Authorized generic drugs are a bit like President Donald Trump — a magnet for controversy. Critics say consumers are harmed by authorized generics (AGs) because their entry into the market tends to delay the introduction of larger numbers of generic products. AGs also catch heat for contributing to a controversial practice known in the industry as “pay for delay,” in which a brand manufacturer pays a generic company to postpone bringing a competitive generic product to market.

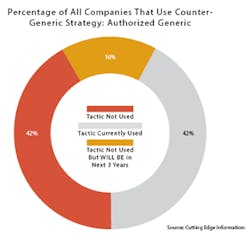

Also like Trump, AGs continue to be popular in spite of what critics say. There are about 1,000 currently marketed AGs, according to the FDA. Two out of five (42 percent) of branded pharmaceutical companies have used AGs as a competitive tactic, according to a 2015 survey by Cutting Edge Information, a business intelligence and research firm in Research Triangle Park, N.C.

Launching an AG remains an attractive solution for pharmaceutical manufacturers trying to extend the revenue life of drugs about to lose patent protection. The AG route — whereby a branded drug firm strikes a deal with a generic manufacturer to market a generic version containing the brand name product but with different packaging and labeling — enables branded companies to extend the revenues of a drug going off patent.

Typically the branded firm agrees to permit the authorized generic in exchange for either a one-time fee or a portion of the AG revenues. As an alternative, the branded firm may engage its own subsidiary to manufacture and sell the AG. That was the case when Novartis decided to market a generic version of Lotrel through its Sandoz division.

Unlike a regular generic that requires an abbreviated new drug application (ANDA), the AG is marketed under the original NDA for the branded drug. As a result, AGs aren’t subject to the Paragraph IV regulations granting 180-day exclusivity to the first generic company to file to enter the market.

FIRST-FILER VERSUS AG

The upshot is that the AG can compete with the first-filer generic, which ultimately serves as a deterrent to other generic companies looking to tap the market early. For example, after Eon Labs launched a generic version of Astra Zeneca’s Toprol-XL heart drug, AZ brought out its own generic via an agreement with Par Pharmaceutical. Not surprisingly, this added competition can result in lower prices. “Having two players in the market helps to bring the price down during the 180-day exclusivity period,” says Dinkar Saran, Partner at PwC.

Without question, tens — if not hundreds — of billions of dollars in revenue are at stake each year as the industry’s blockbuster drugs — often with sales in the $5 billion-and-up range — approach their patent cliff, allowing the influx of lower-priced generic competitors.

“When these branded drugs go off-patent, they are not going to retain anywhere near their former revenues,” says Eric Bolesh, senior director of product development at Cutting Edge Information. “With the authorized generics, the pharmaceutical innovator firm is trying to delay the inevitable.” He cites the case of a top 10 pharmaceutical company (a participant in the research firm’s blind study) that had a drug with $4 billion in global sales going off patent. “An authorized generic enabled them to generate an additional $500 million in revenue,” Bolesh says.

OTHER OPTIONS BESIDES AG

Of course, pharmaceutical companies may elect to eschew the authorized generic option, choosing instead to pursue some other alternative aimed at extending product life. For instance, one way is to reformulate the product to extend its patent protection by obtaining a new indication for the drug. Or the company may develop a next-generation follow-on drug to the original one going off-patent.

“There is a lot they can do to beef up their offering or delay the generics’ introduction into the market,” Bolesh points out. “Our study found that the branded pharmaceutical firms look at various counter-generic strategies to preserve as much lifecycle income from a product.”

From a manufacturing viewpoint, an AG is produced exactly the same as the original branded drug, except for different packaging and labeling indicating it’s a generic of the original brand. Often the AG manufacturer will take the branded firm’s inventory and repackage it as the brand’s new generic. And in some cases the AG may compete with the original brand drug.

Deals to market an AG can arise from a variety of differing market scenarios. One way is when a generic company files a Paragraph IV certification, challenging the branded firm’s patent. If the branded company wants to avoid litigation or the loss of a patent dispute, it may offer to make a deal with the generic company to produce the drug during its 180-day exclusivity period. Some authorized generics deals emerge following a Paragraph IV court dispute, in which both parties deciding to settle out of court. In effect, the legal challenge allows a generic firm that can develop a cheaper version of the product to break the patent early.

MYLAN'S EPIPEN AG

Since generic companies are accustomed to marketing to large buyers of pharmaceutical products such as hospital groups and other wholesalers, they can tap new markets for the AG. “The AG company may be better able to distribute those drugs to patients because they operate in different markets,” observes Scott Myers, senior managing consultant with Tunnell Consulting in King of Prussia, Pa. “Typically with generics they are not calling on physicians like the branded firms do, but instead on large purchasing organizations that can distribute the product, resulting in a better price for the patient.”

Others agree that navigating the generic waters is different from swimming in the branded pool. “The branded drug innovators are not used to working in that supply chain,” says Jimmy Boyle, managing director in Pharmaceutical and Life Science at PwC in New York. “The generics are channel plays and trade plays - they focus on wholesalers, GPOs, hospitals and large chain pharmacies, rather than patients.”

Although AGs often are seen as anti-generic by those in the generic pharmaceutical industry, this isn’t always the case. “For the generics company that signs a deal to produce an authorized generic, it’s a tremendous asset, because they can then wrap up early deals with hospital chains and other large customers,” says an executive at a large branded pharmaceutical company who preferred to remain unidentified. Adds Saran of PwC, “For the generic company, if they aren’t the first to file, it’s their way of getting into the market. Being first on the shelf is important.” For the branded drug company, it’s a way to continue a significant revenue stream before the product comes under the full pricing pressure of a slew of generic competitors.

