This is the fifth year that Pharmaceutical Manufacturing has surveyed readers on their automation and process control practices. This year, 102 people shared their views. Results suggest that little has changed during this period. In fact, if this year’s responses are any indication, resistance to such FDA-supported initiatives as Quality by Design (QbD) and Process Analytical Technologies (PAT) continues to be seen, due to cost and time concerns.

In this article, we summarize this year’s key survey results and compare them with results from previous years. These are not direct comparisons because the survey questions and format changed slightly from year to year, but some trends are still visible. Pharmaceutical manufacturers’ use of process capability analysis and statistical process control appears to be growing but far from widespread.

Other trends include:

- Increased interest in continuous processing

- Better overall alignment between IT and process control operations and operational excellence goals

- Slowed installation of new technology platforms, such as manufacturing execution systems (MES), due to plant closures and off shoring of operations

- Increasing use of wireless monitoring, with greater interest in process applications.

We asked readers whether continual improvement and operational excellence programs such as Lean Six Sigma were guiding, or at least in synch with, automation and IT goals. This year, 16% of respondents said this alignment was a top priority, down from 19% last year; however, 26% said they had achieved some level of alignment, up from 15% in 2009 (Figure 1).

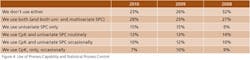

We asked about PAT and the broader Quality by Design (QbD) approach and whether companies were implementing either or both approaches. Our first survey, in 2006, was published roughly two years after FDA published the PAT guidance, and before QbD was formally introduced. At that time, 20% of respondents said they did not plan to implement PAT. This year, 32% said they had no plans to implement either PAT or QbD; cost and time were the greatest obstacles (Figure 3).

There are many reasons for reluctance, said consultant Pedro Hernandez-Abad, who had championed PAT and QbD at Wyeth before and after the merger, and who spoke about some of these issues during a recent PharmaManufacturing.com webcast. First, there’s fear of change, and a loss of control. “When quality moves from lab to the manufacturing line, there’s a learning curve,” he said. “QbD and PAT cannot be done part-time. You need to have champions who can drive the effort, but the big question is, ‘How much is it going to cost?’ ” he said.

“If I put $500,000 into equipment and training, I need the money back by the end of the year. But with new approaches such as QbD, an exact number is not always possible to predict,” he said. More and more companies are doing real financial viability studies for PAT. However, there are hidden costs, Hernandez said, such as support systems. “You’re not just talking about an instrument on the line but an IT infrastructure and meaningful sampling strategies,” he said. Finally, there’s the question of which metrics will be most meaningful for a whole new approach.

QbD, From the Ground Up

“A lot of folks are trying to push QbD through their organizations. They oft en stress the idea of regulatory relief and real-time release,” said PRTM principal Sam Venugopal. “But it can require some significant investments to get to that point.” Some companies are breaking the problem down into increments, he said, asking, for example, “Can we look at how we are capturing information within our organization, and, at a minimum, understand our processes better . . . and maybe get to regulatory filing faster?”

J&J’s Pharmaceutical R&D is building QbD from the ground up, says Paul McKenzie, global head of pharmaceutical development and manufacturing sciences. At this point, he said, “We’re ensuring we have the pillars to make QbD successful, but we need to invest in those pillars, first, before we prescribe doing QbD across our whole portfolio,” he said. “Our manufacturing and development groups agree that we need to define platforms and technology to get the same base vocabulary across the two areas. As we do that, we can than start driving, internally, the business case for QbD,” he said. “Then the question becomes: ‘How do we convince ourselves and regulators that we have a firm understanding of our complete design space?’ That then allows us to consider different approaches to product portability, process and/or raw material changes.”

The first step, McKenzie says, is establishing the foundation for a platform with each area. “Once we have a continuum of information, we will need to marry that space with the clinical space, so we can really dial in on the impact that process changes will have on safety or efficacy. If we can build that integrated process, analytical and clinical design space, it will make it much easier for us to adopt and make a strong business case for QbD.”

Deming, or Damning?

Thinkers within industry and FDA who had encouraged pharma’s use of modern industrial engineering techniques say there has been little change since Ray Scherzer made his benchmark presentation on QbD to the FDA in 2002. “At this point, we have to ask, is it Deming or damning,” joked U.K.-based consultant Ken Leiper. This year’s survey results suggest slightly greater use of process capability analysis and statistical process control, but univariate SPC dominates, even though drug manufacturing is multivariate (Figure 4).

