If it werent for newfangled delivery devices, we might not be witnessing these trends. Syringe types are nearly as diverse as the drugs they deliver: disposables and reusables, pre-filled and vial-filled, single- and multi-dose of all shapes and sizes.

Becton Dickinson continues to lead syringe manufacturing innovation, and to influence filling and packaging. BDs Hypak SCF line is a standard bearer for the pre-filled market. The company has gradually mustered support for its Uniject, a filled pouch of plastic attached to a needle. Its a cheap, ready-to-use yet nonreusable device that is considered ideal for vaccine delivery in the developing world (see "Safety Guides New Syringe Designs," Pharmaceutical Manufacturing, April 2005).

Fill and finish for the Uniject is a radical departure from the norm. Inova, part of the Optima Group, has pioneered equipment and processes for the product. Luciano Packaging Technologies (Somerville, N.J.) offers table-top and low-speed (120-per-minute) machines. The empty syringe reservoirs are shipped by BD in large rolls like reels of film that are fed, filled, heat-sealed and coiled up again within the filling equipment, explains Howard Leary, Lucianos VP of engineering. The rolls are then fed into a finishing machine, which labels both sides of the pouches, cuts them into individual devices and inspects them for particulates and label accuracy.

Can Uniject make it in the major markets? Certainly, says Leary. Contraceptives and neo-natal tetanus inoculations are two possible applications, he says.

Prefilling lyophilized products

Freeze-dried product is also being pre-filled. Vetter Pharmas (Ravensburg, Germany) Lyo-Ject dual-chamber syringe separates powder and diluent in the syringe barrel with a stopper that gives way as the patient or healthcare professional screws the devices plunger, thus reconstituting the product. The challenge for Vetter, which fills the syringes in its contract facilities, is ensuring two aseptic fills in the same container, says Jeffrey Turns, president of U.S.-based Vetter Pharma-Turm, Inc. (Yardley, Pa.). Its an elaborate, automated process, one that involves filling, lyophilizing and closing off the drug product in half the syringe, flipping the syringe and replacing it in a tray for liquid filling and plunger insertion on the other end. The devices are then quarantined for contaminant testing.

There are few commercialized products delivered by Lyo-ject, admits Turns, but the potential is there for high-value lyo drugs taken at home, even with multi-dose capability.

Most pharmaceutical manufacturers prefer their vial-oriented lyophilization processes, says Paproski of West Pharma. To meet this demand while giving consumers improved access to freeze-dried product, West has developed the ClipnJect, a sterile syringe, pre-filled with diluent, that snaps onto a vial, allowing the patient to blend powder and diluent. You take six to eight steps out of the normal reconstitution process, Paproski claims.

Sterility assurance

The boom in filling technologies and capacity coincides with a tougher regulatory stance on aseptic processing, particularly from the EMEA. DSM spent three years and a fair amount of money to conform all of its small- and large-molecule suites to EMEAs sterile guidelines, says Novak.

Other global suppliers wrestle with EMEA standards. Ben Venue has reconfigured its facilities to meet the EU mandate of maintaining a clear segregation of product types within the same facility. The manufacturer now has dedicated spaces for cytotoxics, genotoxics, biologics and its ethical drug products, says Henderson.

Like many manufacturers, Ben Venue has integrated wash and sterilization tunnels into its filling lines, and is pursuing more advanced barrier technologies. FDA has been all too clear that it prefers such containment systems namely, restricted access barrier systems (RABS) or, even better, advanced isolators that prohibit operator access except through glove and RTP ports.

The dilemma is whether to take the small step to RABS or the giant leap to isolators. Ben Venue, which manufactures more than 200 products, is moving toward RABS for the flexibility it offers, Henderson says.

Most people start by looking at isolators, but back off to RABS, notes Jeff Jackson, director of product management and marketing for Bosch Packaging Technology, North America (Minneapolis). Manufacturers fear the validation implications of an automated decontamination cycle and not being able to open the isolator once a campaign begins.

In a way, RABS is a poor compromise, says Jackson. It requires personnel to gown up and use glove ports to operate machines. Isolators are going to be the only way to go 10 years from now, he predicts.

