The Evolving Biopharma Contract-Manufacturing Market

Biopharma companies have depended on contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) to provide capacity and capabilities as needed; in some cases, CMOs have provided a great deal of a company’s production. Yet the current market structure presents biopharmacos with a shortage of CMO capacity to produce biopharmaceuticals, especially in mammalian cell culture technology and new modalities, even as demand for outsourcing increases. As companies face today’s evolving industry economics, they should first optimize their operations in order to free up hidden capacity. Once this is done, they have four remaining options: build, acquire, partner or face the realities of outsourcing.

WHY OUTSOURCE BIOPHARMACEUTICALS?

The large molecules that constitute biopharmaceuticals differ from small molecules not only in their size, but also in their behavior, their manufacture and the way they work in the human body. Manufacturing these molecules is significantly more complex than producing traditional pharmaceuticals.1 In fact, biopharma is a true high-tech industry, with complex processes that relatively few players have entirely mastered.

Perhaps as a result, the industry is more profitable than the pharmaceutical industry, with relatively little pressure on cost of goods sold (COGS). Biopharma has also grown steadily for a number of years, and the large pipeline of molecules in clinical trials promise continued growth.

Five factors are primarily driving this growth:

• Hedge risk: Biopharmaceutical companies often outsource to balance their risk and buy time until key milestones in clinical trials or market uptake are met and they can justify investing in-house.

• Lack of capacity: Many new market entrants. and start-ups developing biopharmaceuticals lack existing manufacturing capabilities. The same is true of some large pharma companies switching over parts of their pipeline to biopharma.

• Invest hurdles: The biopharma industry has high investment requirements. For example, a new biopharma plant with large stainless-steel vessels designed to produce high-volume biopharmaceuticals (500-1000 kg of active pharmaceutical ingredients, or APIs, a year) would require more than $250 million and lead times of four or more years.

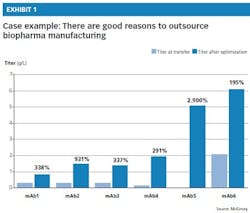

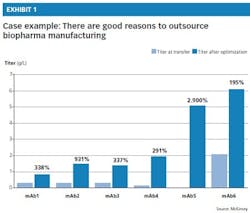

• Lack of capabilities: Several experienced CMOs have strong technical capabilities in cell line development, process development and scale-up. These CMOs are very well-suited to production process development, able to increase yields while reducing COGS. In fact, a CMO’s technical capabilities are one of the most important factors to consider when selecting an outsourcer, along with its track record of quality, compliance inspection and supply flexibility. Exhibit 1 illustrates one CMO’s success in increasing yields, or titers, after optimizing the manufacturing process for a range of six products (monoclonal antibodies, or mAbs).

• Technology shift: Two major trends impact existing mammalian cell culture facilities:

1)The production of large molecules moves to highly productive platforms composed of cell expression, media composition and process mode in up-and downstream processing (fed-batch vs. continuous, rise of single-use equipment). Not all existing plants are ready for disruptive productivity increase or use of disposables.

2)New biologics modalities in the pipeline like multispecific mAbs, viral vectors, oligonucleotides, peptides and other force biopharma plants into a multi-platform, multi-modality situation while most multi-product plants are still in a mono-modality and mono-platform setup.

THE CHALLENGES OF BIOPHARMA OUTSOURCING

Transfer complexity

Looking at the market drivers and the value proposition offered by leading CMOs, the advantages of outsourcing from a biopharmaco’s perspective seem clear. Yet biopharmaceutical outsourcing faces several challenges, one of the best-known — and most critical — is the molecules’ high transfer complexity. All large, complex biopharmaceuticals (such as mAbs, receptors and enzymes) require extremely sensitive production conditions given their complex structure and unpredictable post-translational modifications. As a result, transferring this type of biopharmaceutical to a new production environment is extremely complicated — whether transferring from R&D to manufacturing, or from the originator company to a CMO. In fact, more than a hundred input parameters must be adjusted to accommodate the living biopharmaceutical organism and the purification of large complex proteins, because duplicating the original environment is next to impossible. If transfers fail into highly utilized CMOs, the next slot available might be several months later, having a huge impact on the launch forecast and impacting the top-line, as such it is clear that an excellent process transfer track record is a critical success factor.