In order to do either SPC or CpK correctly, extensive sampling is needed, as well as reasonable specifications, said consultant Ali Afnan, formerly with FDA. “In most companies today, testing is done post-production,” he said, “Every individual manufacturing step is tested after the step is complete. This is true of small molecules, in operations such as blending or drying, and in large molecules, in fermentation and cell growth.” Significant testing will indicate variability in the product, he explained, but at this point the process is, typically, already “validated.” Now, the only way to achieve results is to improve the process, but the three-batch validation approach makes that a frightening prospect for most manufacturers.

“If the same process were applied to finished goods such as tablets, batch after batch would be rejected,” Afnan said. Once 10% of batches have been rejected, revalidation will be needed. As a result, Afnan added, industry has been crippled. “Companies hurry to get a submission in but have not seen problems, because, if they see them, they must act, triggering a lengthy prior approval supplement with FDA.”

The industry’s data management practices don’t help, says Arvindh Balakrishnan, VP, Life Sciences, Industries Business Unit, Oracle Corp. “The pharmaceutical industry has a big challenge with aggregating the required information,” he said. “MES systems, by definition, serve at the manufacturing plant level, but there is very little standardization of MES level information across plants.

In addition, MES systems are oft en viewed as having mixed results on ROI, while systems, processes and even people are oft en constrained by silos created during acquisitions and divestitures.” In such fragmented environments, Balakrishnan said, it is hard to implement global multivariate approaches. Nevertheless, readers whose organizations are using the tools swear by them. “We conduct process capability analysis annually, as part of our annual product review,” wrote one.

Installation of MES is down this year, respondents say (Figure 5), due to concerns about integration with existing IT as well as overall return on investment. “We’re using individual modules but have not moved to an integrated system yet,” wrote one.

“Strictly speaking one could operate with a paper system,” said Afnan, “but the efficiency of asset utilization will be very low.” For example, one would have to keep track of every piece of equipment to know when it is ready for use, and when it needs washing, he explained. If you are not fast enough because you’re using a paper-based system, then you have to build in redundancy, which requires investment.

Implementing MES really depends on the level of automation that a company wishes to pursue, said Oracle’s Balakrishnan. “MES offers close integration between real-time control systems, machines themselves, plant inventory and labor systems. But this makes sense only if you plan to take advantage of this integration,” he said. He suggests asking yourself the following: How serious is your organization about QbD? How many PAT related submissions have you made? Are you incorporating supplier raw material quality into your own production plans and process control mechanisms? Do you have a comprehensive view and definition of quality across the various dimensions that could affect the drug’s overall performance in the patient’s body? “The more you tend to answer ‘yes’ to these questions,” he said, “the more likely you are to get positive ROI from MES.”

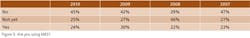

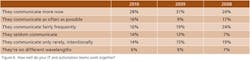

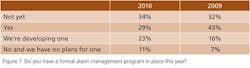

Readers’ top process control goals were improving data quality, to enable process modeling and optimization. Following closely on their priority lists were moving to paperless batch recordkeeping and developing trending data for equipment and batch manufacturing. Respondents say that integrating maintenance and manufacturing data, and integrating data from field sensors to the plant floor are “very important” goals this year. Collaboration between IT and automation teams seems to be improving, too (Figure 6), while alarm management is receiving less emphasis (Figure 7).

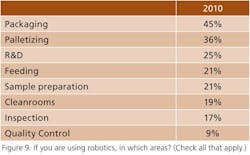

Interest in wireless monitoring appears to be increasing slightly, particularly for process operations (Figure 8), robotics is being applied mainly to packaging (Figure 9), and more respondents say they are adding continuous processing capacity to a batch base (Figure 10). However, such efforts may depend on the success of “champions.” Wrote one respondent, “The person who advocated continuous processes at our company left after he failed to get management support.”

To date, we have used FDA’s improvement initiatives from 2002-2006 as the basis for these surveys. Static results suggest that perhaps the focus should change, and questions should be a more open-ended. What tools are you using in your organization to increase the level of process understanding and control? Please send any comments or suggestions you might have.