In the three months before a product goes off patent, the large buyers will stop ordering, will have exhausted their inventory of the branded product, and have already purchased large amounts of the first-filer generic product, the pharmaceutical executive explains. But launching an AG can help avert this scenario. “The authorized generic is a win-win for the branded company and the generics company that makes the authorized generic,” he adds.

POST-EXCLUSIVITY REVENUES

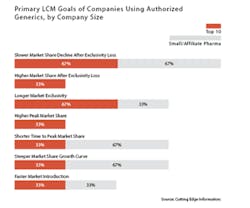

Indeed, branded drug manufacturers often are able to sustain a significant, if declining, revenue stream from an AG for some time beyond the date of patent expiry. For instance, slowing the market share decline after the loss of exclusivity was cited as the primary product lifecycle management goal of using an AG by two-thirds (67%) of companies in a survey of top 10 and small pharmaceutical firms released in December 2015 by Cutting Edge Information.

Because the launch of an AG comes near the end of a drug’s lifecycle, pharmaceutical companies tend to avoid tooting their horns about it, for obvious reasons. “There is sensitivity around the authorized generic because it’s not an exciting approach from the perspective of the branded manufacturer, as far as innovation goes,” Bolesh points out. “At this point they may be 10 years on in the product’s market life. In effect, they are waving the white flag.”

From a revenue standpoint, however, AGs offer at least a green pasture, if not a fully fertile field to plow, as AG prices tend to offer a limited discount from the original version. “During the 180-day exclusivity period, they don’t want to charge a super-low price,” Bolesh says. “Why would they?” In other words, with the only potential competition being a generic first-filer — if there is one — the authorized generic brand tends to take only a partial hit off the original branded drug’s price.

Clearly, the practice of leveraging an AG to continue to reap significant revenues from an older drug about to go off patent has its adherents. “The innovator drug company has invested a lot of money in developing, manufacturing and marketing the product, and it’s their choice to pursue a financially advantageous opportunity during the 180-day exclusivity period,” says Boyle.

The cost of implementing an AG strategy tends to be small when compared to the amount of revenue left on the table when a major branded drug nears its patent expiration. Among the companies surveyed by Cutting Edge Information, the cost of AGs deals ranged from a low of $250,000 to a high of $5 million. For every dollar spent on an AG, drug companies received $51 in return, effectively an ROI of 5,100 percent, according to the research firm’s study entitled “Pharmaceutical Lifecycle Management: Expand and Extend Portfolio Value with a Well-Integrated LCM Strategy.”

PAY-FOR-DELAY

“Settlements in which the brand-name company agrees not to compete with an AG have become commonplace,” the FTC report states. “Moreover, as a consequence of an AG’s significant negative impact on a generic’s revenues, some brand-name companies have used agreements not to launch an authorized generic as a way to compensate an independent generic in exchange for the generic’s agreement to delay its entry,” the report continues. “The frequency of this practice and its profitability may make it an attractive way to structure a pay-for-delay settlement, a practice that causes substantial consumer harm.”

One out of four (39 out of 157) patent settlements with first-filer generics contained such provisions, the FTC report found. The average delay for the 39 agreements was 37.9 months, and the total market for the drugs involved exceeded $23 billion. In fact, it is the promise to suppress AG competition — not the AG itself — that the report said was responsible for any resulting harm to consumers stemming from higher drug prices.

To the contrary, the FTC report concluded that “during the 180-day exclusivity period, competition from authorized generics lowers prices for consumers and lowers revenues for the independent generic competitor.” The FTC indicated that competition from an AG during the 180-day exclusivity period is associated with retail generic prices that were 4 to 8 percent lower and wholesale generic prices 7 to 14 percent lower than prices without authorized generic completion.

Average retail prices for a typical generic drug during the 180-day exclusivity period were found to be 86 percent of the pre-entry brand price without AG competition and 82 percent of the pre-entry brand price when the AG was in the market. Similarly, the average wholesale price of a generic drug during exclusivity was found to be 80 percent of the pre-entry wholesale price without the AG, and 70 percent when the AG was present in the market.

It’s no wonder generic firms tend to look dimly upon AGs, since they serve to delay the onset of full-on generic competition, thereby reducing generics’ revenues. The FTC report estimated that having an AG in the market trims the first-filer generic firm’s revenues by 40 to 52 percent.

Nor does the impact on generic manufacturers end when the 180-day exclusivity period is over. The revenues of first-filer generics in the 30 months following exclusivity average between 53 and 62 percent lower when forced to compete against an AG. “Almost all AGs marketed during exclusivity continued to be marketed for an extended period,” states the FTC report.

NOT AN EASY DECISION

The decision to launch an AG isn’t taken quickly. On average, pharmaceutical manufacturers take 21 months from strategy planning to execution of an AG launch, according to the Cutting Edge Information survey. Because AG deals usually are struck either when the drug goes off patent, or when a generic company files a Paragraph IV certification, the stage during which the branded company begins planning for an AG varies depending on the circumstances of each drug.

When structuring the deal, the branded drug company holds most of the face cards. “Normally a generic company might get 20 to 30 percent, with 70 to 80 percent going back to the innovator,” Boyle says. The generic company’s share may not sound like a lot, but as Boyle puts it, “It’s 20 to 30 percent of a fairly large number, versus otherwise getting essentially nothing. And from the innovator’s standpoint, it’s a nice proposition, because they don’t have to focus on a market they don’t normally deal with.

“The authorized generic is a really good approach for the branded drug company,” Boyle says. “After spending hundreds of millions of dollars to develop and launch that drug, you want to do everything you can to protect that asset and benefit from it. You don’t want your baby to go away quietly.”