Dr. Michael Meagher has been planning his dream home for nearly two decades. Only this home isn’t where he lives, but where he works—on the lower levels of Othmer Hall on the campus of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, his employer since he left Hoffman-LaRoche in 1989.

Under Meagher’s direction, UNL has built one of the top biopharmaceutical research facilities in academia, the Biological Process Development Facility. The BPDF has had GMP capabilities in its past, but the latest incarnation, set for its ribbon-cutting this winter, is the culmination of his dream—a state-of-the-art pilot-scale plant with core competencies in the development of vaccines and therapies from recombinant yeast and bacteria.

Meagher will have what he calls “an academic CMO on steroids,” able to develop robust Phase I and II trial products and technology transfer. He has built it. Now, will they come?

The Tour Begins Here

The BPDF already has quite a reputation. It has worked with the Department of Defense for 14 years to develop processes to manufacture vaccines against bioterrorism agents. For one of its other clients, the BPDF is producing a Phase I recombinant subunit injectable vaccine.

The BPDF has made a name for itself in fed-batch fermentation and downstream processing of recombinant proteins from the methylotrophic yeast, Pichia pastoris, a protein expression system that utilizes methanol as an inducible carbon source for recombinant protein production. While not as fast as E. coli, Pichia pastoris has proven to be an effective system for proteins that are often very difficult to express in E.coli. The BPDF has extensive experience working in both systems.

The new facility is modest in dimension—24,000 square feet, with 12,000 square feet for process research and development, 5,400 square feet of new modular cleanroom processing space, 600 square feet for a modular cleanroom QC laboratory, and 6,000 square feet of GMP utility area.

Nevertheless, the facility includes:

- A 1,200-square-foot fermentation suite with a 200-L BioEngineering bioreactor. (The suite can handle a 1,000-L reactor should someone want it, Meagher says.) The suite features a methanol-handling fume hood because of the plant’s emphasis on methylotrophic yeast. The fermentation suite will be able to harvest by either membrane filtration using two NCSRT Model 50 membrane filtration systems or an Alpha Laval LAPX 404 centrifuge. There is also the capability for cell disruption using either an APV Gaulin homogenizer or Microfluidizer.

- A class 10,000 purification suite of 900 square feet with a built-in, 100-square-foot class 10,000 cold room. The suite is equipped with an NCSRT 6 L/min chromatography skid and NCSRT Model 10 and Model 5 membrane filtration systems.

- An aseptic processing suite outfitted with a VHP-sterilizable Class 10 isolator system, designed by Containment Solutions, Inc. and built by ConeCraft, Inc. to handle Master Cell Banks and Working Cell Banks. The isolator system is a one-of-a-kind built specifically for the BPDF. Along with the main five-glove isolator are two four-foot “isolets” that are used as class 10,000 incubators and can connect with a control panel on the wall to maintain temperature and humidity within.

- The remaining key spaces include an airlock that exits the three suites, dirty and clean staging areas, and a buffer prep room with a 500-L tank.

Operator movement around the facility will require certain gowning considerations, and the dirty staging area will be accessed from outside the cleanroom space through the main building corridor—concessions to working with a small footprint. “We just didn’t have enough square footage to do exactly what we wanted to do,” Meagher says.

That’s not to say that, like any dream home, the BPDF doesn’t have its share of extravagances. (See below.) One is a curved bank of windows within the aseptic suite that faces an atrium area with its own windows to the outside world. “The person working in the isolator is literally three feet from the window,” Meagher says.

Meagher likes windows for transparency. He wants the general public to see what is happening inside. The purification suite has glass windows on two sides along the main corridor of the first floor of Othmer Hall and people walking outside the building can look through the same windows into the purification suite. There’s another bank of windows on the second floor where passers-by can see all of the process piping and ductwork for the HVAC system. “Just imagine a big engineering drawing on the wall in a nice frame, color-coded, and then the ductwork that you’ll be looking at will also be color-coded,” Meagher explains. “You can go in there and give a tour, and sit there and play the game of looking back and forth to see which duct goes where.”

Room with a view: A curved bank of windows allows viewing from a common building corridor (and outside the building) inside the aseptic processing suite and its new Class 10 isolator.

Going Modular

Meagher’s vision has had technical grounding from engineering specialists. AES Clean Technology, Inc. (Montgomeryville, Penn.), with its expertise in modular cleanroom design and construction (think Cook Pharmica’s new Bloomington, Indiana biotech plant), and Biokinetics, Inc. (Philadelphia, Penn.), a specialist in biotechnology and pharmaceutical process systems, worked with Meagher even before funding was approved.

“We’ve been able to do a lot in a very small space,” says Grant Merrill, Director of Project Development for AES. “Dr. Meagher spent years on this layout—he came to [AES and Biokinetics] with a good plan which required only slight modifications. It’s a tribute to him.”