Nonetheless, some biopharmacos have mastered this and other challenges and found compelling reasons to use CMOs, including the CMOs’ strong processing capabilities, deep experience in production-process transfers, biomanufacturing excellence, high reliability, in-depth regulatory expertise, strong analytical capabilities and ability to adjust their facilities as needed.

Limited CMO capacity for large-volume biopharmaceuticals.

Beyond well-known challenges such as transfer complexity, biopharmacos face another pressing challenge if they are to outsource in today’s market: a shortage of CMO capacity, in particular for large-volume biopharma drug substances.

Today’s shortfall can be traced to three key factors:

• Although there are plenty of CMO competitors in the area of small molecules, in large molecules there are only 10 to 20 biopharma CMOs from which to choose, leaving limited options to biopharmacos seeking the ideal outsourcing partner.

• As of 2015, large-volume mammalian cell-culture production based on six or more 12kL bioreactor lines (the current industry workhorse) were offered by only three suppliers — Boehringer Ingelheim, Lonza, and Samsung — while others such as Patheon Biologics or Sandoz owned only one or two 12 kL bioreactor lines.

• Several players take an opportunistic approach to the market, acting as CMOs only when their own brands are not generating enough sales to utilize their full capacity. As a result, there is a risk that they may not offer very stable business partnerships, because they may prioritize their own brands when those volumes increase.

SWING FACTORS IMPACT CMO CAPACITY FORECASTING

Global cell culture utilization rate stayed relatively stable and rather high in the past five years at an average of 65 percent, while CMOs are presumably even at >85 percent. Going forward, the capacity utilization will diverge depending on dominate factors. Utilization goes up driven by: Biosimilar uptake in general, their expansion into emerging markets and comparably low productivity levels (in favor of similar product quality), demand increase for new therapeutic areas especially in unmet medical needs like immune modulation and CNS disease treatment, and general adoption of multi-specific mAbs produced by lower productivity expression systems. Utilization goes down driven by: second generation manufacturing processes that increase yield manifold, converting to ADCs ultimately reducing volume due to higher efficacy additional investments by CMOs, opportunistic CMOs and big pharmacos, a drop in clinical success rates and, finally, a shift to new modalities and treatments that push large molecules off traditional indications like oncology.

Evolving industry economics and new modalities

Adding to the challenge, we expect the economics for biopharma outsourcing to evolve over the next few years and thus further reduce CMO capacity. Although existing CMOs have been investing in large-scale capacity, they have only kept pace with existing needs and made no further expansions of any significance over the last few years. However, recently significant expansions by Lonza and Boehringer Ingelheim have been announced. Simultaneously, several formerly leading CMOs such as Boehringer Ingelheim and Celltrion Healthcare announced that they will rebalance their portfolios by adding to the development and launch of their own brands and biosimilars, even shifting away from contract manufacturing to do so.

Also, surprisingly few additional competitors are expected to enter the high-volume CMO market, despite profit margins of above 30 percent in the biopharma CMO business versus 5 to 10 percent in the pharma CMO business. The primary entry barrier is the high investment required — more than $350-400 million for a manufacturing facility with a capacity of six times 12kL and an additional $170 million for pilot facilities and labs — along with the development of enough skilled biopharma experts (likely in the hundreds) to manage start-up, biomanufacturing and product transfer.

As a result, only a few CMOs have the financial power and strategic direction to take on the risk of entering the biopharma market. One notable exception is Samsung, which entered the biopharma CMO market in 2013 with Samsung BioLogics. Wuxi Biologics is another rising player in biopharma CMO offering development and manufacturing in disposables based facilities.

The situation is likely to worsen for the production of next-generation biopharmaceuticals like antibody drug conjugates (ADCs), which require additional steps to make their active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) more effective in the body. Currently, no CMOs offer the conjugation technologies “one-stop shopping” — from drug substance supply, through conjugation, to drug product, which already account for 25 percent of the biopharma pipeline. Currently, there is almost no choice of CMOs for new modalities like cell therapy and viral vectors. Here, new manufacturing platforms and completely new ways for supply need to be established from E2E (e.g. personalized medicine).

