The issue of how to classify and regulate follow-on biologics is a tug of war and the stakes are high for all concerned: politicos, pharma companies and the public. One side argues for dramatic savings in both the staggering cost of and time-to-market for desperately needed biotherapeutics. The other side raises worrisome concerns over the safety and efficacy of products that could come to market without being subject to rigorous process scrutiny or clinical evaluation.

Senators Hillary Clinton (D.-N.Y.), Charles Schumer (D.-N.Y.), David Vitter (R-La.) and Susan M. Collins (R-Maine) and Representatives Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) and Jo Ann Emerson (R-Mo.) took the debate to a new level on Feb. 14 by introducing the “Access to Life-Saving Medicine Act of 2007” in their respective houses of Congress. The next day, bolstering the bill’s pro-biosimilars position, pharmacy benefits management firm Express Scripts issued a report claiming that generic biotech medicines could save U.S. health plan sponsors and patients $71 billion over 10 years.

The Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions further turned up the heat on Mar. 8 by holding a hearing on the subject. In addition to senators on that committee, speakers included:

- Sid Banwart, vice president of human services, Caterpillar;

- Dr. Jay Siegel, president of biotechnology R&D at Johnson &Johnson and a 20-year veteran of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research;

- Nicolas Rossignol, administrator of the European Commission Pharmaceuticals Unit;

- Dr. Ajaz Hussain, vice president of development at Sandoz and former deputy director of the Office of Pharmaceutical Sciences in FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

Each speaker represented a slightly different perspective. Banwart, speaking for Caterpillar and, unofficially, thousands of other U.S. corporate human resource directors, remarked, “As you know, the escalation of health care costs is a top concern for U.S. business executives... Last year alone, [Caterpillar] spent more than $600 million in the U.S. for comprehensive medical, dental, vision and prescription benefits.”

He urged Congress to “create an appropriate regulatory route for FDA review of biogenerics” and “grant the FDA the authority to use its discretion and scientific expertise to evaluate interchangeable and comparable biogeneric products while ensuring patient safety.”

To anyone unfamiliar with the drug industry or the workings of the FDA, Banwart’s plea would likely sound quite reasonable. However, when perceived through the filter of expertise in life sciences or regulatory affairs, Banwart’s choice of words could be rather polarizing. The problem is a matter of semantics, but it is far from academic, because the specific words that end up being written into bills that become law or guidance that becomes regulation concerning follow-on biologics will affect how such products may be produced, marketed and prescribed.

For example, whereas Banwart referred to “biogeneric products,” Dr. Siegel stressed that it would be inappropriate to view follow-on biologics in the same light as generic versions of chemical drugs. “There cannot be allowance for determinations of ‘comparability’ for products that are so different in structure that they should be considered different products entirely,” he stated, adding that “a follow-on biologic product should not be considered ‘interchangeable’ with its reference product.”

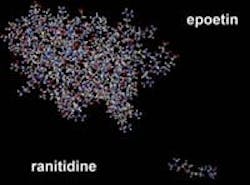

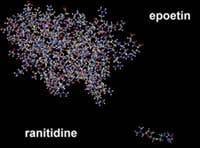

Whereas one can reverse-engineer a chemical drug, most biotherapeutics are logarithmically more complex in structure and effect.

This slide demonstrates the complexity of a biologic (epoetin) versus a small molecule drug (ranitidine). Courtesy of the Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO).

Siegel emphasized this by referring to an FDA letter written last September to the World Health Organization, to wit: “Different large protein products with similar molecular composition may behave differently in people and substitution of one for another may result in serious health outcomes, e.g., generation of a pathologic immune response.”

In his testimony, Rossignol described how the European Union (EU) has addressed all these issues. His agency set forth a framework that is both open and limiting, with broad parameters that are applicable throughout the EU, but specific details may be applied and enforced by each member state individually. The European Medicines Agency (EMEA) then issued guidance based on that framework. Rossignol explained, “…the licensing route for biosimilars is based on the principles that 1) biologics are not chemical drugs; and 2) the generic approach is, in the quasi-totality of cases today, very unlikely to be applicable to biologics: biosimilars are not ‘biogenerics’.”

Further, he said, “The EMEA guidelines make it clear that it is not expected that the quality attributes (e.g. the molecular structure) in the biosimilar and the reference product should be identical. Actually, minor structural differences are reasonably expected given the very nature of biologics and the inherent variability in the way they are produced. However, those differences should in any event be justified on scientific grounds and would be considered on a case-by-case basis, in relation to their potential impact on safety and efficacy. The underlying scientific assumption is that differences between the biosimilar and the reference product are, a priori, regarded as having a potential impact on the safety/efficacy profile of the product. They will therefore influence the type and amount of data required by the regulators in order to make a satisfactory judgment of compliance with EU standards.”

The result of this approach is that so far, only relatively simple biosimilars have been approved: the growth hormones Omnitrope and Valtropin (both were authorized in April 2006). There are others applications in the approval pipeline, though, including erythropoietins (EPOs), interferons, insulins and granulocyte-colony stimulating factors (G-CSFs). “An early dialogue between the manufacturers, the EMEA and the European Commission has proven critical to sort out the various regulatory and scientific issues that applicants may face,” Rossignol observed.

Dr. Hussain led off by pointing out that his parent company, Novartis, manufactures both branded and follow-on versions of chemical and biological drugs, yet most of his presentation supported a broader approach than Rossignol’s. He opined that while the EU approaches to biosimilars “suit an EU environment of 27 distinct countries with different legislative and regulatory histories as well as very different health care and reimbursement systems … the U.S. needs a solution that suits U.S. needs and statutory environment.”

He went on to say that, “…just as we trust the FDA to assess the unknown (new) biologic about which we necessarily have the least experience (namely the innovator products), using these criteria, so too can we entrust the Agency to evaluate follow-on biologics which refer to products for which we now have decades of experience.” Novartis executives believe that Congress should give FDA the flexibility to accommodate progress in science, and help enable the regulatory requirements to evolve appropriately.

Dr. Hussain asserted, “FDA can, through public notice-and-comment rulemaking, and guidance as appropriate, implement a comparability-based pathway for follow-on biologics without requiring arbitrary, unnecessary or unethical duplication of pre-approval studies or clinical trials, and by allowing appropriate extrapolation between indications based on mechanism of action.”

The FDA is, for the most part, keeping mum until the dust settles; a spokesperson said the Agency has not yet developed guidance and until it does, officials will not comment. However, on Mar. 15, FDA Administrator Andrew von Eschenbach told attendees of the annual meeting of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association (PhRMA) that the Agency will consider follow-on biologics only “similar” to innovators’ products, not interchangeable or able to be substituted, the Associated Press reported. Eschenbach added, “We recognize that the end point would be what could be best described as similarity… in the sense that when a doctor gives… the product… to a patient, it will achieve an effect that is similar to the effect that we expected from the innovative ... compound.”

Following Up on Follow-On BiologicsEditor's Note: Since we went to press with this article, debate, discussion and coverage in the popular press have continued at a lively pace. Here we provide links to additional information.

|