Three-Step Quality Network Transformation: A Case Study

Pressure on pharmaceutical quality functions is increasing, from all sides. Regulators have bigger budgets and a more aggressive approach to inspection and enforcement. The direct financial impact of quality issues can run into the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, but pharma companies can’t afford to tackle theses issues by throwing huge amounts of money at problems. Faced with a shortage of high-value new products, spiraling R&D expenditure and aggressive competition from low-cost market entrants, they must learn to do much more with much less, calling for a step-change in efficiency from quality assurance functions.

But even unearthing the key issues and opportunities for performance improvement can be difficult across a global network of plants.

When the FDA demanded that it shut down one plant and issued warning letters to several others, managers at one global pharmaceutical manufacturer knew they had to define innovative ways to uncover the root cause of their quality issues. High-level benchmarking could give an overview of the performance of different plants, but would do little to indicate where the company should take action to improve performance. While individual quality processes are relatively simple, the overall effectiveness of a quality system relies on complex interactions between hundreds of separate actions, and a considerable amount of human judgment. The failure in a single process or a single interface between processes can have profound consequences.

Detailed investigations of every individual plant, on the other hand, would identify action points but would take too long. Instead, the company adopted a hybrid approach, combining the breadth of global benchmarking and the application of modern risk management tools with the depth of focused diagnostic assessments in selected sites.

First Step: Taking the Global High-Level View

The first step was building a high-level picture of the fitness of the company’s quality function, using benchmarks to compare its current performance to that of industry peers, and to identify the variation of performance between its own plants.

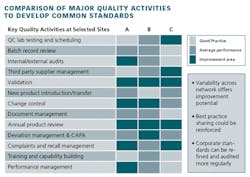

Out of 13 key quality activities investigated, the company measured the effectiveness of quality activities by examining the recurrence rates of issues, indicating a failure to get to the root cause of issues. It studied efficiency by looking at the number of worker-days devoted to each quality issue.

Some plants had such inefficient processes that a single quality deviation would absorb considerable resources, while others devoted very little to each problem, suggesting a tendency to go for fast fixes instead of attempting root cause analyses.

Beyond the specific benchmarks, this effort also revealed some important basic issues. Another important aspect of the high-level view is the risk evaluation—understanding the relationship between current performance and potential future quality risks.

Second Step: Focused Assessment of Selected Sites

For deeper analysis, the managers selected three sites which stood out from the others, either due to a particularly high value at risk, strategic importance, or because they were recognized as having exceptionally good quality performance. It dispatched an evaluation team to investigate those sites. The 15-strong team included senior quality managers from all of the company sites worldwide, together with specialists from the local and central quality functions to provide assistance collecting and analyzing data.

Because the members of the evaluation team had the results of the benchmarking and risk analyses, they could focus their time and attention on the processes in the plants that gave the most cause for concern, or on those that seemed to perform much better than those elsewhere (Figure).

About the Authors

Nicolas Esmaïl ([email protected]), Lorenzo Positano ([email protected] ) and Vanya Telpis ([email protected]) are leaders in McKinsey & Company’s Pharmaceutical Operations practice.