Finally, with 83 percent of biopharmaceuticals consumed in the European Union and the United States, the industry’s high transfer complexity greatly limits the ability of biopharma companies to outsource to China or India, leading biopharma executives to view outsourcing there as less attractive than producing elsewhere, according to a recent survey.3 In addition to transfer complexity, of course, executives looking at China or India must take into consideration such issues as intellectual property protection, ensuring a high-quality product and gaining authorization from regulatory bodies such as the European Medicines Agency and FDA.

Without enough outsourcing options to meet demand, biopharmacos requiring large volumes have little negotiating power to help them capture value from a CMO. In addition, biopharmacos are in a weak position should they face capacity shortages, with little to no available internal backup production. And operating expenses tend to mount quickly, reaching $60 million to $80 million per year for 20 to 50 large-scale batches.

Small volumes

In contrast, CMOs operating on a smaller scale (up to 3kL) — whether for small volumes of biopharmaceuticals such as those needed for clinical supply or for small-volume commercial production, such as APIs for ADCs and biologics for niche indications — face fewer barriers to entry. The use of disposable reactors (up to 2kL) in particular has low investment requirements and therefore low entry barriers.

The value proposition of these smaller-scale CMOs will increasingly tend toward high-tech solutions such as high-expression cell lines (high titer) and next-generation protein purification (high-performance resins), which allow manufacturing on a lower scale (up to 3kL) and with high speed and flexibility. They are also starting to offer supplementary services such as production-process development or support for product transfers outside their companies, as well as the design and opening of disposables facilities globally.

Perhaps not surprisingly, therefore, market forecasts indicate a strong trend toward low-volume manufacturing as productivity continues to increase, biopharmaceuticals become more effective (requiring lower doses), and treat more niche indications. Nonetheless, we expect to see increased pricing pressure and consolidation, given that there are already quite a few small-volume CMOs in the market.

POTENTIAL STRATEGIC OPTIONS FOR THE NEXT 3 TO 5 YEARS

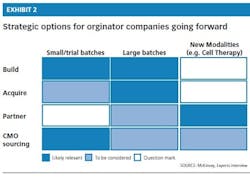

As biopharmacos face the myriad challenges of outsourcing, they have several strategic options to consider, whether they have existing capabilities — and expected future growth — or are just entering the biologics arena. These options include building a new facility, acquiring an existing facility, partnering with a large pharmaco and continuing to outsource despite the challenges (Exhibit 2).

When all optimization levers have been investigated, however, companies may still need to pursue other options.

1. Build

The first option will be to set up a new, large-scale facility. This option will require a substantial investment of time and money, but of the four options available, this one will ultimately ensure the most flexibility and control of supply and improve agility in launch situations. Over the course of a couple years, it will be financially attractive if the facility is built in a tech-advanced location, filled up and run with operational excellence.

To begin, a six-month macro-design phase will allow capacity and technology choices to be carefully developed, because decisions at this stage will affect capacity, flexibility and capabilities for the next 20 years. Another important decision during this period will be the location: the company must choose between proximity to its existing owned infrastructure and more aggressive expansion to new locations, allowing access to markets, talent or technology.

Next, a nine-month basic engineering stage will allow the company to gather more details on facility design, investment and future operating cost.

Finally, it will take approximately three years, from ground break to the first validation batches, for the plant to be market-ready. Keys to success during this period will include developing the right skills in engineering and manufacturing, establishing high-quality training programs for new hires and attracting experienced leadership.

Despite the amount of time and effort required, building a new facility will be the right choice for experienced biopharmacos with a balanced product portfolio on the market and a sustainable pipeline of products to be launched.

2. Acquire

Although the biopharma industry is on the rise, a relatively high number of assets sit idle owing to attrition in the product pipeline. However, acquiring these assets will not be an easy solution, given that the buyer will require certain in-house capabilities or else be forced to partner to gain these capabilities.

On the positive side, an acquisition would speed access to both capacity and talent, while potentially enhancing the buyer’s capabilities. A number of acquisitions have taken place in recent years, including the purchase of Amgen’s high-tech biologics bulk manufacturing facility by AstraZeneca4 and Baxter’s facility in Minnesota by Takeda.5 To succeed, a company must have the internal biotech skills to adjust its facility design, transform the acquired facilities and transfer its biotech processes.