Were a contractor we took a half-step [toward RABS], says Turns of Vetter. Traditional laminarity works, he adds, noting that Vetter has had just one positive result in more than one million media fills.

We havent decided on our final configuration, says Novak of DSM. But, he says, we are probably moving toward RABS.

European manufacturers are leaning more toward isolators, says Matthias Poslovski, technical sales director for Inova and Kugler for the Optima Group Pharma.

Dispose of properly

Disposable components, popular in upstream processing, have slowly migrated downstream to aid sterile manufacturing. Tubing, valves, containers, fill nozzles and filters for filling are all available in disposable form. Millipore (Billerica, Mass.) is promoting its end-to-end, integrated disposable solutions, and will unveil a new disposable-dependent filling system at this months Achema 2006 show in Frankfurt.

Fill-and-finish manufacturers have been tentative to adopt disposables because they require equipment changes and thus validation work, says Millipores Jean-Marc Cappia, director of Mobius flexible bioprocess solutions. Cleaning validation is not an issue with sterile disposables, however, and the flexibility and speed they lend to operations have made them particularly appealing to contract fillers, Cappia says.

Patheon is embracing disposable equipment technologies, says Turner. For low-volume fills, it has invested in a new flexible filling line which includes a peristaltic pump filling system from Flexicon (Ringsted, Denmark), which compresses flexible tubing to generate fills. All product contact parts are then disposed of, and therefore no cleaning validation is required. The company's investments in this and other disposable technologies are primarily for clinical-stage manufacturing at present, says Turner. "As we take products through development, we'll want to take the advantages of these disposable technologies through to commercialization," he says.

Adding value with equipment

Equipment vendors are changing along with the times. Bosch, for example, has diversified its product line, which runs the gamut from machines based on piston pumps and rolling diaphragms to those incorporating time-pressure systems and mass-flow systems. While time-pressure systems are presently the most popular choice, says Jackson, the improved accuracy of the latest flow meters has made mass-flow-based machines a viable option. The company introduced a new line of nested fillers for the pre-filled syringe market at this years Interphex show in New York.

Customers are driving Boschs new offerings, Jackson says, and more and more that includes value-added features and solutions such as an enhanced documentation package to speed validation.

In the past, manufacturers would seek a specific line of equipment to match a given product. Nowadays, we have to supply machines and turnkey concepts, says Poslovski of Optima. The goal is time to market, and manufacturers are giving up trying to be specialists.

Contract manufacturers are also expected to provide the extras, none more important than current automation and control of operations. Where were really seeing innovation is in inspection technologies, says Ben Venues Henderson, whether enhanced systems for tracking particulates in liquids or clumping in lyo cakes, or weeding out faulty labels.

Automated inspection

"Automated inspection is probably the biggest part of our business now," says Leary of Luciano. The costs of vision systems and inspection technologies are down, while reliability is up, he explains, adding, "The reality is that you cant allow any false accepts, and dont want a high number of false rejects." Still, many applications will require a human touch. On the Uniject lines, for example, four operators are required to staff the video screens monitoring particulates within the syringe pouch, Leary says.

Bosch purchased Danish inspection equipment vendor Moller and Devicon two years ago and has since developed a full particle and cosmetic inspection system whose definitive feature is a lack of moving parts.

In-process control has also taken on added significance for sterile contract manufacturing. DSM offers control packages for liquid and freeze-dried operations. Its Lyo-Advantage, for instance, monitors 150 different critical process parameters (CPPs), and features continuous set-point monitoring, says Novak. Liquid-Advantage has similar benefits.

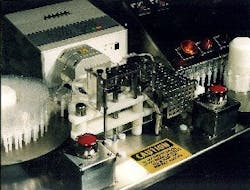

The Optima Group has developed in-process controls for fill volume based on high-accuracy load cells. Syringes are automatically removed 10 at a time from their nests, filled, weighed and replaced. The process not only improves on the time of manual weighing, says Poslovski, but also eliminates loss of sampled product.

Not everyone is automating everything. While many companies are switching to robotic tray loading for their lyophilization cycles, Ben Venue is one that is not. We manufacture 2- to 200-cc vials, says Henderson. The changeover time and amount of parts you need for automated loading doesnt make sense.