One thing the project had going for it was modular construction. AES’s system of cleanroom construction involves fabricating the architectural building blocks—walls, ceilings, air cavities, doors and windows—in the company’s Atlanta manufacturing facility but assembling them in the field. The process saves time but offers flexibility and precise finishes as well.

Modular made sense from a budget perspective. Academic projects require special considerations in regards to funding. Money does not come easily or quickly, and the purse strings are usually controlled by various committees. Once approved, there is no room for add-ons. “Ultimately, our contract was firm,” says Merrill. “The pressure was on us to stick to it.”

“I received a stick-built cost [estimate] about six years ago, and then later I developed a modular cost that was dramatically less,” Meagher says. “What was initially a $28 million project was trimmed down to an $11 million project, and with pretty much the same capabilities that we had outlined six years ago.” As it nears completion, the project is within budget.

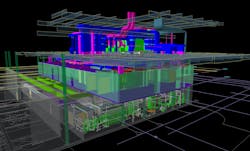

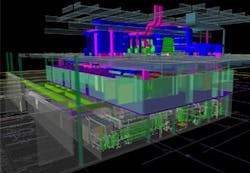

3-D modeling was another key to success. Early on, Biokinetics had created preliminary designs of the building’s piping system, and AES had performed concept development of the clean space. When the project become official, Biokinetics took all of the design documentation and modeled the entire BPDF facility inside and out.

3-D modeling guided the design and construction of the BPDF—shown here, the entire facility including the basement clean utility area, first level cleanroom space, and upper level mechanical support mezzanine.

Modeling meant that major wrinkles could be ironed out well before construction began. A case in point was the utility panel design, which required Biokinetics, with help from Central States Industrial Equipment and Service (Springfield, Mo.), to brainstorm how to transition process utility piping into the cleanroom environment by integrating utility stations into the wall system. Still, there are always issues that will arise in the field. Even with the entire piping system modeled, on-site engineers had to, for instance, figure out how to get a weld head on a WFI pipe with just six inches to work with. It wasn’t easy, says Leo Krieg, VP for Project Management. “Limited space was a general theme for the whole process,” he says.

Back to School

AES and Biokinetics each had limited project experience in academia, and they both learned that such projects are not without their peculiar challenges. For one thing, administrators are not schooled in the ways of GMP. “The university, outside of the BPDF, had no basis for what GMP meant,” says Jennifer LoMonaco, Project Engineer for Biokinetics. “It was a constant educational process on all sides.”

Othmer Hall is home to a variety of scientific research labs, significant in their own right, that needed to remain operational and undisturbed by noise and vibration during the BPDF redevelopment. Universities also have their bureaucracies and regulations that must be met.

For example, the BPDF needed its own exhaust systems, but because of university architectural restrictions the main exhaust equipment could not be placed on the building’s roof. Once a suitable location was found, double-wall ductwork was routed through two stories of the existing facilities. Not only did UNL’s architectural review board need to sign off on this and all other aspects of the project, but the university’s own design and construction teams had to be consulted as well.

Some of the host building’s utilities were insufficient to meet the demands of the BPDF. Questions about chilled water purity and capacity meant that a dedicated chiller had to be located outside Othmer Hall to serve the process needs of the facility. “Here was another piece of equipment that had to go outdoors and be fully reviewed by the university,” says Kevin Koffke, Director of Engineering for AES.

In the end, this academic project was a valuable lesson for all involved. “We had to learn how to play in the university’s backyard,” says Koffke of AES.

Was it worth the effort? “It was a great opportunity for us to build something new,” says Biokinetics’ Krieg.

It’s a great showcase of the entire team’s talents, says Merrill. “If you walked into the facility from off the street, you’d think it was in the private sector,” he says.

That’s the whole idea, says Meagher. “We had to get over the stigma that we’re a university,” he says. “I wanted to make sure that this was legitimate in the eyes of industry where they’d say, ‘Oh my gosh. Yeah, this is real.’ ”

It’s real, but the problem with Meagher’s dream home is that it’s not the kind of place where he can put his feet up on the couch and relax. The work begins now, lining up clients to take up residence once commissioning and validation are completed next summer.

|

Bells and Whistles Any new GMP facility must have its share of state-of-the-art characteristics. Following are a few of the bells and whistles installed at the BPDF:

The same control system is used in the fermentation development laboratory, with the same mass spec, making for seamless transfer of the fermentation process into the cGMP facility. This system can accommodate research into advanced process control, monitoring, and modeling, but is simplified for transfer of the process into a cGMP environment. Using Microsoft SQL Server, it is designed to take early-stage algorithms and lock them in throughout scale-up. “We’re eliminating as many hurdles for tech transfer as we can,” Meagher says. “The equipment that we use for scaling up is the exact same equipment that we have in our cGMP suite. Exact same chromatography skid. Exact same membrane processing equipment. Same fermentors and control systems and same type of homogenizers.” |