On the downside, the existing facility design will often be too inflexible, requiring additional investments to adapt it to the necessary production process. In addition, facilities and a team sitting idle, for sale, for a certain period of time may result in the need to substantially remodel equipment and re-employ talent, along with the transformation of business processes and mindsets, before the facility can be useful again. Phasing out the previous owners’ systems and paying off liabilities while integrating existing networks will also be required, along with change management and product transfer. Finally, an acquisition of any size will necessitate a significant amount of the acquirer’s talent, which may be missed elsewhere.

3. Partner

A third option will be to take advantage of idle capacity within large biopharmacos. If the facilities have not been idle for too long, capabilities may still be strong and equipment well-maintained.

Partnerships work particularly well when the partners have a historical relationship or complementary skills that make it mutually beneficial. One example is the partnership that took place between Lonza and Genentech. Lonza built and launched a biopharma facility in Singapore and then Genentech transferred the production processes and took over the facility.6

On the downside, there is a risk that the new partner’s priorities will shift if its own molecules become successful, affecting the terms and conditions of the supply contract. There is the additional risk that large pharmacos will not be flexible in accepting existing contractual conditions, such as quality agreements. It is important to note that even large pharmacos sometimes lack experience with multiproduct operations and product-transfer excellence; as a result, the partnership could harm existing relationships and reputations.

4. Outsource

Large volumes: As described, the market structure is beginning to make large-volume outsourcing difficult, with few large-scale CMOs available. In addition, selection and management of CMOs requires appropriate organization and talent; the situation is quite different from that of chemical and pharmaceutical companies’ CMO relationships.

With such limited capacity available biopharma companies have little negotiating power and must either accept the conditions laid out by the CMO or choose another option, whether acquisition of assets or partnering.

Small batches and clinical supply: Originator companies may prefer to invest internally in low-cost assets such as disposables, particularly if they already have strong in-house capabilities for developing cell lines and production processes. However, for small batches and clinical supply, whether in-house or external, outsourcing is not difficult: enough choices exist to meet demand. This option would also be attractive for new entrants that lack basic biopharma capabilities but wish to learn the technologies and ensure speed to market.

Whether large volumes or small, outsourcing to a biopharma CMO should be considered to be more of a partnership and less of a pure supplier interaction. With this in mind, companies should consider establishing contractual agreements once a product is outsourced —agreements that allow them to learn and benefit from the opportunity by getting regular updates, aiming for joint production-process improvements, and gaining the right to send their own staff into the CMO’s facilities (called person-in-plants [PiPs]).

Biopharma contract manufacturing today faces steadily increasing demand because it offers biopharmacos both much-needed capacity and strong technical capabilities. At the same time, the large-volume CMO market expects capacity shortages over the medium term that will keep costs high and reduce the negotiating power of participants. As a result, companies should work to get the most from existing assets, introducing new technologies where available and taking advantage of any untapped capacity.

Where existing capacity is still insufficient, they must consider the four possibilities open to them: building, acquiring, partnering and outsourcing. Each option should be considered carefully; not every choice is suitable for every company. If, for example, a company can build on strong biopharma expertise, transformational skills, a lean organization and a global talent pool, then asset acquisition and partnering can be very promising alternatives. If the company lacks certain skills or a historical relationship with a potential partner, however, it may be forced to focus on the CMO market, seeking out scarce CMO capacity when moving toward biologics manufacturing.

RESOURCES

1) See the article, “Time for a New Prescription: Adapting to the Complexity of Biopharma Operations,” by Otto, Santagostino, Schrader.

2) High Tech Business Decision – Biopharmaceutical Contract Manufacturing Report 2012.

3) BioPlan Associates, Biopharma managers, survey carried out by HighTech 2012-2013.

4) https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2015/astrazeneca-biologics-manufacturing-boulder-colorado-11092015.html

5) https://www.takeda.com/news/2016/20160106_7262.html

6) “Roche and Lonza Announce Opt-in for Singapore Manufacturing,” August 31, 2009, http://www.roche.com/investors/ir_update/inv-update-2009-08-31.htm.